ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Viola König

Taking the important and extensive Mesoamerican collection of the Ethnologisches Museum (Ethnological Museum) in Berlin as an example, the following article explores the background and motivation for purchases of collections on the art market in the twentieth century. Among the entire holdings of the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin (EM) – founded in 1873 as the Königliches Museum für Völkerkunde (Royal Museum for Ethnology) – almost 200,000 objects from pre-Columbian America account for nearly two thirds. Accordingly, the collection’s provenance is heterogeneous. Until World War II, they were mostly the result of collecting trips, expeditions and field research organized by the museum itself. More recently, a group of objects considered to be problematic from today’s perspective was purchased from the art trade, with provenance histories in Mexico and Central America that are no longer traceable. Following the significant losses sustained in two world wars, the museum pursued a new acquisition policy. Closing gaps through the international art trade and, as we now know, also from dubious illegal sources was commonplace, for example in the Berlin Museum für Asiatische Kunst and the Antikensammlung.

Taking the important and extensive Mesoamerican collection of the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin as an example, the following article explores the background and motivation for purchases of collections on the art market in the twentieth century.

Among the entire holdings of the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin (EM) – founded in 1873 as the Königliches Museum für Völkerkunde (Royal Museum for Ethnology) – almost 200,000 objects from pre-Columbian America account for nearly two thirds. Accordingly, the collection’s provenance is heterogeneous. Until World War II, they were mostly the result of collecting trips, expeditions and field research organized by the museum itself. Among these, 13,000 objects alone were acquired from the couple Eduard and Caecilie Seler Sachs. In addition, there were donations, bequests, and sales from private individuals.

Among those objects with a problematic provenance are those which have the appearance of pre-Spanish originals yet were only made in the twentieth century. The earliest verifiable forgeries came from the Seler collection. Notably, until 1900 the Selers solely collected originals, and it was only during their final voyages to Mexico in 1907 and 1922 that the fakes they apparently did not recognize as such were offered to them. Among a total of 163 Zapotec funerary urns, the couple acquired fifty-four from Constantine Rickards, the former British Consul on Oaxaca who was himself directly involved in the process of making forgeries.1

The practice of exchanging so-called “doublets” was customary in the foundation period of ethnological museums.2 Museum directors and curators aimed to have overviews of material cultures in their possession which were to be as complete as possible. Exchanges with the art trade are considered especially problematic. While there was only a single such case in the Mesoamerica department, dating from 1971, the recorded exchange value was a significant sum of twenty thousand Deutschmarks (DEM).3 It is not clear whether the exchange value was set by the museum or by the dealer Emile Deletaille in Brussels. The museum relinquished a “Stone sculpture of a Standing Man” from Ecuador and an Aztec “Stone sculpture of a Standing Female Deity” in exchange for twelve wooden objects from Tehuacán, Puebla, with turquoise inlays (fig. 1).4

Fig.1: Wood with Mosaic Traces, 18,4 x 9,5 x 2,2 cm, Mexico Central Highlands Tehuacan IV Ca 46941. Exchange 1971.

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum / Claudia Obrocki.

A further group of objects considered to be problematic from today’s perspective was purchased from the art trade, with provenance histories in Mexico and Central America that are no longer traceable. Following the significant losses sustained in two world wars, the museum pursued a new acquisition policy. While the losses of the department of American archaeology were low in numbers – fewer than one hundred and fifty out of 200,000 – the gaps consisted of top items.5 Therefore, the years of economic upturn in the German Federal Republic from the late 1960s were used for targeted acquisitions from the art trade with view to compensating for the losses before 1945. Seventy-seven purchases from the art trade may only represent 0,15 percent of the entire holdings of around 50,000 objects in the Mesoamerican collections, yet these are problematic with regard to their provenance histories as well as acquisition methodology and ethics: “The criminal energy inverted by some of the art dealers and the willingness of collectors and museums curators to ignore suspicions in favor of unique artwork for their collections is a field highly worthy of our attention”.6

It is striking that these purchasing efforts were pursued most actively during the 1970s, that is in the wake of the 1970 UNESCO “Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property”. While other ethnological museums adhered to the convention, such as the institutions in Hamburg and Bremen, those responsible in the former Museum für Völkerkunde seem to have doubled down on their acquisition efforts.7 At that time, pre-Columbian art was not only offered in continental Europe but above all in the US. Dubious provenance histories, most likely from illegal excavations, bothered neither the dealers nor the Berlin Ethnologisches Museum, which bought directly from the trade until 1982. From the 1990s onwards, the museum no longer undertook acquisitions directly from the art trade but it now accepted donations from private collections which had been sourced from the trade.

Those seventy-seven items inventoried between 1969 and 2008 as “Archaeological Acquisitions” with inconclusive provenance histories were classified by the museum itself as “problematical” in a 2014 survey for the director general of the Staatliche Museen zu (Berlin state museums). Of these, about half are donations.

As was customary at the time, the art trade only supplied cursory information about the exact provenance of sold works.

The majority of objects purchased by the museum from the art trade came from Stolper Galleries with offices in New York, London, and Munich. Out of a total of twenty-six listings, three were marked as donations. The most expensive object bought from Stolper Galleries New York was a stucco vase from Mexico (IV CA 46181). On 1 May 1970 it was sold to the Berlin Ethnologisches Museum for 18,183 DEM (fig. 2). Three months earlier, Stolper had sold a jade chest plate from Costa Rica (IV Ca 46180) to the museum on 1 February 1970, for a not inconsiderable sum of 16,365 DEM.

A further five purchases for five-digit sums were made from Stolper in New York, London, and Munich. The remaining objects were bought for four-digit sums. Robert L Stolper is certainly familiar as a supplier for the Ethnologisches Museum:

From Stolper the Museum für Völkerkunde bought 279 ethnographic objects from different parts of the world: Africa, India, south East Asia and Australia; over half —195 objects— originate from the Americas Between 1960 and 1983, 79 pre-Columbian pieces were bought for the sum of 423.245 DM, with several acquisitions every year. A ceremonial knife (tumi) from Lambayeque (Peru) was bought from the Stolper Gallery in 1966 for the amount of 54.000 DM.8

Fig. 2: Stucco Vase Al fresco painting of underwater scene, late classic period, clay, painted al fresco; coiling technique, 15,9 x 10,3 x 10,3 cm, 2 kg, Mexico, Maya south Chiapas. IV Ca 46181. Purchase in 1970.

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum / Claudia Obrocki.

Stolper’s selling methods in Berlin are documented and published, including the sale of forgeries which he sold, among others, to the Berlin museum, such as a supposed stucco head from Palenque.9

A total of ten objects were purchased in 1970 and 1978 from the New York dealer Alphonse Jax, mostly polychrome vessels with reliefs from the Maya culture, for the total sum of 70,000 DEM. Jax was well known in north and central America. His sales and donations can be found in numerous north American museums. Using a pseudonym (“George Alpha”), Jax was consulted, among others, to evaluate the Grolier Codex.10 In Berlin his circuit included regular courtesy visits to the relevant curator Dieter Eisleb until the latter retired in 1991.

Apart from the abovementioned exchange, the museum bought a Huaxtec ball player and a Nayarit figure for 6,000 DEM, as well as three Coclé-style clay figures from Panama from the Brussels art dealer Emile Deletaille in 1972.

In 1982, the museum bought twelve clay vessels from El Salvador for 20,000 DEM, attributed to the Mayan culture, from the collector José Tienda Alba.

In 1995 the museum bought the so-called “Transfiguration-Tripod” (IV Ca 49845) from Marianne Huber for 200,000 USD. She and her husband Robert from Dixon, Illinois had acquired their Mesoamerican collection prior to 1970. They had lived in Mexico in the 1960ies.

In 1999 the museum acquired the polychrome “war scene vase” (IV Ca 50112) from Edwin Merrin for 325,000 USD. It is one of a group of six vases called the “Fenton School” whose provenance can be traced back in the US before 1970.

In the 1990s, the museum was willing to pay more than half a million USD for two Mayan vessels that were proven to have been outside Guatemala before 1970.

The collection which is arguably the most problematic and at the same time most outstanding in scholarly, artistic, and financial terms is a donation from the collector couple Claus Pelling and Marie-Luise Zarnitz. It comprises twenty-eight listings of purchases from the art trade and at auction which were donated to the Berlin museum from 1994 to 2008. 11 All pieces can be attributed to the Maya culture. Three come from Mexico, the remainder from Guatemala. The collector couple, who stated having bought these over more than thirty years, also had other collecting interests. On the website of the foundation they set up in 2017 in their residential town of Tübingen, their collecting focus is outlined as follows:

Both founders, Dr. Marie Luise Zarnitz and Dr. Claus Pelling regarded as their main objective to close what they felt were the most painful gaps – often also as a result of warfare – in German public collections, in particular in the areas of Maya artefacts, Byzantine lead seals, Early Egyptian artefacts, and Islamic numismatics, ideally with top pieces in order to make them accessible to an educated public. Even before setting up the foundation, [the founders] made substantial donations, first of all of Maya artefacts to the Ethnological Museum of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz Berlin (...).12

The donation came with conditions set up in a notarized contract dated 12 December 1994. It remained valid until the final donation in 2008. In the document, the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin committed not to relinquish the donations in their possession, to present them as part of the Maya display in the Ethnologisches Museum, and to label them as a donation with the information “Gift from Dr Claus Pelling and Dr Marie Luise Zarnitz”.

These commitments recently informed the exhibition display of the Ethnologisches Museum in the new Humboldt Forum in the centre of Berlin. Even though the museum had repeatedly pointed out to the collectors that the acquisitions from the art trade were problematic from today’s perspective, as implicitly resulting from illegal excavations and illegal export from countries of origin, the donors insisted on labelling in accordance with contractual obligations also in the Humboldt Forum (fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Showcases in the Humboldt Forum Berlin with the presentation of the Pelling and Zarnitz collection, 2022. © Viola König

Furthermore, the collectors and the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin had a binding agreement on a scholarly publication of the works which required consent from the donors with regard to authors, co-authors, concept, as well as place of publication. Such an agreement was also not without its difficulties. It followed the example of publications of US private collections which involved well-known scholars, a practice considered not entirely acceptable even in the 1980s. Authors were accused of indirectly sanctioning the illegal import of objects from illegal excavations.13

The publication by the two authors Maria Gaida and Nikolai Grube appeared in 2006.14 In his review, the Maya specialist Berthold Riese praised the volume “due to the exquisite pieces which are published here, some for the first time, and the scholarly sound descriptions and introductions to the Maya art of pottery”. However, he also criticizes:

This overwhelming origin of the collection in the art trade raises issues which cannot be addressed in the catalogue, for understandable reasons. Nearly all ceramics come from illegal and destructive excavations and entered the art trade in violation of national and international laws, from where they found their way directly or indirectly to the Berlin museum. 15

Both in legal and scholarly terms, the provenance is an issue, since a German museum becomes guilty of receiving stolen goods when purchasing such objects as well as accepting them as donations. Missing information about places and context of origin impedes scholarly research. Riese rightly criticizes the fact that not even available data about tracing previous owners, or previous publications, had been disclosed on the art market.16 This information is documented in the appendix, as far as it could be researched by the museum.

From 2001 at the latest, the museum pointed out to the collecting couple the necessity of providing documentation before every further donation that the objects in question had left their countries of origin before 1970, in line with the UNESCO convention.

Unfortunately, a requirement for documentation as a condition for accepting such donations was missing from the contract of 1994. The collectors, who had become aware of the increasingly critical position of the museum directors and the relevant curator since the 2000s, continued to nurture their close relationship with the director general of the museum’s umbrella organisation, which is reflected in a preface and an expression of gratitude from the director general in the catalogue as well as visits by his deputy in Tübingen.

The information about the objects’ provenance in correspondence and in the inventory books is sparse, consisting of brief descriptions of the objects, presumed geographical origin, mentions or illustrations in literature, or references for comparative pieces. However, they only refer back as far as the last dealer or auction where the objects were bought, and previous owners in the US where applicable.

While more detailed information had been provided for the first donations, it became increasingly meagre over time. Only references to “the art trade” remained. Was there no more information or was this done as a precaution?

There are only seven instances of references to previous owners. They are well known in museums and auction houses in North America and are listed in publications such as Sotheby’s catalogues of “Pre-Columbian Art”. But even though there is evidence in some cases that the works were exported to the US before 1970, an illegal and undocumented extraction from their original archaeological context is virtually certain.

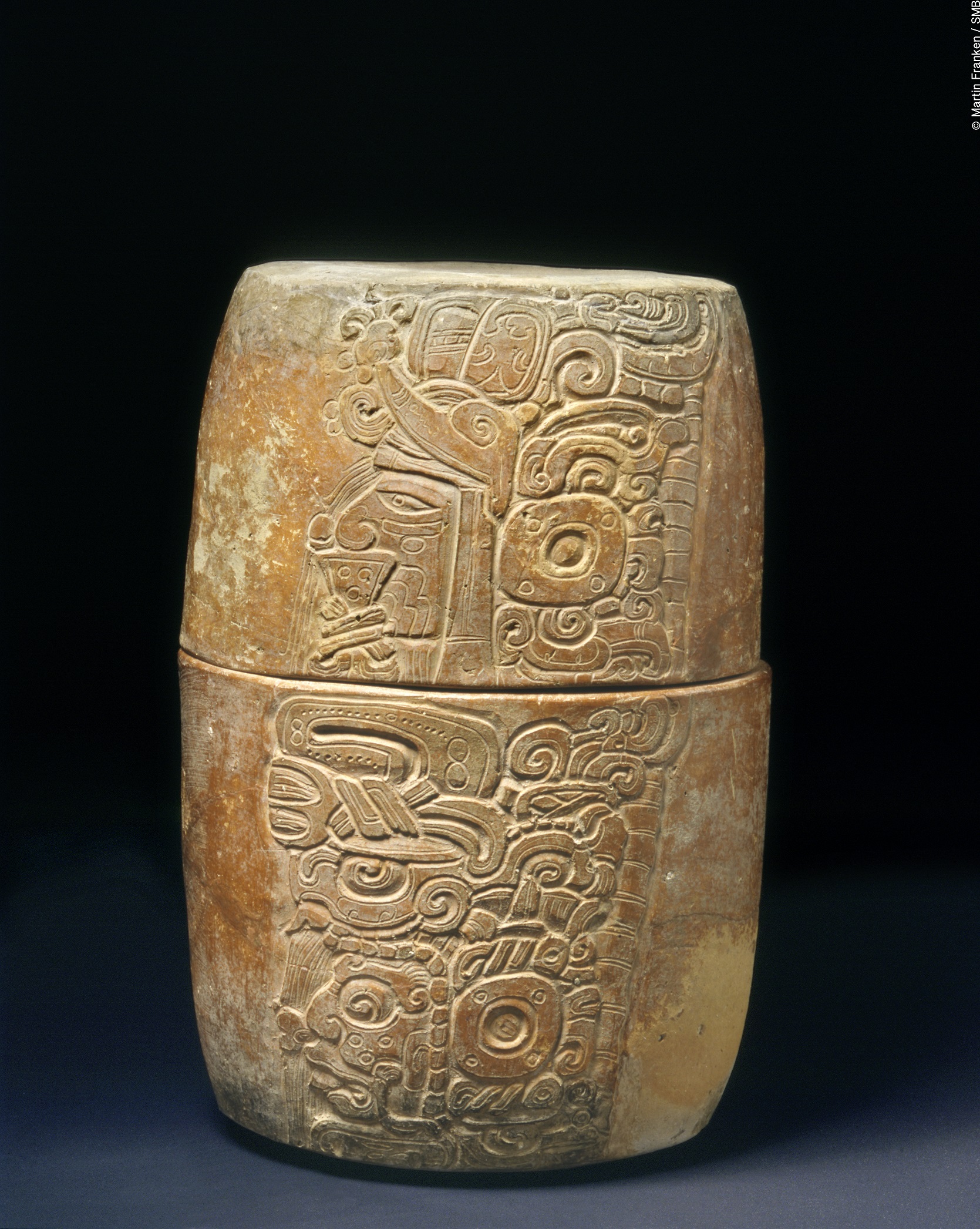

Gift no.1 from 1994 was a Cache Vessel (IV Ca 49842 a, b.) bought at Sotheby´s sale in New York on 19 November 1990 as lot 86 (fig. 4). Provenance: “Ex Wray Collection, Ex Manoogian Collections. Sotheby´s Auction, New York, 20 May 1986, lot 108”.

The New York Times reported on Peter G. Wray, a businessman residing in Scottsdale, Arizona:

(...) a major rancher who raises cattle and is in agriculture, with large land holdings in Arizona and New Mexico, assembled his collection of thousands of such art works in the late 1960’s and 70’s. He is selling, he said, to cover losses in his agricultural business. The art works offered range from $12,000 for two different Mayan polychromed ceramic plates, one showing a monkey deity and the other a dancer, to $500,000, the price asked for a three-foot-long Mayan stone panel, an intricately carved relief depicting two seated rulers and a glyphic text.

The collection is wide-ranging, revealing the unusual breadth of Mr. Wray’s interests. There are, for example, several memorable examples of Olmec material, completed before 900 B.C. - a haunting mask of a sensuous, brooding face chiseled of gray- green jade, and a burnished black ceramic bottle incised with a double- headed monster. From the same period comes a powerful ceramic figure of a standing youth.17

Notwithstanding this assessment, Donna Yates wrote about a different piece from the Wray collection, the Río Azul Vase now in the Detroit Institute of Arts:

Fig. 4: Cache Vessel, clay with relief, ealy classic period, 36,3 x 25 x 25 cm, 5 kg, Guatemala, Maya. IV Ca 49842 a,b, donation in 1994.

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum / Martin Franken.

Based on linguistic and stylistic evidence, this cylindrical blackware Maya vessel is thought to have been looted from the site of Río Azul in Guatemala. (...) The vase is thought to come from Tomb 12 at Río Azul as both the vase and the tomb bear inscriptions mentioning a person named Six Sky (Adams 1999: 93). This tomb is thought to have been opened by looters in the late 1970s as the building it was located in was recorded as intact by archaeologists before that time. The vase also bears the emblem glyph of Río Azul which very strongly links the vessel with that site (Adams 1999: 94).18

Yates quotes the officials she interviewed about their awareness of this problematic provenance in 1984, an outraged director and a scandalized curator. In Berlin, the provenance of the cache vessel from the “well known Wray collection” was not questioned.19

Gift no. 11 from 2003, a Dynastic Vase (IV Ca 50142), also came from the Wray Collection, but had been in the private collection of Francis Robicsek before, prior to the publication of his catalogue which is pointedly referenced by Pelling/Zarnitz (fig. 5).20 This publication was also criticized by specialists, based on similar arguments as quoted above.

Robicsek was Hungarian by birth and a renowned cardiologist. Travelling in central America to offer medical services, he began to visit Maya sites and became an amateur researcher collecting, among other objects, pre-Columbian art.21

Fig. 5: Dynastic Vase, clay vessel, clay, polychrome paint, hieroglyph inscriptions, late classic period, 11,7 x 13,8 x 13,8 cm, 0,4 kg, Guatemala, Maya. IV Ca 50142, donation in 2003.

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum / Claudia Obrocki.

Gift no. 3 in 1996, the “Enema Vase” (IV Ca 49923) was bought at auction with Sotheby’s New York in December 1987 (sale no. 5635) (fig. 6). It came from the multifaceted collection of Mr. and Mrs. Jay Whipple, Chicago.22 Nicholas Hellmuth referenced the vase even before its sale to the Berlin museum, but in connection with another vessel already purchased from Stolper Galleries on 5 October 1972:23 “The Whipple Vase and a vessel in a West Berlin museum each show the turban-bib held by a female attendant near the man who will be dressed.” (...) “On a vase in a West Berlin museum a woman (wearing clothing with a painted, tabbed “turtle carapace” symbol associated with enema attendants, see diagnostic Trait # 12) offers a bundle of sticks to a man”.24

To date, nothing is known about the provenance of the Enema Vase before it was purchased by Whipple.

Gift no. 6, the Jade Mask (IV Ca 50115) bought by Pelling and Zarnitz in 1988 and donated to the Berlin ethnological museum in 2000, came from the Wally and Brenda Zollman Collection of Precolumbian Art. The Zollmans had assembled the items from the early 1980s over a period of five years.

Fig. 6: Enema Vase, Cylindrical vessel with enema scene, clay vessel, polychrome paint, classic period, 24,2 x 18 x 18 cm, 1,3 kg, Guatemala, Maya, IV Ca 49923, donation in 1996.

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum / Martin Franken.

In 1988, Lee A. Parsons, John B. Carlson, and Peter David Joralemon published this collection with a “Foreword by Michael D. Coe”.25 The reviewer Margot Blum Schevill commented in a similarly ambivalent vein as Berthold Riese would do eighteen years later:

I must admit to a dualistic reaction to catalogues of recently acquired objects of antiquity from abroad. Questions arise concerning the involvement of pre-Columbian scholars who conduct research on unprovenanced collections of what must have been mostly sacred objects that were not excavated scientifically. Hence the cultural context in which they functioned is lost and must be inferred by comparison to better documented material. (...) several well-known scholars have contributed essays and information (...) in the present climate of repatriation of sacred objects to native peoples of North America, the acquisition of such a high quality collection in the brief period of five years appears to be anachronistic. Parsons, however, does not share my sentiments. He writes that the Zollman collection “demonstrates that great private pre-Columbian collections can still be created, despite current tight restrictions on the direct importation of such objects from their countries of origin” (p. xi). (...) Whether these graves were professionally excavated or looted (...) the prolific ceramics and other media provide an encyclopedia of ancient life for art historians (...). (p. 201)”. 26

Fig. 7: Clay figure, Figure of a dwarf with mirror in the hands, blue paint, late classic period, 15,6 x 8,1 x 6,8 cm, 0,32 kg, Mexico, IV Ca 50146, donation of 17 November 2004.

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum / Claudia Obrocki.

Gift no. 14, a clay figure “Dwarf Before a Mirror” (IV Ca 50146) was donated by Marie Luise Zarnitz to the Berlin Ethnologisches Museum on 17 November 2004, ten years after she bought it at a Sotheby’s sale in New York on 7 May 1994 (lot 107) from the estate of Mildred Friedland (fig. 7). Gift no. 15, a “Bowl with the Head of a Deity with Stag Ears” (IV Ca 50147) most likely came from the same collection. Marie Luise Zarnitz had acquired it at auction from Sotheby’s “following the death of a female collector”. Both objects are similar in style, execution, and colouring which suggests the same provenance.

Another piece from this batch is Gift no. 16 from November 2004, the Rio Blanco Vessel (IV Ca 50148), acquired by Claus Pelling from a “Washington collection, via von Winning as an intermediary, early 1990s, Mexico”. The specialist Hasso von Winning was himself a collector. He published several times on a group of ceramic objects with reliefs from the Rio Blanco and Papaloapan area in the Veracruz region and knew the provenance and whereabouts of numerous vessels in north American museums and above all private collections. In a publication he edited with Nelly Gutierrez Solanas, he listed sixty-five vessels.27 Emilie Carreón Blaine closed her review of the book with the sentence: “I only hope that the looting that has taken place in the Mixtequilla region will stop and that the other fifty vessels mentioned by the authors will be excavated under controlled conditions before they are found by looters and collectors”.28

Gift no. 23 from 6 July 2005 is the last example where the collector Zarnitz at least refers to the name of the previous owners (fig. 8). The stucco mask from Guatemala (IV Ca 50419) was acquired at Sotheby’s New York on 16 May 1995 as lot 176 from the “Collection of Precolumbian Art of Mr. und Mrs. Klaus G. Perls”. Klaus Perls was a descendant of a Jewish family of art dealers from Berlin and opened his own gallery in New York after leaving Germany in 1937. Here, Perls Galleries operated for sixty years and offered mainly pre-Columbian art.

Fig. 8: Stucco mask, Jaguar god of the underworld, late classic period, 17,1 x 14,5 x 9 cm, Guatemala, Maya, IV Ca 50419, donation 6 July 2005.

© Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum / Claudia Obrocki.

To summarise the findings of the Pelling and Zarnitz collection: the collectors were unable to provide the required documentation for any of the objects purchased from the 1980s onwards to confirm that they had been in the US before 1970. The allegation of illegal procurement by the previous owners, implicity read as a “misdemeanour”, lingers.

In 1973, the former curator Dieter Eisleb had made contradictory statements. On the one hand, he explained that

The author of this article then travelled to Mexico in 1966 as a participant in the German-Mexican Puebla-Tlaxcala project. Even though several excavations and investigations were conducted during these travels, they did however not yield any collections for the museum. The laws of the countries involved were a hindrance.

Nevertheless, he did not identify this problem with acquisitions from the art trade. On the contrary, his department had been

(...) therefore entirely reliant in its acquisitions of collection pieces since 1945 on the art market and on objects in European private collections. These acquisitions, which could not reach any great volume due to the enormous price increases of the last twenty years, were above all subject to two guiding principles: On the one hand compensation was sought for the war losses, and on the other hand, it was attempted to gradually fill gaps which had been present in the holdings from the outset”.29

The acquisitions from the 1970s did “compensate” for the war losses. The exchange with the art dealer Emile Deletaille seems to have been prompted by a desire to replace four early and valuable turquoise works which had been registered as lost after the war with twelve, albeit not very attractive fragments (fig. 1).30

The ambition to fill “gaps in the holdings” of a Mesoamerican collection consisting of nearly fifty thousand objects still reflected an earlier attitude from the foundation period of large museums in Europe and North America, when such institutions saw themselves in competition for the accumulation of objects. Even in the 1990s and early 2000s, collectors like Pelling and Zarnitz aspired to fill gaps in the holdings of a public museum by means of private purchases from the art trade. Their plans fell on sympathetic ears at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, whose collections had suffered war losses that were in part considerable. Closing gaps through the international art trade and, as we now know, also from dubious illegal sources was commonplace, for example in the Berlin Museums für Asiatische Kunst and the Antikensammlung.

As I demonstrated in this article, the provenance notes of the seventy-seven pre-Columbian works in Berlin’s Ethnologisches Museum ended with the previous owners in the US. At this juncture, the Berlin collection enters the expansive and long-term project “Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past”, the title of the eponymous anthology published already thirty years ago.31 In his review, Benjamin Keen mostly quoted critical perspectives on the project, which

steadily and surely guided the transfer of Pre-Columbian artifacts - as aesthetic objects, as scientific data, and as symbolic capital - into the public museums and private galleries of metropolitan North America and Europe” (Curtis M. Hinsley32).

(...) being collected, appropriated and transformed with little if any attempt to understand them “on their own terms” (Holly Barnet-Sanchez33).

(...) an economic system, divided into realms of production, distribution, and consumption” (Michael Coe34).

Keen himself arrives at the overall conclusion: “Inevitably, the system had its seamy side, involving not only fakes and forgeries but violations of the laws of the “donor” countries and a general indifference to the implications of this cavalier “appropriation” of the cultural heritage of those countries”.35

The publication date of these quotes was 1994, the time when Pelling and Zarnitz began with their donations to the Berlin Ethnologisches Museum and set up the contract for further gifts.

By now, the situation has changed. It is becoming increasingly difficult for the art trade, collectors, and their heirs to sell pieces from undocumented sources, as recent cases from Asia and Africa confirm. The position of potential buyers has changed after all, no one wants to buy works with problematic histories, become involved in legal disputes, or be subject to negative publicity. The expert Patty Gerstenblith is therefore convinced “that once something is out there, it can influence the market.”36

The Berlin Ethnologisches Museum has closed the chapter on acquisitions from the art market anyway. But the problems and the allegation of receiving stolen goods persist. Should future provenance research on the collections of the previous owners in the US and their intermediaries result in concrete findings about the works’ origin, and should the source even be proven to be an illegal excavation and illegal export, the consequence would be requests for restitution. In that instance, even the notarized contract of 12 December 1994, which commits the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin not to relinquish ownership of the donations, would no longer stand in the way.

Viola König is an honorary professor at Freie Universität Berlin. She was the director of the Ethnological Museum of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin from 2001 to 2017.

Translation: Susanne Meyer-Abich

1) IV Ca 49842 a, b. 1B/94/7. 1994.

Cache Vessel, Maya Early Classic period, clay, carved, Guatemala.

Claus Pelling, Sotheby´s sale, New York, 19 November 1990, lot 86, ex Wray Collection, ex Manoogian Collection. Sotheby´s sale, New York, 20 May 1986, lot 108.

Wray collection assembled in the late 1960s/70s.

2) IV Ca 49843. 1B/95/1. 1995.

Small Cormoran Vase, Maya Classic period, clay, polychrome paint, Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, from the New York antiquities trade, 1980s.

3) IV Ca 49923. 1B/96/4. 1996.

Enema Vase, clay, polychrome paint, Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, Sotheby´s New York (sale 5635, Dec.1987) from the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Jay Whipple, Chicago.

4) IV Ca 49928. 1B/97/1. 1997.

Cocoa Bowl, carved, Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, Sotheby´s, which sale?

5) IV Ca 50113. 1B/99/7. 1999.

Vessel with Relief, clay, carved. Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, purchase 1973/74, Galerie Gerdes, Munich.

6) IV Ca 50115. 1B/2000/1. 2000.

Jade Mask, Jade. Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, The Wally and Brenda Zollman Collection of Precolumbian Art, 1988.

7) IV Ca 50116. 1B/2000/2. 2000.

Itzamnaj Vessel, clay, polychrome paint. Guatemala.

Claus Pelling, formerly in an Italian Veracruz collection.

8) IV Ca 50119. 20001B/2000/8. 2000.

Plate in Codex Style, clay, polychrome paint. Guatemala.

Claus Pelling, Belgian art trade, later German art trade.

9) IV Ca 50139. 1B/2002/1. 2002.

Ink Bottle, clay, carved. Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, Sotheby´s, which sale?

10) IV Ca 50140 1B/2002/3. 2002.

Jade Pendant, Jade. Guatemala.

Claus Pelling, art trade.

11) IV Ca 50142. 1B/2003/1. 2003.

Dynastic Vase, clay, polychrome paint. Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, previous owner: Robicsek private collection, (prior to the publication in 1981). Later Wray Collection.

12) IV Ca 50143. 1B/2003/2. 2003.

Uaxactun Bowl, clay, polychrome paint. Guatemala.

Claus Pelling, similar vessels entered the US around 1970.

13) IV Ca 50145. 39/2004/AMA. 2004.

Stone Vessel with Reclining Figure, stone, carved. Guatemala.

Claus Pelling, Sotheby´s New York, 16 May 1995, lot 136.

14) IV Ca 50146. 38/2004/AMA. 2004.

Clay Figure (Dwarf), clay, Mexico.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, Sotheby´s New York, 7 May 1994, lot 107 (Estate of Mildred Friedland).

15) IV Ca 50147. 38/2004/AMA. 2004.

Bowl with the Head of a Deity with Stag Ears, clay. Mexico.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, Sothebys, sold at auction following the death of a female collector.

16) IV Ca 50148. 39/2004/AMA. 2004.

Rio Blanco Vessel, clay, carved. Mexico.

Claus Pelling, from a Washington collection via the intermediary (Hasso von) Winnings, early 1990s.

17) IV Ca 50149. 42/2004/AMA. 2004.

Stone Torso, stone, carved. Guatemala

Marie Luise Zarnitz, allegedly offered on the market for decades before being purchased in the early 1990s.

18) IV Ca 50169. 11/2005/AMA. 2005.

Vessel with Cocoa and Monkey Images, clay, carved. Guatemala.

Claus Pelling purchased via Huber at the beginning of the 1990s.

19) IV Ca 50170. 10/2005/AMA. 2005.

Stone Plaque with Hieroglyphs, greenstone. Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, purchased from the art trade in the early 1990s.

20) IV Ca 50171. 10/2005/AMA. 2005.

Vessel with Serpent Relief, clay, carved. Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz. Art trade.

21) IV Ca 50171. 10/2005/AMA. 2005.

Shell Plaque, shell. Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz. Art trade.

22) IV Ca 50418. 16/2005/AMA. 2005.

Vase with the God of Death, clay, polychrome paint. Guatemala.

Claus Pelling. Art trade.

23) IV Ca 50419.17/2005/AMA. 2005.

Stucco Mask, stucco. Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, Sotheby´s New York, 16 May 1995, lot 176 from the Mr. and Mrs. Klaus G. Perls Collection of Precolumbian Art.

24) IV Ca 50420. 17/2005/AMA. 2005.

Zacualpa Vessel, clay, carved. Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, art trade.

25) IV Ca 50468. 7/2006/AMA. 2006.

Shell Fragment with Hieroglyphs, shell. Guatemala

Marie Luise Zarnitz, art trade.

26) IV Ca 50512. 24/2007/AMA. 2007.

Bowl with Hieroglyphs, clay, polychrome paint. Guatemala

Claus Pelling, art trade.

27) IV Ca 50570. 19/2008/AMA. 2008.

Jade Pendant, jade. Guatemala.

Marie Luise Zarnitz, art trade.

28) V Ca Permanent loan by Pelling/Zarnitz. 2 a,b. 2006.

Rattle Handles, bone. Guatemala.

1 Carlos Morales Merino, Stefan Röhrs, Adam T. Sellen, Kay Sunahara, Robert Mason, Marie Gaida, and Ina Reiche, Linking HM 1953 to a Possible Companion Urn in Berlin, in Adam T Sellen ed., Real Fake. The Story of a Zapotec Urn (Royal Ontario Museum, 2018), 248-49.

2 Beatrix Hoffmann, From Museum Objects to Trading Goods: the Ethnographic Doublet, in Journal for Art Market Studies 1 (2022). Viola König, The Berlin Ethnologisches Museum. Its New Role as a Catalyst in the Humboldt Forum and the Implications for the German Restitution Debate, in Thomas Sandkühler / Angelika Epple / Jürgen Zimmerer, eds., Historical Culture by Restitution? A Debate on Art, Museums, and Justice (Köln, Weimar, Wien: Böhlau Verlag 2023), 312.

3 The DEM value equates to more than double in Euros i.e. 40,559.50 EUR resp. 42,685.34 USD.

4 Bastian (1878, V A 2191) and Seyffart (um 1850, IV Ca 173) collections, in exchange for Emile Deletaille collection (IV Ca 46935-46947). Detailed information on the Brussels Tehuacán collection cf. Martin E. Berger, “From a cave near Tehuacán”. An attempt to reassemble Post-Classic Mesoamerican ritual deposits that were separated by the art market, in Cara G.Tremain and Donna Yates, eds., The Market for Mesoamerica. Reflections on the Sale of Pre-Columbian Antiquities (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019), 112-135.

5 Dieter Eisleb, Abteilung Amerikanische Archäologie, in 100 Jahre Museum für Völkerkunde Berlin, Baessler -Archiv N.F. XXI (1973), 197.

6 Manuela Fischer, Stefan Röhrs, Elena Gómez-Sánchez, Regine-Ricarda Pausewein, Hermann Born, Ina Reiche and Kai Engelhardt, Product of the art market? The representation of silver corncobs at the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin, in bifea, 46 (1) (2017), 291-305, https://doi.org/10.4000/bifea.8301: 303.

7 Martin E. Berger, Between policy and practice - The impact of global decolonization on the National Museum of Ethnology, Leiden, 1960-1970, in MCS Yearbook (2021), 82.

8 Fischer et al., Product, 2017, 300f.

9 Martin E. Berger, Real, Fake or a Combination? Examining the Authenticity of a Mesoamerican Mosaic Skull, in Alexander Geurds & Laura, Van Broekhoven, eds., Creating Authenticity. Authentication Processes in Ethnographic Museums (Leiden: Sidestone Press, 2013), 11-37. Maria Gaida, Real or Fake? German Post-War Nationalism and the forged Maya Stucco Head in the Ethnologisches Museum, in Ixiptla (1, 2013), 77-89. Fischer et al., Product, 2017.

10 Also known as the Maya Codex of Mexico (MCM), the codex is a screenfold manuscript. Donna Yates, 2017, https://traffickingculture.org/encyclopedia/case-studies/mosaic-maya-mask/ .

11 Marie Luise Zarnitz died on 1 July 2020. Claus Pelling died on 25 May 2023. https://pelling-zarnitz-stiftung.de/?page_id=104.

12 https://pelling-zarnitz-stiftung.de/?page_id=82. Translated from German for this article.

13 On the debate cf. the documentary film by David Lebrun, Out of the Maya Tombs, 2014 (https://nightfirefilms.org/films/out-of-the-maya-tombs/).

14 Nikolai Grube and Maria Gaida, Die Maya: Schrift und Kunst (Berlin, Köln: SMB-Dumont, 2006).

15 Berthold Riese, Review “Die Maya. Schrift und Kunst” von Nikolai Grube/Marie Gaida, in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie (Bd. 132, H. 2, 2007), 318-320, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25843106). Quote translated for this article.

16 Riese, Review 2007.

17 Rita Reif, Antiques View, in The New York Times (8 April 1984).

18 Donna Yates, Río Azul, in Trafficking Culture (8 Aug 2012, https://traffickingculture.org/encyclopedia/case-studies/rio-azul-vase/).

19 Gaida und Grube, Die Maya, 2006, 16.

20 Francis Robicsek, The Maya Book of the Dead: The Ceramic Codex (Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Art Museum 1st edition, 1981).

21 Todd A. Herman, Dr Francis Robicsek, Pioneering Heart Surgeon. Art Collector & Renaissance Man, in Antiques and The Arts Weekly (28 April 2020), https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/dr-francis-robicsek-pioneering-heart-surgeon-art-collector-renaissance-man-94/. There is a surprising number of physicians among US collectors in this field.

22 Debbie Kane, Jay N. Whipple Jr., in Phillips Exeter Academy (2023), https://www.exeter.edu/people/jay-n-whipple-jr).

23 Strangely, the vase is not referenced in the Maya catalogue of 2006, even though it does appear on the museum website: IV Ca 46964, (https://smb.museum-digital.de/object/26838).

24 Nicholas M. Hellmuth, Principal Diagnostic Accessories of Maya Enema Scenes, 3rd revised edition, in Preliminary Notes in Maya Iconography: F.L.A.A.R. No. 5 (1985), 5-6.

25 Lee Allen Parsons, John B. Carlson and Peter David Joralemon, The Faces of Ancient America: The Wally and Brenda Zollman Collection of Precolumbian Art (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988).

26 Margot Blum Schevill, Review, in American Indian Quarterly (vol. 16, no. 4 1992), 557-559, https://doi.org/10.2307/1185312).

27 Hasso von Winning y Nelly Gutiérrez Solana, La iconografía de la cerámica de Río Blanco, Veracruz (Mexico: UNAM, 1996).

28 Translated for this article from the original: “Sólo espero que los saqueos que se han efectuado en la región de la Mixtequilla se detengan y que las otras 50 vasijas que los autores mencionan se excaven bajo condiciones controladas antes de que las encuentren los saqueadores y los coleccionistas.” Emilie Carreón Blaine, Reseña de “La iconografía de la cerámicade Río Blanco, Veracruz” de Hasso von Winning y Nelly Gutiérrez Solana, in Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas XIX (71) (1997), 89-95.

29 Translated from the German original for this article: “Der Verfasser dieses Artikels reiste dann 1966 im Rahmen des deutsch-mexikanischen Puebla-Tlaxcala-Projektes nach Mexico. Wurden auf diesen Reisen auch mehrere Grabungen und Untersuchungen durchgeführt, so fanden sie doch keinen Niederschlag in Form von Sammlungen für das Museum. Die Gesetze der entsprechenden Länder standen dem im Wege“. (...) „somit seit 1945 beim Erwerb von Sammlungsstücken ausschließlich auf den Kunstmarkt und auf den Ankauf von im europäischen Privatbesitz befindlichen Objekten angewiesen. Bei diesen Erwerbungen, die, bedingt durch die enormen Preissteigerungen der letzten zwanzig Jahre, keinen großen Umfang annehmen konnten, waren vor allem zwei Gesichtspunkte richtungweisend. Zum einen sollten die Kriegsverluste ausgeglichen werden, und zum anderen wurde versucht, Lücken, die schon immer in den Beständen vorhanden waren, nach und nach auszufüllen.“ Eisleb, Abteilung Amerikanische Archäologie, 1973, 183.

30 Viola König, Curious Things from Mexico in Early German Collections, 1525–1835, in Andrew D. Turner and Megan E. O’Neil, eds., Collecting Mesoamerican Art before 1940: A New World of Latin American Antiquities (2024), 43-49.

31 Elizabeth Hill Boone, ed., Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past (Washington, DC. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1994).

32 Curtis Hinsley, In Search of the New World Classical, in Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past (Washington, D.C. Dumbarton Oaks 1994), 105–122.

33 Holly Barnet-Sanchez, The Necessity of Pre-Columbian Art in the United States: Appropriations and Transformations of Heritage, 1933–1945, in Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past (Washington, D.C. Dumbarton Oaks 1994), 177–207.

34 Michael D Coe, From huaquero to connoisseur: the early market in pre-Columbian art, in Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past (Washington, D.C. Dumbarton Oaks 1994), 271-290.

35 Benjamin Keen, Review “Collecting the Pre-Columbian past” by Elizabeth Hill Boone, ed., in Ethnohistory, vol. 41, no. 3 (Duke University Press, 1994) 487-488.

36 Elyssa Cherney, A Rare Statue of Buddha Fails to Sell at Auction as Questions Swirl Around a Renowned Art Collection, in ProPublica (27 March 2023), https://www.propublica.org/article/rare-buddha-didnt-sell-questions-grow-around-alsdorf-art-collection-chicago.