ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Céline Brugeat

From New York to California and even some tropical islands, medieval architectural fragments or entire monuments were re-assembled and rebuilt by wealthy American collectors. If Alva Vanderbilt, Isabella S. Gardner or John P. Morgan were the first to introduce medieval art to United States collections, it was not until 1914 with the opening of the spectacular George Grey Barnard cloisters that the public could visit a place especially dedicated to French medieval architecture. The reconstruction of these remains reveals different practices of collecting and display but also raises questions about the reasons for such a massive hemorrhage of European architectural heritage. Most long-term properties of the French Church had already suffered from the ravages of the Hundred Years’ War as well as from the wars of Religion, from the gradual desertion of religious institutions by their communities during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and, finally, from vandalism and alienation of ecclesiastical properties during the French Revolution. However, during the post-revolutionary period until the early twentieth century, general indifference and negligence regarding the national heritage, abandoned to private hands, largely contributed to scattering this dismantled monumental patrimony across the country. In this tumultuous context, Paris became the central market for opportunist French dealers and their international clientele. Ambitious collectors and museums reassembled these spectacular ensembles in creative and reinvented structures.

“The authenticity of a section of the Bonnefont Abbey cloisters in Comminges, said to be part of the Cloisters museum in New York, is a cause for concern. It could be classed with the Marciac cloister, taken from Gers in the beginning of the 20th century. Some still believe that it could have been recreated, the original left abandoned by the port lost forever in the New York concrete (...). At that time, museums and wealthy Americans bought in droves the architectural heritage of Gascony.”1

This article from La Dépêche in 2003 reveals the French public opinion’s amazement regarding the translocation of this monumental heritage, so far from their own country. Following lectures, meetings and exchanges with many different actors, it seems necessary to finally revise the commonly held opinion that American antique dealers had “snatched” cloisters from their mother country. If such a market existed between France and the United States, it was with certain preconditions, requiring both the availability of abandoned architectural heritage and a taste for ruins and monumental sculpture, marketed as “La Vieille et vénérable pierre de France”.2

From the eleventh up to the fifteenth century, the religious world was redrawn by the growing stream of pilgrims on the Pyrenees roads towards Santiago de Compostela and by the successful establishment of monastic orders. These created a considerable body of architectural and artistic heritage in the region.

Fig. 1: Cloister of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, Haute-Garonne, France

Among the most emblematic examples of religious architecture of the period, the cloisters of the Midi-Pyrenées region truly stand out. Two styles collided in the twelfth century: the first features fantastic animals and human figures decorating the capitals of the cloisters of the abbey of Saint-Pierre de Moissac, of the cathedrals of Saint-Bertrand de Comminges (fig.1) or of the collegiate church of Saint-Gaudens; the second style, exemplified by the Cistercian abbeys such as Bonnefont or Escaladieu, presented a calming world of plant motifs and smooth foliage. This latter style influenced later orders, most notably those of the mendicant friars who moved to the region at the end of the thirteenth century.

Fig.2: Cloister of "Montréjeau", Paradise Island, Bahamas

The stylistic proximity sometimes causes confusion among antique dealers, collectors, as well as art historians tasked with identifying the origin of sculptures in collections in the United States. For example, the French cloister exhibited at The Cloisters in New York was attributed to the Cistercian abbey at Bonnefont-en-Comminges, but in fact principally originates from mendicant monasteries; conversely, the so-called “Augustins de Montréjeau” cloister erected in the gardens of a private property in the Bahamas (fig 2.) is to a large extent comprised of sculptures attributed to the Cistercian abbeys of Berdoues and Escaladieu. The blurred boundary between the two styles reveals and attests to the growing productivity of the period’s sculpture workshops.

The use of marble and marbled stones for capitals, columns and bases also contribute to the original style of the Midi cloisters. First adopted during antiquity and the Romanesque period, marble was widely used throughout the thirteenth century in the construction of cloisters in Cistercian and Benedictine abbeys, and also in cathedrals. At the end of this century, the mendicant friars commissioned the same workshops, who were already familiar with working the same type of marble, to create fashionable cloisters.

Similarly, at the end of the Medieval Ages, numerous monastic communities spread across the region in France, creating a closely-linked network. In the extensive south-west area there are at least 150 Benedictine, Cistercian, Fontevrist or Premonstratensian sites, out of over 190 mendicant monasteries,3 as well as around fifty canon communities. With only a few exceptions, all of them feature gorgeous marble cloisters.

Even today, it can prove difficult to determine the layout and architecture of cloisters which were ravaged by time and human violence. Even if natural events such as flooding or fires caused significant damage, armed conflicts were inevitably the most destructive.

Gascony was the scene for the tension and conflict erupting between those territories dominated by England and those loyal to the French crown. Communities were subject to pillage and destruction, and those built extra muros or in isolated areas were heavily targeted. For example, the Cistercian abbey at Flaran was partially destroyed during the Hundred Years’ War, losing its early gothic cloister.

However, it was the Religious wars that proved to be most devastating in this region. Entire communities were wiped out and monasteries razed to the ground. Protestant troops found an opportunity for lucrative commerce during a time of upheaval by selling the beautiful architectural fragments. The Franciscan cloisters at Morlàas and of Montauban were duly dismantled and sold to the highest bidder. To this day, parts of the cloisters can be found arching over doorways of town houses (fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Portal with colums from the couvent of the Franciscan monastery, Morlaàs, Pyrénées-Atlantiques, France

Once the friars could return to their dwellings, they launched reconstruction projects. However, the dimension of the task coupled with a lack of available resources meant that repairs only used more modest materials such as rubble and brick or re-used materials. As such, the abbey at Saint-Sever-de-Rustan bought sculptures from the partially destroyed Carmelite cloister at Trie-sur-Baïse to restore their galleries which had been ransacked by the Huguenot captain Lizier’s troops.

Furthermore, despite the restoration and construction campaigns, religious communities were weakened by the loss of landed property, by the vocation crisis, and by the loosening of the Rule, consequences which were due in part to the unstable in commendam system. The shrinking communities experienced a progressive degradation of their material holdings, resulting in the need to sell parts of their land, sometimes including their own enclosures, as was the case with the Franciscans of Tarbes. Indeed, just before the Revolution, a number of medieval cloisters had already disappeared or had been largely altered, leaving little of their former splendour.

Even though the religious institutions of the Midi were relatively spared from the vandalism of the Revolution, the sequestering and sale of national property intensified the transformation and destruction of this already diminished heritage. The abbey churches and monastery chapels were converted into parish churches and survived for the most part by being dismantled, but cloisters as well as other monastic buildings were sacrificed.

Municipalities often refrained from getting involved in the preservation of these monuments, and in certain cases, even abandoned or scattered them intentionally. In 1854, the Larreule city council unanimously decided to hand one of its citizens, the amateur archaeologist Gustave-Bascle de Lagrèze, the cloister’s west arcades, used as an enclosure for the cemetery.4 About ten years later, Louis Cartérot, the mayor of Larreule, and the city council sold a set of five sculpted stones from the cloister, considered to be “of no use for the city” to Emile Liau, an antiquarian in Tarbes.5 The plot thickens, as the same Louis Cartérot also acted as a middleman for the American sculptor George Grey Barnard, whom he considered a “dear friend”, and pledged to be “at his service”.6 Sometimes municipalities reused a few of the carved stones to embellish or strengthen the village church, either out of self-interest or in a feigned attempt at “conservation”; in the church at Saint-Laurent-sur-Save, the capitals of the former abbey support statues (fig.4).

Such public disengagement seemed legitimate at the time, seen in the context of the secularisation of society overall. Further strengthened by the 1905 law of the separation of the church and state, the French Republic supported an anti-clerical campaign through the radical socialists who were particularly present and active in the south-west of France. Furthermore, the destruction and reuse of cloisters formed part of the nineteenth century urban renewal process. Cities of all sizes razed their ramparts, mapped out new streets and used leftover ‘useless’ spaces to construct buildings for the growing urban population. In this way, the convent of the Carmelites of Toulouse was replaced by a market hall.

Fig. 4: Capital from the cloister of the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Laurent-sur-Save, Parish church, Saint-Laurent-sur-Save, Haute-Garonne, France

Left to the lay people, unconcerned by architectural coherence, the majority of religious architectural heritage sites were converted into workshops, shops, housing, warehouses or, most frequently, turned into reused material and quarries, such as the cistercian abbey of Bonnefont.7 Villagers, peasants, small shopkeepers and even priests themselves removed the most remarkable pieces from unsupervised sites. Once taken out of their architectural context, the sculptures were stripped of their symbolic meaning, reduced to becoming objects of decoration for gardens, doorways and fountains and scattered fragments of local history. With each passing generation, the provenance and history of these carved stones gradually disappeared from collective memory. Without any historic value, the stones were of little interest to those who owned them, leaving the field wide open for collectors and art enthusiasts to easily acquire them.

However, faced with such negligence, a heritage conscience emerged. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, through publications and excursions of the academic societies, such as the Société Archéologique du Midi de la France (1831) or the Société Académique des Hautes-Pyrénées (1853), local scholars and artists began to express a concern for the state of cloisters. The success of Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France by Baron Taylor and Charles Nodier contributed to arouse historical interest in this “province antiquaire”.8 A taste for ruins grew out of these initiatives.

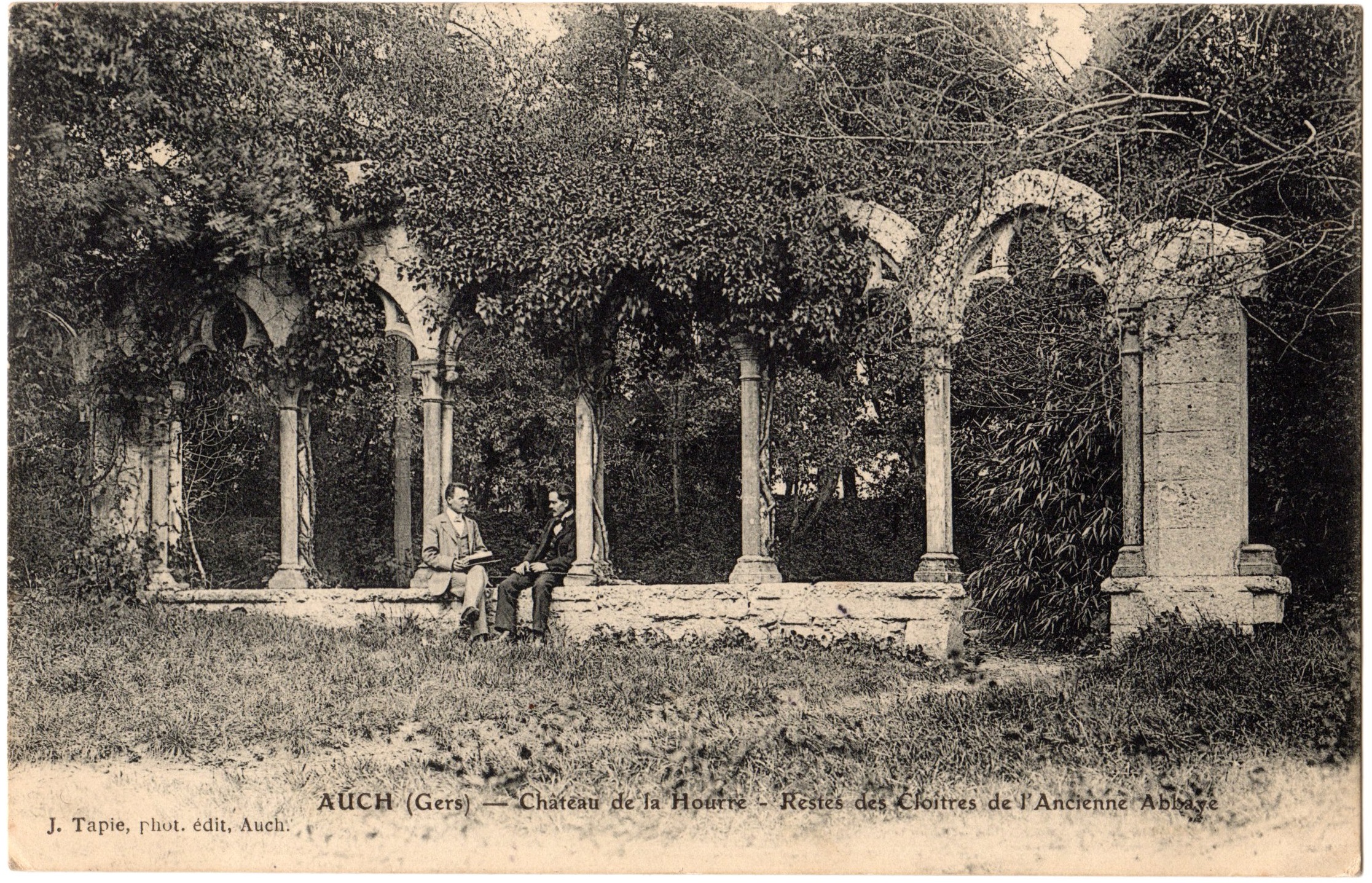

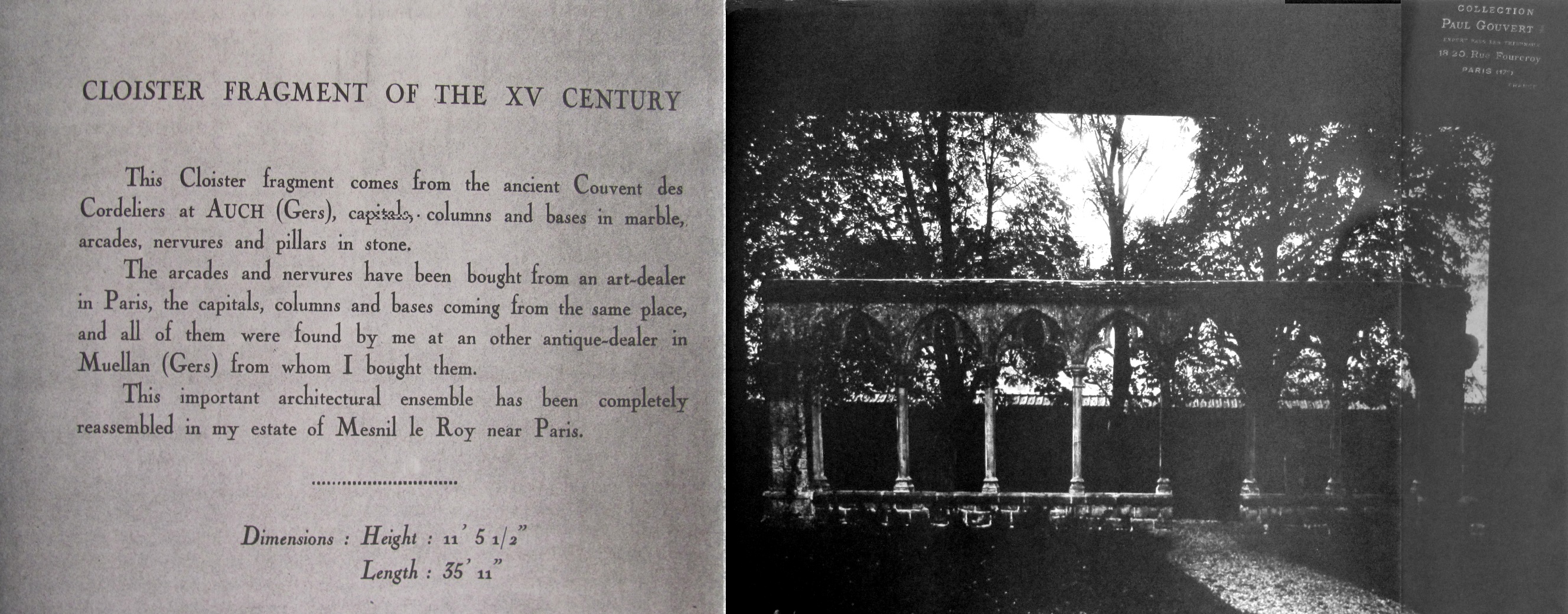

Early on, public figures and descendants of aristocratic families became partial to this type of monumental art and acquired large collections of carved stones that they reunited or included in neo-gothic projects throughout the South-west and other areas of France. In this spirit, Marshal Boniface de Castellane, founder and president of the above-mentioned S.A.M.F, constructed a troubadour-style music pavilion in 1807 which opened through an arcade of gothic columns with capitals from cloisters in Toulouse.9 In Auch (Gers), the David family reassembled the galleries of the city’s Cordeliers cloister in the Hourre park (fig. 5). In 1842, in Villemartin (Aude), Alexandre Guiraud rebuilt the arcades of the cloister of the Carmelites of Perpignan at his property. Likewise, in the Yvelines, a large part of the Saint-Génis des-Fontaines cloister was erected in 1925 in the park of the Mesnuls castle.10 Even in the heart of Paris, a Pyrenées cloister purchased by the art dealer Paul Gouvert has been preserved in the hôtel de la Motte-Montgoubert since 1952.

Fig. 5: Cloistral gallery in the park of the castle of "La Hourre", Auch, Gers, France, photograph ca. 1900

From country homes to Parisian town houses, wealthy art lovers took the trend all the way to their holiday residences on the French Riviera. Following the vogue of the “follies” and romantic architectural creations, European aristocrats and international leading business men all rubbed shoulders while trying to outdo each other with sumptuous villas and elaborate gardens. The park of the Ile de France Villa (Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat), mediterranean home of Baroness Charlotte Beatrice Ephrussi de Rothschild, features among the groves and fountains gothic arcades, bas-reliefs, and even pinnacles casually poised on top of small walls or in between flowerbeds (fig.6). These displays recall those of the gardens of the villa Torre Clementina at Roquebrune Cap-Martin, which feature a grand staircase of greenery interspersed with marble columns, pottery, and sculptures.

Fig. 6: Arcades in the park of the Villa "Ile-de-France", Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, PACA, France

Academic societies and scholars played a central role in raising awareness about these historical vestiges through their publications. Despite their good intentions, the same publications also encouraged a further dispersion of local architectural heritage. As they brought the existence of certain objects or monuments to the attention of art dealers and collectors, they spurred a rush to acquire, dismantle and sell them. It is both surprising and paradoxical that a figure such as respected lawyer Xavier de Cardaillac, descendant of a grand family and active scholar in the academic society of the Hautes-Pyrénées, would sell part of his collection of capitals and bases from Larreule and the wider region11 to the American sculptor George G. Barnard, whom he greatly admired.12 Fernand Pifteau, a member of the Society of Jeux Floraux (Toulouse), a self-taught and passionate bibliophile,13 also was discreetly active as an antiquarian. His dealings are documented by a rather interesting correspondence with George G. Barnard.14 Pifteau sought new prospects outside of war-torn Europe and saw the sculptor as an opening to the American market.

“I often have very beautiful stone columns, porticos, windows, capitals etc. because I specialised in Romanesque and Gothic sculpture quite some time ago – thus I can offer you great pieces – but since my Parisian clients were always quick to buy I hadn’t, until now, worried about finding new markets.[…] Send me word if you are interested and I will do my best to satisfy your requests.”15

Who were these Parisian customers that he referred to? The Pifteau archival material sheds some light on the matter. A letter dated 4 April 1927 from Louis Cornillon, an art dealer in Paris, requests the precise provenance of a door sold to him by Pifteau many years before.16 The door was then remounted by Cornillon on the façade of the music room of Georges and Florence Blumenthal’s Parisian residence.17

Just like his other colleagues in Paris, Cornillon was in direct contact with wealthy clients and museums, often abroad. Jacques Seligmann, George-Joseph Demotte, and Joseph Brummer, all transnational art dealers, opened satellites of their galleries in New York in order to facilitate deals and display their most beautiful pieces. They also published comprehensive annotated catalogues translated into English, as Paul Gouvert’s example entitled “The venerable old stones of France” (fig.7). Nonetheless, they rarely sourced their pieces directly from individuals or from the original sites. They relied on a network of middlemen and amateur antique dealers commissioned to repair, negotiate and acquire the pieces, as Paul Gouvert recalled it:

“In 1952, the countess of M.M. ordered a corner cloister, measuring ten by ten meters for the corner of her house, located in an old building on l’Ile de la Cité. I procured elements of 14th and 15th century carved marble stones originating from cloisters in the Haute Pyrenees through antique dealers in Toulouse, Tarbes, Saint-Gaudens, Pau, and Mirande. I already had in my possession a few bases and cylindrical columns. [...] Then I found arcatures in old stones. I managed to ensure that all elements were of the same ivory colour.”18

Despite competition between them, some of these dealers joined forces to process certain sales together, in order to share the necessary management costs, logistical efforts and complexities of display for certain monuments. Notably, important Paris dealers were often united by strong family ties: the preeminent Parisian art dealer before 1914, Raoul Heibronner19 had a daughter Irène who married the merchant Maurice Stora; the latter’s sister Semha later married the wealthy Belgian-born dealer Georges-Joseph Demotte.

The art dealers had to work fast to satisfy the orders of a very demanding clientele, who sometimes placed substantial catalogue orders for doors, windows, mantelpieces, ceilings and cloister galleries. The flipside of this buying frenzy was an industry of copies.From the 1920s onwards, Louis Cornillon, Georges-Joseph Demotte and Jean Vigouroux were accused of trafficking forgeries. Either deliberately or, more often than not through ignorance, many art dealers improperly attributed false origins to individual fragments and entire reconstructed pieces, and then offered to sell them to a clientele concerned with authenticity.20 Such was the case for the so-called cloisters of “Bonnefont,” “Montréjeau,” and “Samaron”. However, although the rumours of forgeries were sometimes true, as Paul Gouvert admitted during an interview, “personally the problems with authenticity never caused him any issues.”21

Fig. 7: extract of the Paul Gouvert's catalogue, entitled "La Vieille et Vénérable Pierre de France", circa 1930

The government could no longer ignore the calls of scholars and leading figures in academic societies to become involved. Victor Hugo’s pamphlet of 1825 and his scathing article of 1832 titled “Fight the demolishers,” brought the state’s inaction to the attention of the public. In 1830, the role of Inspector General of Historic Monuments was created and a law of 1887 strengthened the means for protecting France’s architectural heritage. However, it was only through the introduction of the law of 31 December 1913, with its more effective arsenal of legal provisions, that progress was ensured. Nonetheless, the lack of actual funding given to the Historic Monuments Commission, the centralised management of cases and the late decrees of implementation (1924) left the majority of architectural heritage and lapidary largely unprotected.

Furthermore, too many monuments had already been dismantled or disappeared. Carved stones were scattered in private hands, and these objects were not protected by the law of 1913, which was restricted to classified monuments. The most effective initiatives, although few in number, were led by the activists of academic societies and organised citizens who sought to save structures in extremis due to imminent danger, like the cloister of the abbey at Flaran or the “Vache d’Alan,” the decorated doorway of the sumptuous residence of the Bishops of Comminges.

The market was growing so fast that it sparked suspicions from academic societies and scholars and later aroused the interest of the authorities, who investigated the outflow to the United States. It was the Duke of Trévise who took on the role of defender of vulnerable architectural heritage. He accused the “interior design” dealers of outright pillage. Finding himself at the heart of the virulent press campaign, Louis Cornillon fought back against Fernand Pifteau and the accusations of forgeries:

“In the long and spiteful article of Mr Mortier, Duke of Trévise, I was not spared. This antique ‘interior designer’ is meant to be me. But let him yell and carry on, I know that I am not a ‘pillaging’ entrepreneur and, to the contrary, I have saved pieces of heritage, which, without me, would have been left to certain destruction. I have just rebuilt at Chalons-sur-Saône a tower from the 15th century which the city council had sold for merely 400 frs a few years ago! The tower was found in the Heilbronner storerooms and to save it I organised its acquisition at the moment of sale to an American friend of France, Mr. F. J. Gould, who donated it back to the city of Chalon, covering all reconstruction costs. Those are the actions of the Duke of Trévise’s so-called gang of ‘forgers’.”22

To summarise, an interest in old stones and the desire by some collectors to include them in landscaped gardens and parks or to reassemble them in galleries fostered a nostalgia for the ruins of destroyed monasteries. Beginning in the twentieth century, American collectors adopted the old world’s fashion and trends, competing with their European contemporaries and advised by their art dealer agents, driven by the busy and dynamic Paris art market.

In the nineteenth century, few Americans were interested in medieval art. In fact, in America, a society marked by its Protestant past, the Middle Ages were considered a “Dark Age”.23 However literature and architecture progressively contributed to a change in mentality. The taste for medieval art was brought into a new intellectual mainstream. The trend for Romantic European literature as well as “Gothic Revival” architecture, popular in the 1840’s mainly due to John Ruskin’s theories and the influence of architects such as Augustus Pugin, brought the history and art of the Middle Ages to America’s attention. Reinvented and idealised by its new admirers, the culture of the Middle Ages became “secularised”, detached from its religious and catholic background.24 Artworks and architectural fragments, acquired through art dealers, became objects of the collecting ambition of their prestigious owners.

Amongst these collectors, Alva and William K. Vanderbilt were the first to acquire in 1889 a collection of significant artworks and pieces from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance for their new home, Marble House, in Newport (R.I.), through the Paris art dealer Emile Gavet.25 Not only did the American couple amass a collection rarely seen in the United States at that time, more importantly they imported Gavet’s layout for the collection including his original taste in interior design.26 Alva Vanderbilt and her husband thus became veritable promoters of “Gothic Rooms” in the United States. Moreover, for Alva Vanderbilt, these prestigious acquisitions would become a political and social tool. The “Gothic Room” was the venue for important Vanderbilt events, such as the engagement of her daughter Consuelo with Charles Spencer Churchill, Duke of Marlborough. The collection and its surroundings were the perfect setting to foster links between the new and old worlds, between American fortunes and important families of the European aristocracy. Their international reputation as collectors and philanthropists greatly helped elevate the family’s standing to society’s highest echelons.27

The collection of Alva Vanderbilt’s contemporary Isabella Stewart Gardner added a new dimension to the scene. Isabella Gardner was self-taught and meticulously collected piece by piece.28 She took regular trips to Europe, followed up on all stages of her collection and building project and personally supervised the construction of the Venetian-inspired building that would house the installation of her collection.29 Her collection represented first and foremost her personal vision. The inscription on the front of her museum sheds light on her motivations: “It is my pleasure” a romantic phrase reminiscent of “my sole desire,” seen on the sixth tapestry of “the Lady and the Unicorn” (fig.8).

Contrary to Alva Vanderbilt’s Gothic Room and the Revival villas, Isabella Stewart Gardner was the first to include original architectural elements and entire monuments in her collection, as seen in the cloister bordering the main courtyard of her mansion. She was also keen to protect her collection and projects from the “Elginist” practices of untrustworthy dealers and collectors. In 1904, the journalist and Boston town-planner, Sylvester Baxter wrote:

“Particular stress should be laid upon the circumstance that the materials wrought into this building have in no instance been obtained from any structure that was demolished or dismantled for the purpose or that to this end was deprived of any feature. The spirit in which Fenway court was conceived and carried out was one of two great reverence for monuments of the past to countenance in any degree their destruction or their spoliation for its own purposes. Every piece of ancient stone that has entered into these walls either came from buildings that already had been demolished or condemned to demolition or was a feature removed for the sake of a restoration duly determined upon.”30

Gardner’s collection pre-empted by over a decade the pioneering collection of French architecture: The Cloisters of George Grey Barnard.31

George Grey Barnard differs greatly from the many portraits attributed to him. The son of a preacher, he did not come from a fortunate and wealthy background like the collectors who either inherited vast fortunes or created them as industry moguls. He was a multi-faceted character. At once a sculptor, art lover, and art dealer32 he merely imitated the sometimes-antiquated ways of collectors and art dealers whom he rubbed shoulders with during his regular trips to France. The showcase for his collection, The Cloisters in New York, became a model for a whole generation of collectors, and was emulated as far as the American West coast and beyond.

In 1902, George Grey Barnard won the prestigious competition to become the sculptor of sculptural elements incorporated in the new façade of the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg. After finishing the sketches and models for this work, he moved with his family to France, where he wanted to carry out his ambitious project. This was a turning point in his career as an artist and more importantly, for his future career as a collector/antique dealer.

Fig. 8: Inscription on the front of the Isabella Stewart Gardner museum, Boston, Massachussetts, United States

However, the sculptor and his family quickly fell into financial difficulties and were forced to seek new sources of revenue. During his first stay in France as a poor young artist, Barnard had the chance to resell a few antique pieces. Similar to Louis Cornillon and Georges-Joseph Demotte’s practices, he procured his sculptures and fragments of medieval carved stones from individuals and, more often, from local antique shops. Thus, he succeeded in making a substantial profit through the Parisian art dealers.33 He subsequently asserted that selling his found treasures was “a thousand times easier than [selling] his own artworks (…)” and admitted making “marvels”.34 Born out of necessity, his new-found role of “antique dealer” would become his principal job for one whole year.

However, a shift was already underway. No longer would he sell his pieces to an exclusively French antique dealing clientele, he would broaden his reach to include American collectors and museums. G.G. Barnard travelled around the French countryside, regions rich in medieval ruins. He spent a few weeks “hunting”35 in Bourgogne, in the Vosges and in the Southwest (Languedoc et Pyrenees) and acquired large sections of three cloisters: Saint-Michel de Cuxa, Saint-Guilhem and “Trie.” As his wife explained: “George is again in the Pyrenees trying to complete a cloister which he and I have purchased as an investment”.36

As soon as he bought them, he immediately began the search for a buyer, ideally a wealthy American like Andrew Carnegie or Isabella Stewart Gardner, or an American museum like the Art Institute of Chicago. It should be noted that prices varied with buyers. For example the cloister of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa which was sold in one lot including a monumental door, was estimated at US$100,000 for “Carnegie or a rich man” but would be subsequently reduced to $50,000 if a museum were interested. The same practice was adopted for the “Trie-Larreule” collection. G.G. Barnard offered just fourteen “Larreule” capitals to Mrs Gardner for the price of US$25,000 but envisaged offering the entire “Trie-Larreule” collection to a museum for the same price.37 Sales to museums or famous collectors might also contribute to raise his prestige and improve his position in the market.

Indeed, until 1913, he contacted numerous potential buyers and museums, but none were willing to invest large sums in imposing monumental ensembles that still carried little recognition in the art market. Moreover, Barnard was a rising figure in the American art scene at that time, but he was not yet accepted as one of American or European social elite or as a well-known art dealer. In addition, the architectural pieces he was trying to sell imposed a similar challenge. They were not artworks from known artists or workshops, but for the most part, anonymous. Moreover, Barnard had neither a gallery nor a catalogue raisonné. His descriptive letters addressed to potential buyers were not a sufficient draw for them to truly appreciate the opportunity at hand. Only Stephen Carlton Clark, son of G.G. Barnard’s mentor Alfred C. Clark, bought a collection of columns originating from the cloisters of Trie and Larreule for the patio of his Manhattan residence. Having known the Clark family for over thirty years, G.G. Barnard was trusted by the young Clark. Due to their personal relationship the sale of the columns was swiftly finalised.

It soon became clear to G. G. Barnard – more of a dealer than a collector after all – that he needed to have his own gallery to showcase his entire collection. The Cloisters, born from a business strategy, was built in 1914 on his property on Fort Washington Avenue (Washington Heights).38 It was a revelation for the world of collectors and museums across the Atlantic. The press, artists, art historians such as Arthur Kingsley Porter and museum curators gave raving reviews of the works of art and their installation.

Inspired by his visit to The Cloisters, Frederic A. Whiting, director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, designed the rooms of his museum in a similar layout.39

“My first instinct on returning to my office is to write you at once expressing my appreciation of the splendid thing you are doing in your Gothic museum and of the wonderful opportunity it is going to give to all art lovers to see these beautiful architectural pieces under such ideal conditions[...]We are planning in our own building a garden court which we hope eventually to make a beautiful repository for Gothic and Renaissance architectural fragments [...] After seeing the large amount of material that you have gathered, it occurred to me that you might have some capitals, figures or other carvings which you could spare”.40

Within just a few months, his collection which had garnered next to no interest or attention from private collectors or museums, suddenly gave a statute of expert to Barnard and attained a high reputation.41

The Detroit museum, which in 1923 added the chapel of Château Herbéviller (Lorraine),42 and Cleveland museum were the first to recognise The Cloisters as a a model to be emulated. Following their lead, the museum of Philadelphia acquired G.G. Barnard’s second collection. A few years later, “composed cloisters” were constructed at the Museum of Toledo43 and in 1933 the Dayton Art Institute adorned its gallery in the same fashion.44 In 1948 a set of French cloisters was installed as a “period room” at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas.45

Even the world of art dealers expressed admiration for the collection.46 In a letter he sent to his friend George Grey Barnard, the Parisian antique dealer Edouard Larcade admitted to having been inspired by The Cloisters in New York:47

“I haven’t been to New York in two years because I’m like you, I am so in love with the Gothic period that I bought an old abbey in Nice which I completely restored and added Pyrenees cloisters to..[…]They are composed of a sublimely coloured white marble Greco-roman cloister and an exterior cloister from the 12th century also in marble, a very beautiful thing.”48

In April 1923 in Nice, Larcade acquired Count Appraxine’s property baptised “the Abbey of Roseland.” Following in the footsteps of his predecessor, he immediately undertook a series of transformations that included not only the gardens but also various buildings. He created a complex of features: a chapel, a “fake” cemetery, and cloisters made up of “antiques” and medieval sculptures (fig.9).49 Open on three sides, the cloisters are comprised of two series of columns and capitals, belonging to different periods and structures. The first line of twenty-six columns would come from the Daurade monastery in Toulouse; the exterior arcade features elements attributed to the cloister of Bonnefont-en-Comminges.50

Fig. 9: Cloister in the "Abbaye de Roseland", Nice, France

In fact, these cloisters lost their role as a testimony of the past and became fantastic recreations, products of their owners’ imagination, sometimes travelling to far-flung destinations. The above-mentioned Roseland abbey in Nice inspired George Huntington Hartford, heir to the A&P Tea Company to erect an ensemble of a cloister with a double gallery in Paradise Island, Bahamas in 1962 (fig.2), supposedly originating from the Augustinian monastery of Montréjeau.

George Grey Barnard exported his museum concept from France and first implanted it on the East Coast of the United States in 1914. The museum was then emulated in the Midwest in the early 1920s and continued its spread towards the west. It was not a museum director but one of the most important collectors of the time, William R. Hearst, who developed the next great medieval museum project, a veritable counterpart on the West Coast, to the “Cloisters of Mr Rockefeller.”51 However, his museum integrating medieval architecture never got past the drawing board stage and remained in the imagination of William R. Hearst.

Alas, most of the William R. Hearst’s collections were sold from 1937 and numerous sets of columns and architectural pieces were scattered throughout the country, for example the “Samaron” cloister which perfectly illustrates the destructive frenzy over monuments that existed in the United States at that time. This cloister is actually a collection of columns, bases and capitals assembled by the dealer Georges-Joseph Demotte in the1920s and acquired by William R. Hearst in 1923. This disparate collection had two potential destinations: the millionaire’s own villas or, more probably, the collections for the ambitious medieval art museum that he planned to build in San Francisco. Due to the financial crash of 1929, his ambitious project and the cloister of “Samaron” remained in storage in the Bronx until the 1940s. In 1944 the dealer Joseph Brummer acquired several columns;52 others were taken into private collections, such as that of ambassador George C. McGhee in his Virginia residence and that of Richard A. Rainsford in Connecticut. The later collection was resold and partially remounted in the museum of Bob Jones University at Greenville. In 1954 a large group of columns was given by the Hearst foundation to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Unable to rebuild them in the galleries of The Cloisters museum, they were sold at auction to a private collector in California in 2008.

The “love affair” with cloisters in the United States is somewhat faded today. Nevertheless, its history allows us to trace opportunism by art dealers, the intellectual curiosity of a collector like Isabella Stewart Gardner, the sheer ambition of George Grey Barnard, and even museum acquisitions born of necessity, or a need for a challenge as in William R. Hearst’s project. Collecting and erecting cloisters in America in the early twentieth century reflected a renewed and reinterpreted taste for what the French refer to as “Haute Epoque” art and more particularly, for the monumental aspect of the art of the Middle Ages. Moreover, to understand these translocated monuments is also to question the elaboration of the re-assemblies: their forms, their models, their evolutions; it is also to refine our knowledge of the origins of these fragments by tracing the history of attributions, by investigating successive acquisitions, by trying to distinguish the original pieces from the modern ones. Once the field of investigation has been refined, it is to renew the hypotheses of attribution by comparative analyses with sculptures that have remained in France, in situ, stored or conserved in museal institutions or private hands; it is finally hoped to reintegrate these fragments into an enriched artistic and architectural corpus.

Responding to these different issues is therefore a challenge in multi-disciplinary research relative to archaeology, contemporary history or sociology, because this medieval French heritage is as much witness of the Middle Ages as monuments of the twentieth century.

Céline Brugeat completed her PhD at the university of Toulouse in 2016 with a thesis on American collections of Gothic cloisters.

1 Sebastien Marty, Le Cloître de Goering est revenu, in La Dépêche, 09/25 (2003); author’s translation.

2 Title of a catalogue of the art dealer Paul Gouvert, published around 1930.

3 Richard W. Emery, The Friars in medieval France (London and New York), 1962.

4 Archives of Larreule, Registre des délibérations, 1851-1879, August 13th 1854.

5 Archives départementales des Hautes-Pyrénées , Francez 16 J. Abbé BRUNET, Larreule. Esquisse historique (n°34).

6 The Cloisters archives, The George Grey Barnard papers, box I, folder 4. Louis Cartérot’s letter, 22 October 1908.

7 Edmond Duméril, Pierre Lespinasse, Une abbaye cistercienne du Comminges, Bonnefont. Etude archéologique des restes 1926, 7-8. See also Dom. Saint-Laurent, Saint-Martyri, ou St Martory, la vie, ses reliques, son culte, son église (Toulouse, Imprimerie St Cyprien), 51 .

8 Odile Parsis-Barubé, La province antiquaire. L’invention de l’histoire locale en France (1800-1870), (Paris: CTHS, 2011).

9 Louis Peyrusse, Le style troubadour à Toulouse, in Monuments historiques, July-August (1981), 46-49.

10 Géraldine Mallet, Les cloîtres démontés de Perpignan et du Roussillon (XII-XIVe siècle), (Perpignan: Édition des Archives communales, 2000).

11 Archives of the Metropolitant Museum, of Art (AMMA), Department of Medieval Art (DMA), objects files, Folder Trie, correspondence between Xavier de Cardaillac and George Grey Barnard, letters dated 1906/1907.

12 AMMA, DMA, objects files, folder Trie, Xavier de Cardaillac’s letter, 5 February 1907.

13 Toulouse à l’époque romantique, (Toulouse) 1994, 9.

14 Archives of American Art (AAA), Georges Grey Barnard papers, serie 2, box 1, folder 11.Correspondence, 1914-1916, F. Pifteau’s letters, 21 January 1916.

15 Archives of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (APMA), George Grey Barnard papers, Serie I, box 8.folder 8. Misc. business correspondencere: transactions. Date: 1908-1938. F. Pifteau letters, 2 February 1914.

16 Bibliothèque universitaire de l’Arsenal (Toulouse), Archives of Fernand Pifteau, RespPfEst 11-12-1, Louis Cornillon’s letters, 4 April 1927.

17 The Cloisters (acc. num. MMA 35.35.14).

18 Paul Guth, Les souvenirs d’un marchand de sculptures, in Revue Connaissance des Arts. 12/15 (1953) 41-45.

19 From 1887, Raoul Heilbronner (ca 1849-ca 1941) was major figure on the Paris art market on the eve of the First World War. His gallery at 3 rue du Vieux-Colombier exhibited on three floors an impressive collection of medieval and Renaissance works of art. German-born, Heilbronner was forced into exile and his properties were sequestered by French government in 1914 and sold in the 1920’s.

20 Jacques, Lapart A propos des sculptures revenues d’Allemagne à Berdoues (Gers) en 2003: quel rôle l’antiquaire parisien Paul Gouvert a-t-il joué dans leur périple? in Bulletin de la Société Archéologique du Gers , (2010/2), 290-301.

21 Paul Guth, op.cit. 43

22 See footnote 17.

23 Ray Allen Billington, The protestant crusade 1800-1860, A study of the origins of American Nativism (New York: Quadrangles paperbacks, 1964), 514.

24 Virginia Brilliant, Introduction: Gothic in America, in Journal of the History of Collections, 27-3 (2015) 291-295.

25 Aurélie Letellier, Medieval and Renaissance in nineteenth century Paris, in Journal of the History of Collections, 27-3 (2015) 297-307.

26 Paul F. Miller, “Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, arbiter elegantiarum and her gothic salon at Newport, Rhode Island”, in: Journal of the History of Collecting, 27-3 (2015) 347-362.

27 Charles J .Burns, ‘From Medici to Bourbon : The Formulation of Taste and Evolution of a Vanderbilt Style’ (London: University of London, MA Thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, 2007), 19.

28 Cornelius Clarkson,Walter Cahn, Rollin van N. Hadley, Sculpture in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Boston: The Trustees, 1977).

29 Robert Colby, Palaces Eternal and Serene : The Vision of Altamura and Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Fenway Court, in Bernard Berenson : formation and heritage, (Florence: Villa I Tatti, The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, 2014).

30 Sylvester Baxter, An American Palace of Art, The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in the Fenway Court, Boston, in The Century Magazine, 1904/01, 362-382. Baxter payed a great attention to the preservation of heritage, he was, notably, the first secretary of the Massachusetts Metropolitan Park Commission at Boston.

31 Shirin Fozi, American Medieval. Authenticity and the influence of Architecture, in Journal of the History of Collecting, 27-3 (2015), 469-480.

32 Elizabeth B. Smith, “George Grey Barnard: Artist/ collector/ Dealer/ Curator”, in Medieval art in America: patterns of collecting, 1800 – 1940 (University Park: PA State U. Palmer Mus. A., 1996), 133-142.

33 Harold Dickson, The Origin of the Cloisters, in Art Quarterly 28, (1965), 253-271, 256.

34 Idem.

35 Dickson, 257.

36 Idem.

37 J.L. Schrader, George Grey Barnard: The Cloisters and The Abbaye, in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 37-1 (Summer 1979) 2-52.

39 Holger A. Klein. Building Cleveland’s Medieval Future : the origins and history of the Cleveland Museum’s medieval collection, in To Inspire and Instruct: A History of Medieval Art in Midwestern Museums, ed. by Christina Nielsen (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars publishing, 2008), 54-69.

40 Archives of the Cleveland Museum of Art (ACMA); Records of the Director’s office (RCO). Frederic A. Whiting, box 25, folder 242, Frederic A. Whiting’ s letter, 9 November 1914.

41 ACMA, RCO, Frederic A. Whiting, box 26, folder 243.

42 Acc. num. DIA, n° 23.147, Peter Barnet, “The Greatest epoch”: Medieval art in Detroit from Valentiner to “Big idea”, in Christina Nielsen, ed., To inspire and instruct: a history of medieval art in Midwestern museums (Newcastle : Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008), 54-69.

43 Roger Mandle, The Cloister, in Museum News: The Toledo Museum of Art, 21-3, (1979), 56-69.

44 Mary B. Shepard, It’s chaste beauty: cloistered spaces in Midwestern art Museum, in Christina Nielsen, ed. To inspire and instruct, 92-93.

45 Dorothy Gillerman, ed., Gothic sculpture in America, Vol. 2 : The Museums of the Midwest, Publications of the International Center of Medieval Art, 4. (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 212.

46 Calvin Tomkins, The Cloisters...The Cloisters...The Cloisters..., in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 28-7, (1970), 312.

47 APMA, George G. Barnard papers, box 27. folder 19.

48 AAA., George G. Barnard papers, Correspondence 1924, fol. 17-1924.

49 Jean Marx, In Situ n°2, un dossier de protection monument historique : la demeure dite «abbaye de Roseland», (DRAC Paca: MCC, 2002).

50 Jacqueline Caille, Quitterie Cazes, Sainte-Marie la Daurade à Toulouse: du sanctuaire paléochrétien au grand prieuré clunisien médiéval, (Paris: CTHS, 2007).

51 William A. Swanberg, Citizen Hearst (New York: Charles Scribner Sons, 1961), 268.

52 The elements were dispersed in several sales in 1949. See Céline Brugeat, Saramon ou Samaron (sic), appellation d’origine antiquaire: légende d’un cloître disparu, in Actes de la journée des archéologues gersois (Gimont), forthcoming.