ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Barbara Pezzini

In this article I propose some general observations and guidelines to explore afresh the nexus between the art market and artistic production. To do so, I investigate these issues within the historical frame of nineteenth century Britain, a time when contemporary national painting enjoyed great success: it commanded high figures, critical acclaim and collectors’ attention. In such a buoyant commercial setting, artists assumed multiple, often co-existing, strategies for the marketing of their oeuvre. Insightful scholarly investigations have been so far dedicated to artists as savvy professionals, for whom the relationship with the trade was principally experienced as a business connection. There were, however, alternative models of interaction, such as the close rapport that developed between the landscape painter John Linnell and the art dealer William Agnew. Linnell’s relationship with Agnew is identified here as a key element of Linnell’s success. Linnell and Agnew not only devised marketing tactics together, but also discussed Linnell’s artistic direction. This article, then, presents a case study of commercial and artistic cohesion, albeit not without its own tensions, where the dealer supported, intellectually and practically, the artist’s creative output. Ultimately, this article aims to demonstrate the many connections between the aesthetic and the commercial within the art trade, defined here as the “art” and the “market” elements of the art market.

This article is based on a historical case study: the reconstruction of the relationship between John Linnell – an artist defined in his 1882 obituary as “the most powerful of landscape painters since Turner died” – and William Agnew, one of the most prominent art dealers in nineteenth century Britain.1 The recollection of their personal and professional association through letters and financial records, however, is the springboard towards a wider research contribution. It allows to consider afresh artist/dealer relations and to propose some methodological observations on the nexus between artistic production and the art market, observations that may have the potential to translate from nineteenth-century Britain to other contexts.2

The relationship between dealers and artists in the nineteenth century has been previously described as fraught with conflicts and tensions.3 For instance, in 1893, the writer and critic George Augustus Moore, who trained as a painter in Paris during the 1870s, penned a caricature description of its dynamics.4 Moore took the side of the artist, and denounced the typical London dealer as a patronising bully: a histrionic, unlikable character who preaches, communicates through “sneers and sarcasm” and is obsessed with prices and with pleasing the popular taste. The artist, conversely, is depicted as the dealer’s victim: a mild creature, “timid” and “struggling”, who perseveres in his unpopular efforts in the name of art:

“[T]he artist is visited by a showily dressed man, who comes into the studio whistling, his hat on the back of his head. This is the West-End dealer: he throws himself into an arm-chair, and if there is nothing on the easels that appeals to the uneducated eye, the dealer lectures the artist on his folly in not considering the exigencies of public taste. On public taste-that is to say, on the uneducated eye-the dealer is a very fine authority. His father was a dealer before him, and the son was brought up on prices, he lisped in prices, and was taught to reverence prices. He cannot see the pictures for prices, and he lies back, looking round distractedly, not listening to the timid, struggling artist who is foolishly venturing an explanation. Perhaps the public might come to his style of painting if he were to persevere. The dealer stares at the ceiling, and his lips recall his last evening at the music-hall. If the public don’t like it-why, they don’t like it, and the sooner the artist comes round the better. That is what he has to say on the subject, and, if sneers and sarcasm succeed in bringing the artist round to popular painting, the dealer buys; and when he begins to feel sure that the uneducated eye really hungers for the new man, he speaks about getting up a boom in the newspapers.5

Moore’s description of a disinterested artist, a typology that already complies with the Modernist narrative of art as a hallowed object distant from any commercial consideration, has been challenged again and again in the current literature.6 For instance, Grischka Petri demonstrated how James McNeill Whistler attempted to manipulate increases in prices of his works, and recently Julie Codell explored how Victorian artists were open towards their economic and social success, and how they utilised their networks to gain financial stability and social recognition.7 The other side of this relationship, the role played by the Victorian art dealer, has not yet been the subject of closer scrutiny.

The study of art dealers in general, however, is flourishing.8 Commercial galleries have been increasingly interpreted, in the words of Pamela Fletcher, as representing “a transformative way of viewing art”, and Fletcher and others have emphasised the hybrid cultural quality of the dealer, a figure in-between the shopkeeper and patron.9 The co-existent cultural and commercial values of art dealers were also discussed by Raymonde Moulin who defines dealers as having “ambiguous motives” in her study of the French art market.10 In some cases, Moulin writes, dealers are “like patrons of the arts, except that the disinterest of the patron is in contradiction with the logic of the dealer’s profession.”11 This article draws on these reflections of the complex nature of dealer/artist relations, and aims to continue the investigation of the cultural role of dealers by adding fresh archival evidence through the case study of William Agnew and John Linnell. Without wanting to reverse Moore’s narrative entirely, and present “timid”, “struggling” dealers fighting in the name of artistic integrity vis-à-vis aggressive artists marching towards commercial recognition, this case will expose the limitations and inaccuracy, of Moore’s uncompromising, clear-cut narrative, by showing how the encounter between the ideal and commercial coexisted in the words and actions of both artists and dealers.

In Marketing Modernism, a study of (mostly French) structures of the art market, Robert Jensen identified two kinds of dealers: the “entrepreneurial” dealers, who had an openly commercial attitude, and the “ideological” dealers, who concealed their commercial tactics under the rhetoric of ideal disinterestedness and professed to act for art’s sake rather than for financial profit.12 The ideological model has been principally identified in modernist art dealers, such as Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and Léonce Rosenberg .13 In this article I build upon Jensen’s distinction, locating it in Victorian Britain.

I argue, however, that the entrepreneurial and ideological categories are not to be seen as a clear-cut dichotomy, but that the entrepreneurial (i.e. the “market” element of art dealing) and the ideological (i.e. the “art” element), represent different strategies and positions that can be displayed simultaneously, and adopted by dealers and artists alike. This synthetic stance is principally indebted to two intellectual strands. Firstly, the sociological theorisations of Pierre Bourdieu, who has identified commercial and cultural motivations as intrinsic to the field of cultural production and its operators.14 Secondly, the more recent work by economics sociologists Viviana Zelizer and Olav Velthuis, who have demonstrated the coexistence of cultural and commercial components in the art world, including the art trade.15

The connection of art dealer William Agnew and artist John Linnell, then, offers an opportunity to explore this profound interdependence of culture and commerce, by presenting a case in which the ideological and entrepreneurial positions coexist simultaneously in the artist and the dealer. The art dealer Agnew showed many entrepreneurial traits: he was openly commercial and displayed a great pride in the business aspects of his profession.16 In parallel to this, however, he claimed, like Jensen’s ideological dealer, to advocate a particular type of art for its qualities, and to support art for art’s sake. Similarly, Linnell wrote in an ideological manner about art, as well as being entrepreneurial and promoting his business interests fiercely.

Linnell and Agnew operated in a booming art market. After the recovery from the 1836-1842 depression, London had established itself as the centre of international art commerce, as well as the premier national market for contemporary art. 17 According to data gathered by Thomas Bayer and John Page, the auction market for contemporary art was one and a half times the size of the old masters market during the 1850s, but by the 1870s it had grown to surpass it by two and a half times.18 Bayer and Page’s statistical data of growth, however, merely confirm a well-known situation, noted at the time and also investigated in twentieth-century scholarship. Notably, historian of taste and market analyst Gerard Reitlinger in 1961 coined the definition of mid-nineteenth century Britain as “the golden age of the living painter”, a term that was later also adopted by Bayer and Page.19 Reitlinger pointed out that even the rebellious Pre-Raphaelite painters, whose Brotherhood was founded in 1848, did not have the market of rejected outcasts: they were paid well, attracted many customers, and art speculators were quick to invest in their work.20

In the mid-nineteenth century bullish market, artists assumed multiple strategies for the successful marketing of their oeuvre. From travelling exhibitions of single sensational works, as in the case of William Holman Hunt and Rosa Bonheur, to the presentation of their lifestyle as a commercial operation, as in the cases of James McNeill Whistler and Frederick Leighton, much work has been so far dedicated to British-based artists as savvy businessmen in an urban public setting, where the relationship with the trade was indicative, at the same time, of conflict and collaboration, but was principally experienced as a business connection. 21 Yet there were also other ways for artists to market their work successfully in Britain, and some dealers and artists developed relationships that went beyond the commercial deal. This article focuses on one such alternative model, one that finds the dealer and the artist in private, personal contact.

Fig. 1: John Linnell, Self-portrait, oil on canvas, ca. 1860 (London, National Portrait Gallery). Creative Commons Licence.

John Linnell [Fig. 1] , the son of a London woodcarver, frame maker and picture dealer, was immersed in the commercial aspects of art since birth.22 His talent for painting demonstrated early: in 1805, aged thirteen, he entered the Royal Academy School, and he soon exhibited pictures at the Royal Academy and at the British Institution.23 Linnell began as a well-connected practitioner at the centre of the art establishment, but he also presented the characteristics of an outsider. For instance, even though he exhibited at the Royal Academy often and with great success, Linnell was never elected to its official membership, a fact that would cause him much distress. Linnell practiced a militant and Nonconformist form of Christianity that marked him as an outsider. Deeply religious and an attentive reader of the Scripture, he did not believe in the Anglican Church and rejected its religious rites, including at his own wedding, which was celebrated with a secular ceremony in Scotland.24 An essential part of Linnell’s faith was the study of nature: he regarded painting landscapes as a response to the work of God, and his pictures, especially the post-1848 ones, are infused with Christian symbolism. In his “Dialogue upon Art” published in The Bouquet of November 1855, Linnell expressed his belief in the spiritual and moral nature of art, speaking in the voice of the ideological artist (emphasis added):

“The skill of imitation is wasted unless the representation teaches us some moral or spiritual truth. The business of The Art should be I think to create spiritual perceptions and all the powers of imitation, the Skill in Design, in Colouring and Expression – all are to be used to this end. The artist has indeed to deal with the senses but his object should be to reach the heart – the inner man through that medium.”25

Linnell carried his religious and idealist beliefs throughout a long and successful professional life. First active as landscape and genre painter from 1809 to 1821, he then experienced a profitable mid-career as a society portrait painter from 1821 to 1847. Around 1848, when he was fifty-five years old, Linnell used the capital accrued as portrait painter to buy land and property, the now-demolished Redstone House at Redhill in Surrey, South East of England [Fig. 2]. Linnell’s move to the country was not a retirement but marked the beginning of his later career, which lasted until his death in 1882.

Fig. 2: John Linnell, My Garden at Redhill, oil on canvas, 1858 (Wolverhampton Art Gallery). Creative Commons Licence.

In these years Linnell returned exclusively to landscape painting, creating a new, intensely personal formula of wide vistas interspersed with smaller figures of a symbolic quality. Like John Constable, Linnell’s panoramas did not render celebrated landscapes, but the English countryside around him. He painted the hills, valleys and rivers of the neighbouring counties of Surrey, Kent and Sussex under vast skies covered in creamy white clouds, often shown in the fleeting moments of orange sunsets or under the purple-grey light of a full moon [Fig. 3]. Linnell transformed familiar surroundings into depictions of nature that combined epic, romantic and realistic tones with a distinctively individual palette of muted greens, yellows and browns [Fig. 4]. In spite of the technical skills and atmospheric quality of the later works, the current critical assessment of Linnell’s importance centres on his early output, and on his relationships with his fellow artists William Blake and Samuel Palmer, whereas his later work is, at the moment at least, less valued.26

Figure 3 John Linnell, Harvest Moon, Oil on Canvas, 1858 (London, Tate Britain). Creative Commons Licence.

Linnell moved to Redhill with his large family: the Linnells had nine children of which two, James and William, were successful artists themselves. There is evidence that his daughters exhibited works as well, although their output is, as yet, undiscovered. His daughter in law Elizabeth Linnell, was also a talented painter, as visible in the only extant example of her work in a public collection, Mountain Track (Brighton and Hove Museums and Art Galleries). The Linnells were not mere idealists but also very entrepreneurial artists. The family acted as a business, “Linnell and Co.”, in which John was the patriarch and managing director at the same time, and they enjoyed critical recognition, commercial success, and achieved a very comfortable standard of living.

A similar combination of idealism and commercial nous can be found in the art dealers Agnew’s. Founded by Thomas Agnew Senior and Vittore Zanetti in Manchester in 1817, Agnew took over as sole owner when Zanetti retired to Italy in 1835. In 1851, when Thomas Agnew Senior’s sons, William Agnew and Thomas Agnew Junior, joined him in partnership the firm took the name of “Thos. Agnew and Sons”, although it was soon known simply as “Agnew’s”.27 During the 1850s and 1860s Agnew’s was an expanding business, with branches in Exchange Street in Manchester, Dale Street in Liverpool (opened 1858) and Waterloo Place in London (opened 1860).28

Fig. 4: John Linnell, Sunset. Home, the Last Load, oil on canvas, 1853 (London, Tate Britain).

Creative Commons Licence.

There is no doubt that the Agnews were entrepreneurial dealers. In the period 1850-1870 they ran a growing business, which increasingly specialised in paintings, selling modern British pictures exhibited at the Royal Academy and works by “Deceased English Masters” such as J.W.M. Turner, Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough to industrialists, bankers and aristocrats.29 Agnew’s was a financially successful firm, and the family owned substantial capital which allowed them to be generous with artists, as they could afford to carry some losses or hold stock on their books for longer if necessary.30 This long-term policy forged good relationships of repeat custom with artists, which ensured a steady supply of high quality works to the firm. Agnew’s took good care of buyers as well as suppliers. They had a clear pricing structure for buying at auction – 5% when buying on commission and 10% when work was selected from their stock – and their margins on works bought from artists were also applied with consistency. Agnew’s transparent business practices established a relationship of trust with their clients and created a wide, solid base of buyers for their wares.

Fig. 5: Frank Holl, William Agnew, Watercolour, 1883 (London, Private Collection). Creative Commons Licence.

The Agnews were also ideological dealers who promoted contemporary art. They had associated – personally as well as professionally – with a wide range of British and European artists. William Agnew [Fig. 5], who succeeded as head of the firm when his father Thomas Senior retired in 1861, had particularly warm relations with artists. Letters in the National Gallery archive, as well as his correspondence with Frederic Walker and George Frederic Watts, show the profound friendships and rapport that he developed with some of the painters whose works he sold. 31

The Agnew family’s idealist beliefs also translated in their religious affiliations, philanthropic deeds and civic spirit; the Agnews, like the Linnells, were progressive in politics and deeply religious, their practice, like the Linnells’, was nonconformist: they belonged to Swedenborg’s New Church, a Christian denomination that interpreted the Grace of God as the result of good deeds and saw Faith as an active pursuit.32 This practical idealism imbued many of the family’s choices, and elsewhere I have defined the Agnews as civic dealers: art traders with a developed public spirit and strong ethics of good citizenship.33 For instance, Thomas Agnew was one of the founders in 1824 of a Cheap Day School for children in Manchester, on the board of which he served for many years.34 He was also a long-standing Councillor in the Commission for Public Security for Salford, had been elected as the town’s Mayor in 1850, and he served as Executive Committee member of Salford Free Library and Museum from 1838 to 1871.35 Salford Council records confirm that Thomas Agnew participated at council meetings actively and regularly and he contributed much to the running of the town and to the success of the museum, which peaked at over 600,000 visitors per year and held a successful Summer Exhibition modelled on the shows of the Royal Academy.36 William Agnew followed in his father’s footsteps, and he too was a philanthropist of progressive beliefs and a successful politician. A friend and supporter of William Ewart Gladstone, William Agnew would later be elected by a landslide as Member of the Parliament for the Liberal Party in the South Lancashire constituency in April 1880.37

John Linnell sold his paintings and watercolours to Agnew’s from 1853 to 1869. According to Evan Firestone, who first reconstructed John Linnell’s relationship with picture dealers, Linnell operated on strictly business-like terms with the trade, requesting deposits in advance and payment in full on delivery, while insisting on decisions being recorded in writing and signed by both parties.38 Undoubtedly, in his letters to Agnew’s, Linnell demonstrated fully his entrepreneurial spirit. As he wrote to Thomas Agnew about A Forest Road (now Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery) [Fig. 6] in 1853 (emphasis added):

The price of the work is 500 guineas [£٥٢٥]. It is the only picture I have undisposed of, and the same price has been received for similar works. In order to save trouble be advised that an offer of a lesser price will be useless. I expect to be able to improve the picture considerably. [...]39

And then, again, to William in 1859:

I again took up the Forest Road picture and worked upon it whenever I saw that I could improve it until the beginning of this year when I considered it as complete as I could make it, and placed it in my family living room where I had many offers for it at more than my actual price for the size. But as you were the first to come to my terms this picture was sold to you with every possible assurance on my part that no pains have been spared by me to make it the best picture of the class that I can produce. [...]40

Figure 6 John Linnell, A Forest Road, Oil on Canvas, 1853 (Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery).

Creative Commons Licence.

Linnell’s meticulous attention to the administrative aspects of his sales and the firm control he took of his prices have coloured the view of his relationship with dealers as merely entrepreneurial practice. Undoubtedly Linnell and Agnew had an established business relationship: in the period from 1862 to 1868 Agnew’s London Stock Books record that Agnew’s bought 34 works by John Linnell, of which 26 were purchased directly from the artist, accruing a total profit of £1,900.41 William and John had a trusting relationship: they held an open business account and William freely advanced money for works that he commissioned from John. In addition, a fresh reading of the many letters that he and William Agnew exchanged demonstrates that their relationship went well beyond the commercial, they became friends. The two men exchanged visits, food, family news and reading material. They developed a collaborative rapport also in artistic matters. John sent sketches [Fig. 7] and bounced off ideas for paintings with William.42 William advised which picturesque corners of the Thames would be suitable for pictures, suggested changes and retouches and supplied John with photographs of landscapes.43

Fig. 7: John Linnell, sketch for a picture, ink and wash on paper, source: John Linnell Archive, Fitzwilliam Museum.

Creative Commons Licence.

In 1863 William commissioned Linnell a painting for his own personal collection; from this request we know what William found particularly appealing in John’s paintings: his broad panoramic views that reflected the beauty and moral qualities of nature and, especially, his sunsets. As William wrote:

“Now I am going to commit an extravagance perhaps for myself. I am going about to ask you to paint one of similar size for my ‘alter ego’, anyhow, for my private self and leave its subject entirely to yourself only observing that I always like ‘loads’ of distance, that I like to escape behind the canvas and I dislike to be shut in and that a sunset to me is an impressive charm and a solemn teaching.”44

Sometimes William did not like some details of a painting and asked for changes. Even in these cases the tone of their correspondence is warm and affectionate. In November 1863, John responded to William’s expressed dislike of the choice of cows in one of his pictures – William had suggested that John should paint sheep instead. The exchange gives an idea of the witty tone and the rapport between the two:

“My Dear Sir,

If you were going to dine with a friend who had promised you to have some of the best beef he could procure for dinner, would you be satisfied if when he found that you preferred mutton he took care to have a saddle at one end of the table besides the beef? You would not require him to discard the beef altogether, I guess? Just so I have anticipated your satisfaction with my plan of meeting your wishes in the new kitcat by introducing a flock of sheep along with the cows which you object to. I should spoil my spread if I did not admit the beef – and the mutton I think it is an improvement as a variety with the beef - so please to let me know at your convenience if this arrangement will suit your palate as well as my palette.”45

William’s intervention into the very heart of the compositional elements of a painting has so far received merely a literal explanation. In his study of Linnell, Firestone posited, somewhat tautologically, that this request of a sheep was because “William Agnew liked pictures of sheep”.46 This observation is inaccurate as well as simplistic: there were plenty of cattle paintings available in Agnew’s stock by artists like Henry William Banks Davis, Thomas Sidney Cooper and Keeley Halswelle, who had made cows their speciality.47 I argue, instead, that this is an example of William’s deep engagement with the visual motifs in John Linnell’s art, as Linnell used sheep in a particularly skilful manner. He painted them as blots of creamy white to streamline panoramas and vistas, create composition lines and also to present a visual equivalent to the clouds in the sky [Figure 8]. William Agnew’s exhortation to Linnell to use sheep instead of cows indicates an understanding of what was distinctive and visually persuasive in Linnell’s style and composition and demonstrates the depth of their artistic relationship.

From 1871 onwards the correspondence between William and John ceased, and Linnell sold his work exclusively to the dealer Edward Fox White.48 The Agnew/Linnell correspondence does not reveal the details on how the two friends went on their separate ways, but there are many clues, starting in 1867–1868, of a deepening rift between them. The divergence has, again, been framed by Firestone strictly on business terms.49 The evidence presented by the correspondence and existing sales data, however, is more complicated, and shows a combination of personal disagreements, financial matters and artistic direction. Around 1867, according to John Linnell, William had begun to neglect his family’s friendship and his visits to Redhill had become less frequent. This created a new climate of personal resentment among the two friends.

John also suspected that William may be speculating on his pictures.50 William was adamant that this was not true.51 In fact Agnew’s profit margins for Linnell as recorded in his firm’s stock books did not change in the period 1861 to 1868. For example, in April 1868 Agnew’s purchased from Linnell English Woodlands from Linnell for £1,200. This high price was determined by Linnell on the wake of the success that another picture of his, A Harvest, had at auction in February 1868.52 Linnell’s gamble paid off: Agnew’s sold English Woodlands for £1,575 to William Mair, accruing a 31.25% net profit margin [Fig. 9].53 This profit however was consistent with Agnew’s early 1860s commissions on Linnell’s pictures, which ranged from 35% to over 50%.

Fig. 8: John Linnell, Contemplation, Oil on Canvas, 1864-5 (London, Tate Britain).

Creative Commons Licence.

Moreover, an analysis of the firm’s stock books reveals that, although Linnell’s paintings often carried good profits, he was not a principal source of earnings for Agnew’s. Other artists such as J.W.M. Turner, William Collins, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Thomas Faed, and Clarkson Frederick Stanfield were regularly being bought and sold on by Agnew’s for prices higher than Linnell’s.54

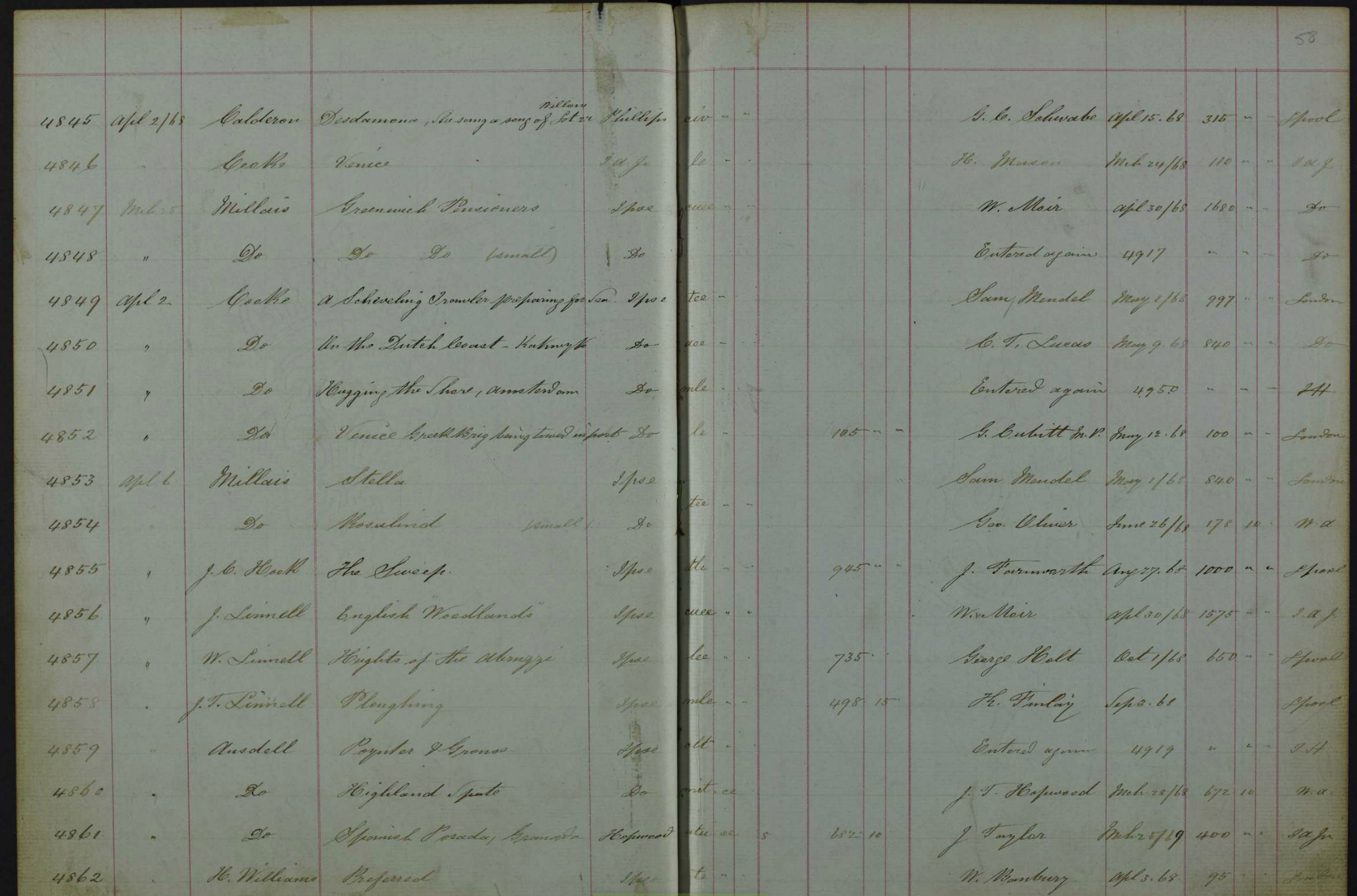

Figure 9 Page from Agnew’s Stock Book Volume 1A fol. 52, London, National Gallery Archive. Creative Commons Licence.

Firestone stated that in the late 1860s Agnew’s baulked at Linnell’s prices and wanted to get out of dealing in these before the market for them crashed.55 In point of fact, the market for this master remained healthy throughout the decade. Prices of works by Linnell, from his early to late period, continued to raise for the five years immediately after Agnew’s ceased to deal directly with the artist; in the period 1866 to 1870 the average auction price for Linnell’s work was £722 and this rose to £1,013 for the years 1871 to 1875.56

I contend that the separation between William and John rested, as well as on pricing and personal circumstances, on artistic matters: David Linnell had already noted that William Agnew, as reported by the dealer Fox White, openly criticised John Linnell’s post-1868 work finding it “sloppy” and “unfinished”.57 Agnew’s later purchases of works by Linnell also corroborate this: William continued to buy Linnells at auction for his stock, for instance in 1872 he bought The Woodlands for the record price of £2,625, but his purchases were exclusively concentrated on Linnell’s output from the 1830s until the late 1860s.58 If William Agnew had been merely a commercially-minded, entrepreneurial businessman he would have continued to buy works by Linnell and sold them at a good profit, as the dealer Fox White did from 1871 onwards.59 But Agnew ceased to agree with Linnell’s artistic production and therefore he did not purchase from this artist any longer.

This case study has highlighted two methodological guidelines to investigate the artist/dealer relationship.

Firstly, the necessity to place this relationship within the broader context of the market in which dealers and artists operate. This is because market conditions have an impact on the power dynamics between makers and mediators. In this case, Linnell operated in a bullish market with a high demand for landscape painting, and therefore he negotiated from a position of greater strength, not only because he represented a relatively risk-free investment for Agnew, but also because, as an artist in demand, he could choose between the many dealers who wanted to sell his paintings. Linnell could thus determine freely his own prices and his own conditions of trade. This explains the financial confidence, the entrepreneurial manner with which he could behave.

Secondly, the necessity to triangulate correspondence between artists and dealers with other forms of evidence such as financial records. This is because letters may fashion a self-framing narrative and disguise the other motives of artist and dealers alike. In this case, the Agnew’s Stock Books and data from Christie’s auction catalogues demonstrate Agnew’s unstinting support of Linnell’s work until 1871.

The principal contribution of this article has been to bring fresh evidence to the argument that aesthetic impulse and commercial acumen – what Jensen dubbed the ideological and the entrepreneurial discourses – can be simultaneously present in the artists’ and the dealers’ modus operandi, and that already existed in an established form in Victorian times. Artists may be skilled business people and, conversely, art dealers too may possess artistic sense and integrity; a point that has already been made for contemporary art dealers by sociologist Velthuis and that has also been noted for aesthetic businesses by theorist of fashion Joanna Entwistle.60 As she writes, to consider businesses such as fashion houses (or, I contend, art dealers) only in terms of economic categories, like profit and loss, “would fail to capture the particular ways in which they secure economic success and what makes them tick as businesses”; in Entwistle’s definition, aesthetics reflects not to “some abstract realm of beauty, but [to] the precise way in which things are inflected or articulated with aesthetic qualities that are important and, in some businesses, essential, to company success”.61 In this article, I too have argued for this inflection and articulation, demonstrating how Agnew’s commercial decisions were based on an aesthetic judgment which was, in turn, informed by commercial considerations.

The combination of aesthetic impulses and commercial acumen will, of course, present varying degrees according to the different artists and dealers and to the changing historical circumstances. Perhaps, then, one of the most crucial tasks for the historians of the art market is to be particularly attentive to this dynamic and multidirectional aspect of the discipline; namely the presence of the “art” and “market” element in the art trade, and their complicated coexistence.

Acknowledgements: I wish to thank Susanne Meyer-Abich and the anonymous readers for the Journal for Art Market Studies whose reviews have contributed to strengthen my text. I am also grateful to Johannes Nathan, Bénédicte Savoy and Dorothee Wimmer, organisers of the 2015 workshop on “Artists on the Market” for the Forum Kunst und Markt in Berlin, where I had the opportunity to present a paper from which this article originated.

Barbara Pezzini has recently completed her doctorate at the National Gallery/University of Manchester and is Editor-in-Chief of the academic journal Visual Resources.

1 [Anonymous], The Times (21 January 1882), 9. John Linnell was an important artist, obituaries were also published in The Athenaeum, The Academy, The Architect, Building News, The Builder and The Manchester Guardian; see Index of Obituary Notices 1880-1882 (London: The Index Society, 1883), 64.

2 This is for me a returning interest – I have treated aspects of the relationship between the market and artistic production for the period 1890–1914 in Barbara Pezzini, The 1912 Futurist Exhibition at the Sackville Gallery, London: an Avant-Garde Show within the Old-Masters Trade, in The Burlington Magazine 155 (July 2013), 471–479; Barbara Pezzini, New Documents Regarding the 1902 ‘Fans and Other Paintings on Silk by Charles Conder’ Exhibition at the Carfax Gallery, in The British Art Journal 13 (Autumn 2012), 19–29 and especially Barbara Pezzini, (Inter)national Art: the London Old Master Market and Modern British Painting, in Art Crossing Borders: The Birth of an Integrated Art Market, edited by Jan Dirk Baetens and Dries Lyna (Brill, Leiden, forthcoming, 2018).

3 Many examples noted by Pamela Fletcher, Creating the French Gallery: Ernest Gambart and the Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery in Mid-Victorian London,in Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide, 6/1 (2007), online.

4 For Moore’s biography, see Edwin Gilcher, Moore, George Augustus, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), online.

5 George Moore, Modern Painting (London: Scott, 1893), 153-154.

6 On the modernist reference to art as hallowed object, see Kate Flint, Moral Judgement and the Language of English Art Criticism 1870–1910, in Oxford Art Journal 6 (1983), 62–63.

7 Grischka Petri, Arrangement in Business. The Art Market and Career of James McNeill Whistler (Hildesheim, Zurich and New York: Olms, 2011), 149–248. Julie Codell, The Art Press and the Art Market: The Artist as ‘Economic Man’, in Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich, eds., The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London 1850–1939 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), 128–150.

8 See for instance, Mark Westgarth, Florid Speculators in Art and Virtu: the London Picture Trade c. 1850, in Fletcher and Helmreich, The Rise, 26–46; Anne Helmreich, The Global: Goupil & Cie/Boussod, Valadon & Cie and International Networks, in Anne Helmreich and Pamela Fletcher, Local/Global: Mapping Nineteenth–Century London’s Art Market, Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide, 11/3 (2012), online; Anne Helmreich, David Croal Thomson: The Professionalization of Art Dealing in an Expanding Field, Getty Research Journal 5 (2013), 89–100; Agnès Penot, The Perils and Perks of Trading Art Overseas: Goupil’s New York Branch, Nineteenth Century Art Worldwide, 16/1 (2017), online.

9 Pamela Fletcher, Shopping for Art: the Rise of the Commercial Gallery, 1850s–90s, in Fletcher and Helmreich, The Rise, 47–54; Pamela Fletcher, The Grand Tour on Bond Street: Cosmopolitanism and the Commercial Art Gallery in Victorian London, Visual Culture in Britain, 12/2 (2011), 139–153; see also Christian Huemer, Crossing Thresholds: The Hybrid Identity of Late Nineteenth-Century Art Dealers, in Jaynie Anderson, ed. Crossing Cultures: Conflict – Migration - Convergence (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press 2009), 1007–1010. The dichotomy between shop and gallery continued until the Edwardian period at least, see Samuel Shaw, The New Ideal Shop: Founding the Carfax Gallery, c. 1898-1902, in The British Art Journal, 13 (Autumn 2012), 35–43.

10 Raymonde Moulin, The French Art Market. A Sociological View [1967] (New Brunswick and London: Rutgers, 1987), 58–59.

11 Moulin, The French Art Market, 58.

12 Robert Jensen, Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press 1997), 53–54.

13 Poppy Sfakianaki, Promoting the Value(s) of Modernism: The Interviews of Tériade and Zervos with Art Dealers in Cahiers d’Art, 1927, Visual Resources, 31 1/2 (2015), 75–90; Giovanni Casini, Gino Severini e Léonce Rosenberg: uno Scambio Commerciale e Intellettuale per la Difesa dell’Arte Moderna, 1917-21, Ricerche di Storia dell’Arte 121 (2017), 29–36.

14 Pierre Bourdieu, The Social Structures of the Economy [2000] (Cambridge: Polity, 2005), 205. I extensively discussed Bourdieu’s position in Barbara Pezzini, Making a Market for Art, Agnew’s and the National Gallery 1855-1928, PhD Thesis, The National Gallery/University of Manchester 2017, 41–73. The thesis is freely available (https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/67403312/FULL_TEXT.PDF).

15 Viviana A Zelizer, Circuits of Commerce, in Jeffrey C. Alexander et al., eds., Self, Social Structure and Beliefs (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 121–144; Viviana A. Zelizer, “Culture and Consumption,” in Neil J. Smelser and Richard Swedenberg, eds., The Handbook of Economic Sociology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 331–354; Olav Velthuis, Talking Prices [2005] (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007); Olav Velthuis, Circuits of commerce, in Jens Beckert and Milan Zafirovski, eds., International Encyclopedia of Economic Sociology (London: Routledge, 2006), 57–58; Pezzini, Making a Market for Art, 41–73.

16 For William Agnew and Manchester, see Dianne Sachko MacLeod, Art and the Victorian Middle Class: Money and the Making of Cultural Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), esp. 100; Dongho Chun, Art Dealing in Nineteenth-Century England: The Case of Thomas Agnew, in Horizons 2 (2011), 255–277; Pezzini, Making a Market for Art, esp. 74–87.

17 Thomas M. Bayer and John R. Page, The Development of the Art Market in England: Money as Muse 1730-1900 (London: Pickering & Chatto 2011), 99–100.

18 Bayer and Page, The Development, 102–103.

19 Gerard Reitlinger, The Economics of Taste. The Rise and Fall of Picture Prices, 1760–1960 (London: Barrie and Rockliff 1961), 143–170; Bayer and Page, The Development, 99–118.

20 Reitlinger, The Economics of Taste, 143. Anne Helmreich and Pamela Fletcher, The Periodical and the Art Market: Investigating the ‘Dealer-Critic System’ in Victorian England, in Victorian Periodicals Review 41 (Winter 2008), 323–351.

21 On these artists, see Petri, Arrangement, 149–248; Malcom Warner, Millais in the Marketplace: The Crisis of the Late 1850s; Brenda Rix, Branding the Vision: William Holman Hunt and the Victorian Art Market; Patricia de Montfort, Negotiating a Reputation: J.M. Whistler, D. G. Rossetti and the Art Market 1860–1900, all in Fletcher and Helmreich, The Rise, respectively, 216–236; 236–256; 257–275.

22 For Linnell’s biography, see Alfred Thomas Story, The Life of John Linnell, 2 vols. (London: Richard Bentley and Sons, 1892); William Cosmo Monkhouse, Linnell, John, in Dictionary of National Biography 1885-1900, vol.33 (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1893): 329-331; more recently, David Linnell, Blake, Palmer, Linnell and Co: the Life of John Linnell (London: Guild Books, 1994); Christiana Payne, Linnell, John (1792–1882)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2004), online. Linnell’s paintings are recorded in Landscape and Portrait Sketchbooks, British Museum Archive, 1976-1-31-6/7.

23 Story, The Life of John Linnell, vol.1, 1–26.

24 Story, The Life of John Linnell, vol.2, 5.

25 A copy of the “Dialogue upon Art” [MS415-2000] is preserved in the John Linnell Archive, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (hereafter cited as JLA); Story, The Life of John Linnell, vol.2, 58–59.

26 Christiana Payne, John Linnell and Samuel Palmer in the 1820s, in Burlington Magazine 124 (1982), 131–136.

27 On Agnew’s, [Geoffrey Agnew] Agnew’s 1817-1967 (London: Agnew’s, 1967), hereafter cited as Agnew’s; Chun, “Art Dealing”, 255-277; Dennis Farr, Agnew family, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), online; Oliver Garnett, Agnew, Thos, & Sons, in Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), online.

28 Agnew’s, 19, 45–56.

29 Agnew’s began to sell to Lionel de Rothschild in May 1869. A Portrait of Miss Leigh (Lloyd) by Reynolds bought at Christie’s on 29 May 1869 for £640 was sold to him for £1,500, Agnew’s Stock Book 1A no.5444 [NGA27/1/1/3] National Gallery Archive (hereafter cited as NGA). Sales continued in the course of the 1870s, for instance a Miss A. Ford by Gainsborough on 2 April 1870, ASB1A no.5721. American banker and financier Junius Spencer Morgan (father of John Pierpont Morgan) began to purchase works from Agnew’s in the early 1870s; for example, he bought The Reapers by Thomas Faed on 29 April 1872 for £1,680, Agnew’s Stock Book 2 no.6880 [NGA27/1/1/4], NGA.

30 Farr, Agnew Family, reports the wealth at death of Thomas Agnew as under £80,000 (probate, 24 May 1871), and William Agnew £1,353,592 10s. 8d. (probate, 1911), both CGPLA Eng. & Wales.

31 The connections of the Agnew family with contemporary British artists have not yet been explored in full; see the Artists Associated with Agnew’s File, 1873–1901 [NGA27/24/1] and [NGA27/32/2-3], NGA; John George Marks, Life and Letters by Frederick Walker (London: Macmillan, 1896), passim but especially 48–84.

32 Richard Lines, A History of the Swedenborg Society 1810-2010 (London: Lulu, 2012), 3-17. The Agnews were also known philanthropists, see William E. A. Axon, Annals of Manchester (Manchester: Heywood, 1886), 327; on Salford museum, see Ben H. Mullen, Salford and the Inauguration of the Public Free Libraries Movement together with A Short History of the Museum and Libraries (Salford: Jackson, 1899).

33 Pezzini, Thomas Agnew and the Rise of the Civic Dealer, in ‘Making a Market for Art’, 77–87.

34 Jonathan Bayley, Mr. Agnew and Cheap Day Schools in Manchester, Salford, and the North, in New Church Worthies (London: Speirs, 1884), 36–41.

35 Axon, Annals, 327; Mullen, Salford, 4–12; Agnew’s, 10–15.

36 Visitor figures in: Salford Museum Annual Report (Salford 1860–1861), 4–5. Thomas Agnew’s activities as Salford councillor are recorded by the Manchester Guardian, for instance “Salford Council”, 14 September 1850, 8; 20 November 1850, 6; 12 November 1851, 3; 23 June 1852, 3; 12 November 1853, 8.

37 William Roberts, Agnew, William, in The Dictionary of National Biography, Second Supplement (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1912), 22-24; see also, Agnew, Sir William, Who Was Who (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), online. For his political career, Pezzini, William Agnew: Liberal Politics and Old Masters Trade, in ‘Making a Market for Art’, 136–147.

38 Evan R. Firestone, John Linnell and the Picture Merchants, in The Connoisseur 182 (1973), 124–131.

39 30 April 1853, John Linnell to Thomas Agnew [MS 6945 2000], JLA. This transaction is not listed in the earliest extant Agnew’s stock book 1*, 1853-1861 because direct sales from artists do not seem to be recorded there. The Linnell pictures that Agnew’s purchased from dealers in 1853 were priced around £250-350, hence Thomas Agnew’s surprise in the letter to be asked over £500 from the artist, see [NGA27/1/1/1], NGA. Algernon Graves, Art Sales (London: Graves, 1921), vol.2, 164, first notes Agnew’s as purchasers of Linnell in 1851.

40 6 September 1859, John Linnell to William Agnew [MS 6946 2000], JLA. Also cited by Linnell, Blake, Palmer, Linnell and Co, 282.

41 Calculations by the author from figures from the Agnew’s Stock Books [NGA27/1/1/2-NGA27/1/1/3], NGA.

42 For example, 26 January 1863, John Linnell to William Agnew, MS7347 2000 and 26 March 1864, [MS7424 2000], JLA; Story, The Life of John Linnell, vol.1, 55, had already noted Linnell’s excellent relationship with William Agnew, based on “sincere mutual respect”.

43 See for instance [MS 6962 2000]; [MS 6960 2000]; [MS 6959 2000]; [MS 6951 2000], JLA.

44 Undated, William Agnew to John Linnell, [MS7424 2000], JLA, also cited by Firestone, John Linnell, 127.

45 5 November 1863, John Linnell to William Agnew [MS7401 2000], JLA.

46 Firestone, John Linnell, 130.

47 For instance, see Agnew’s Stock Book 1*, nos. 2613, 2676, 2775, etc. [NGA27/1/1/2], NGA.

48 Letters between the Linnells and Fox White preserved in the JLA.

49 Firestone, John Linnell, 130.

50 12 November 1867, John Linnell to William Agnew [MS7576 2000], JLA.

51 14 November 1867, William Agnew to John Linnell [MS7599 2000], JLA

52 A Harvest sold for £1,055 on 22 February 1868. Graves, Art Sales, 166. The sale of this picture, defined “a splendid chef d’oeuvre” was advertised twice in Sales by Auction, in The Times (4 February 1868), 12 and (18 February 1868), 12.

53 Agnew’s Stock Book 1A, no. 4856 [NGA27/1/1/3], NGA.

54 See [NGA27/1/1/2], NGA.

55 Firestone, John Linnell, 130.

56 Graves, Art Sales, 166-167.

57 Linnell, Blake, Palmer, Linnell and Co, 332–333.

58 Graves, Art Sales, 167.

59 Graves, Art Sales, 167–168.

60 Velthuis, Talking Prices, 3–26. Joanna Entwistle, The Aesthetic Economy of Fashion: Markets and Value in Clothing and Modelling (Oxford: Berg, 2009), 26–29.

61 Entwistle, Aesthetic Economy, 28.