ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

A Review:

by Eleonora Vratskidou

While dOCUMENTA 13 (2012) reflected on the annihilation of cultural heritage, taking as a starting point the destruction of the two monumental Buddha statues in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, by the Taliban in 2001,1 the recent documenta 14 (2017) actively addressed the question of art theft and war spoliations, taking as its point of departure the highly controversial case of the Gurlitt art hoard. The circa 1,500 artworks uncovered in the possession of Cornelius Gurlitt (1934-2014), inherited from his father Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895-1956), one of the official art dealers of the Nazi regime, brought back to the surface aspects of a past that Germany is still in the process of coming to terms with.

Initially, the intention of artistic director Adam Szymczyk had been to showcase the then unseen Gurlitt estate in the Neue Galerie in Kassel as part of documenta 14. Revisiting the tensed discussions on the status of the witness with regard to the historical experience of the Holocaust (as addressed by Raul Hilberg, Dori Laub or Claude Lanzmann), Adam Szymczyk, in a conversation with the art historian Alexander Alberro and participant artists Hans Haacke and Maria Eichhorn, reflected on plundered art works as “witnessing objects”, which in their material and visual specificity are able to give testament to an act of barbarism almost inexpressible by means of language.2

Szymczyk’s initiative to make the Gurlitt cache available to view was also explicitly associated with the founding gesture of Arnold Bode (1900-1977), whose inaugural documenta back in 1955 had been largely conceived as an attempt to rehabilitate modern art deemed ‘degenerate’ under the National Socialist Regime.3 In 1955, documenta set itself the task to repair the violence committed against persecuted art. Sixty years later, this same institution was to resume and complete that task of self-scrutiny in exposing how the ideological devaluation of modern art in National Socialist Germany was combined with concrete economic benefits from its sales abroad, thanks to the efficient system of art looting devised by the Nazi administration, along with its systematic persecution and murder of people.

In the end, Szymczyk’s project to showcase the Gurlitt estate at documenta 14 did not materialise. Instead, two complementary exhibitions, organized by the German state, opened at the Kunstmuseum Bern and the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn in November 2017, barely two months after the end of documenta 14.4 In many ways, Szymczyk’s vision set a standard against which the two shows are to be measured.

Despite its absence, the Gurlitt case remained a haunting presence for the curatorial project of documenta 14 and operated as a central “organizing principle”5 particularly in the show at the Neue Galerie in Kassel. The history of this family of artists and art historians – an incarnation of the German Bildungsbürgertum – spanned four generations back to the nineteenth century, and formed a running thread through a highly intersected web linking Greek-German cultural relations since the late eighteenth century, the Enlightenment and the development of European colonialism, as well as the traumatic experience of the Second World War.

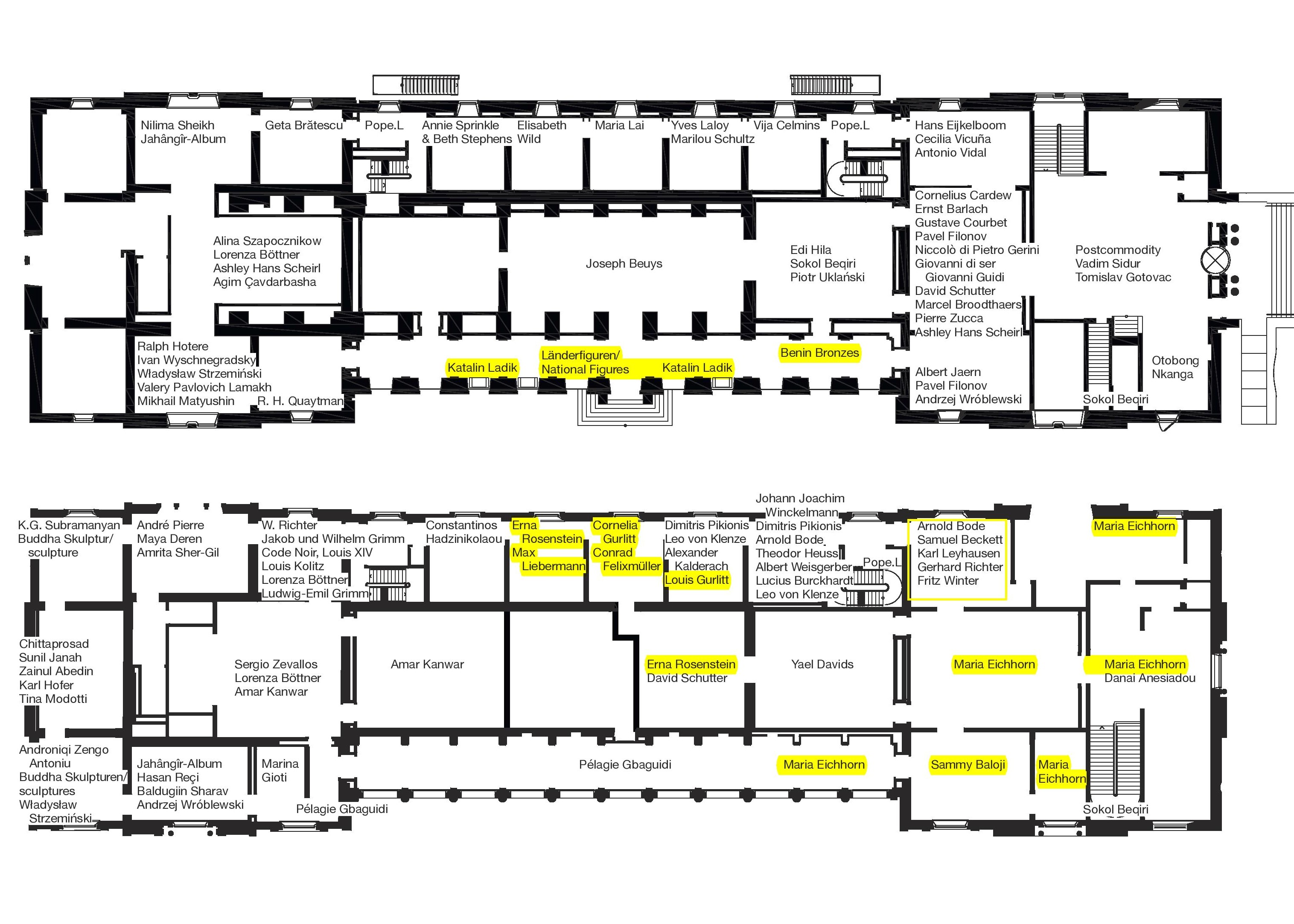

In the following, I will propose a reading of this curatorial construct deployed over the first half of the upper floor of the Neue Galerie (fig. 1), commenting in particular on its historiographical stakes. The curators of documenta chose to give historical depth to the Gurlitt case and to intertwine it with much larger narratives. In doing so, they succeeded in staging a multi-perspective account of complex historical situations, spanned by contradictory forces, disjuncture and overlapping timelines. I will subsequently look at a second constellation of works on the ground floor of the museum, figuring three of the so-called Benin bronzes – an iconic case of colonial seizure of cultural assets –, in order to reflect on the curatorial interest in juxtaposing fascist and colonial legacies, but also on the curatorial discrepancies regarding this latter case.

The first glimpse of the Gurlitt theme came in a room which did not immediately pertain to the Gurlitt narrative, but was rather devoted to the founding context of documenta, exploring the local realities in Kassel before and after the war, in connection with the global political and economic alliances of the Cold War that marked the inception of the institution.6 One of the exhibits in this room was the notebook of the Irish writer Samuel Beckett (1906-1989) from his journey through Nazi Germany in 1936-1937 “in search”, as observed in the caption, “of avant-garde art – which by then had of course been deemed ‘degenerate’”.7 The caption continued: “German museums no longer had the likes of Otto Dix, Oskar Kokoschka, or Max Liebermann on view, but there were luckily still enough private galleries trafficking in censored art, such as the one run by Hildebrand Gurlitt”.8 The document references a time in which the dealer didn’t yet work for Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda, pursuing rather his genuine engagement for the avant-garde that had cost him his position as a museum director in Zwickau back in 1932.9

Opposite to Beckett’s diary, the so-called “Monuments Men” entered the plot – that is, the Monuments, Fine Art and Archives Section of the American Military Government, who were in charge of recovering and restituting Nazi-plundered art. Hildebrand Gurlitt had managed to escape from this unit’s arrest and interrogation shortly after the war, dissimulating evidence and stressing his Jewish origins.10 The exhibit was a draft of their 1945 ‘Wiesbaden Manifesto’, a protest letter against spoliation of cultural assets as war booty, co-signed by twenty-five members of the Section. The choice of the document is interesting: this declaration was drafted not so much with regard to the excessive and systematic Nazi art theft from museums, libraries and private collections across Europe, but rather targeted what was viewed as abuses by the United States administration of art objects temporarily in American custody. The incident that triggered the manifesto, the transfer of recovered art objects to the United States,11 would indicate that liberators can easily turn into victimizers themselves.

Fig. 1: FloorplanPlan of ground and upper floor of Neue Galerie, Kassel, documenta 14 (screenshot from the documenta 14 online available map; annotations by the author)

The overall selection of archival documents exhibited in the room could be read as a reflection on historical turns on the contaminative nature of power abuse and on the vicious circles of dispossession, which questions fundamental dichotomies between victims and perpetrators, between the victorious and the vanquished.12 “This is the story of wheels within wheels”, as stated on the first page of another seminal historical document exhibited next to the Wiesbaden Manifesto: a preliminary report on the Buchenwald concentration camp written by Edward Tenenbaum and Egon Fleck. They had been the first Americans to enter the camp after the German retreat in April 1945, and described a terror that was multi-focal, driven by the Nazi administration and unfurling across rivalries between various groups of inmates.13 History was then staged as a set of overlapping power shifts and the focus on the circularity of violence elicited reflexivity rather than relativism.

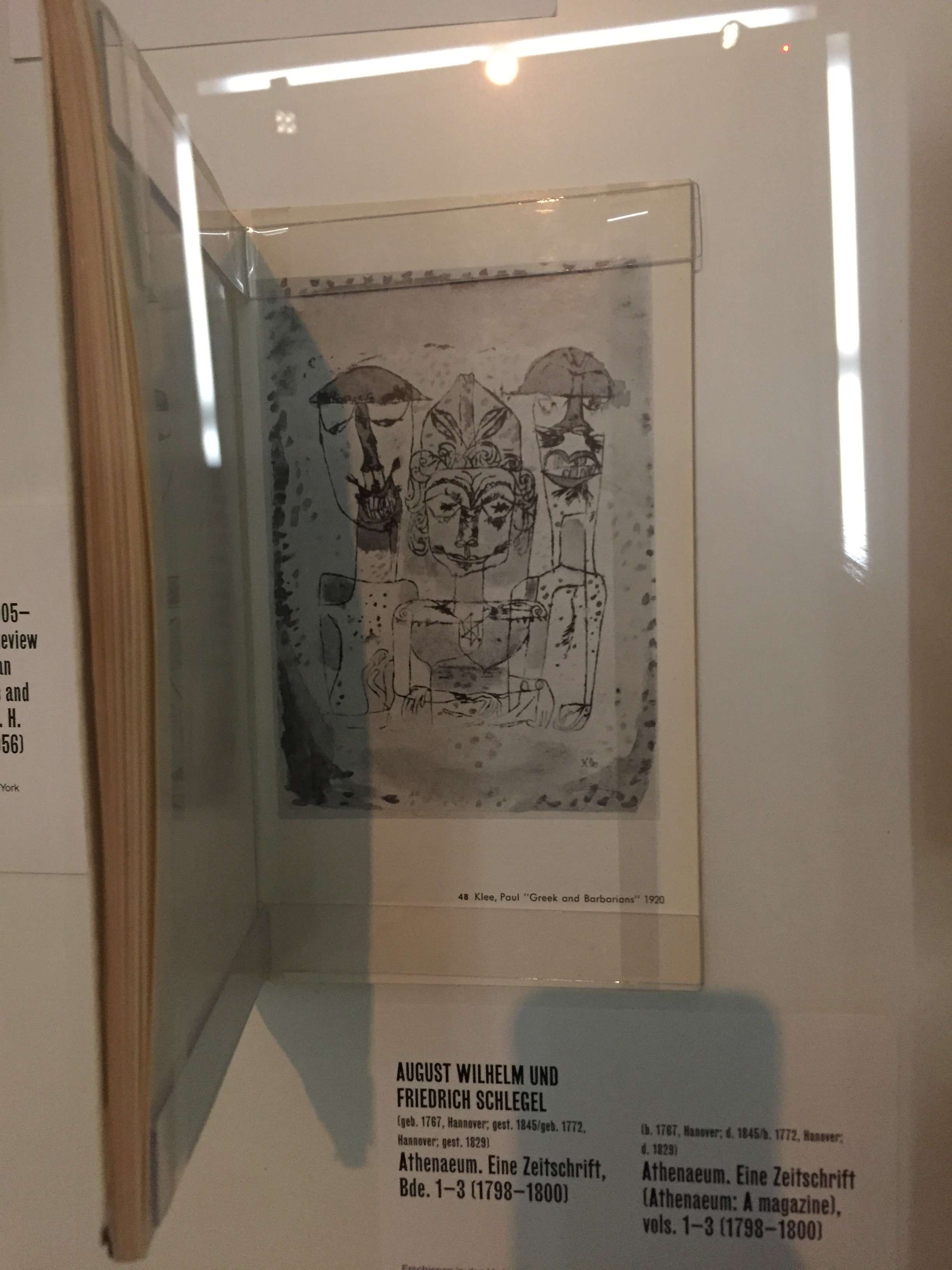

Fig. 2: Catalogue of the exhibition German watercolors, drawings and prints; a mid-century review, with loans from German museums and galleries and from the collection Dr. H. Gurlitt on display. Photo Eleonora Vratskidou.

This approach is also illustrated in an exhibit in the next room. Infiltrated into the group of the central vitrine documenting successive “rediscoveries” of Athens in modern times – from Jacob Spon’s, Relation de l’état présent de la ville d’Athènes, ancienne capitale de la Grèce of 1674 to Adolf von Schaden’s manual for Bavarian settlers in the newly founded Kingdom of Greece, reigned over by the Bavarian prince Otto von Wittelsbach (Der Bayer in Griechenland, ein Handbuch für Alle, welche nach Hellas zu ziehen gedenken, 1833)— was a slim book open at a page showing a reproduction of Paul Klee’s drawing, Greek and Barbarians (1920) (fig.2). This was the catalogue of the exhibition German watercolors, drawings and prints; a mid-century review, with loans from German museums and galleries and from the collection Dr. H. Gurlitt, a loan show which toured the United States in 1956, sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany as part of a systematic campaign to rehabilitate modern art and German Expressionism in particular, after its denigration during the Nazi era. As mentioned in the very title of the catalogue, Gurlitt himself figured as a major lender. Changing camps after the war, the dealer actively engaged in the young Republic’s cultural programme, inaugurated with the landmark exhibition of 1949, Der Blaue Reiter. München und die Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts.14 The presence of the catalogue among the exhibits silently testified to Gurlitt’s new volte-face. At the same time, this document, which referenced Gurlitt’s disquieting involvement in Germany’s cultural politics after the war, sealed within it multiple temporalities. Open at the page of Klee’s drawing – which pertained to the Greek theme of the room – the catalogue also alluded to the slur of “degeneracy” conferred upon the artist and the dubious circumstances under which the work entered Hildebrand Gurlitt’s collection in 1940 as well as to its 2014 bequest to the Kunstmuseum Bern by Cornelius Gurlitt. In the display, single objects were thus transformed into layered historical constructs.

After more or less direct allusions to Hildebrand Gurlitt within these constellations of works, the history of the family unfolded in greater detail in the following rooms, going back to the middle of the nineteenth century and to Louis Gurlitt (1812-1897), Hildebrand’s grandfather. In 1858 this landscape painter from Hamburg had travelled to Greece, then still under the rule of its Bavarian-born King. His exhibited Acropolis (1858) hung adjacent to Alexander Kalderach’s Parthenon dated 1939 – a painter who had his moment of glory in Hitler’s time. The narrative thus regained the National Socialist era, collapsing times of Germany’s persistent fascination with classical Greece.

The next room of the gallery was devoted to the graphic work of Cornelia Gurlitt (1890-1919), Hildebrand’s sister. “Well-versed in the angular language of German expressionism”, 15 Cornelia served as a nurse during the first World War and upon her return from the Eastern Front, committed suicide in 1919. As the caption suggestively observes, “she would not live to see her brother ascend to the heights of the Nazi art bureaucracy”. Her suicide mirrored that of Karl Leyhausen (1899-1931) that came up earlier in the room devoted to the inception of documenta. The pre-war artistic and intellectual context in Kassel was portrayed through the works of two central figures, Arnold Bode (1900-1977) and his close friend Karl Leyhausen, a painter and art critic, leading member of the Kassel Secession. Leyhausen took his own life in 1931, leaving a note cited in the accompanying caption: “I know today more than ever how outrageously beautiful the gift of life is [...] and I am not throwing it away foolishly, but rather it is taken from me. A thoughtless, barbaric time has begun.”16 Unlike Karl Leyhausen and Cornelia Gurlitt, Arnold Bode and Hildebrand Gurlitt would survive the war – the first to become the founder of a major contemporary art venue created to repair the damage produced by the National Socialist regime; the second, pursuing his activity unabatedly as an art dealer and as director of the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen while also participating in the reinstatement of modern art both as a private collector and major exhibition lender. Drawing subtle connecting lines, the curatorial discourse shrewdly traced Bode’s and Gurlitt’s trajectories as examples of major continuities and breaks in German cultural history after the war. The artful interweaving of narratives based on associations rather than linear modes, inflating and deflating time like the bellows of an accordion, while eschewing grandiloquent or didactic rhetoric17 forms an essential quality of the display in this part of the show.

The haunting theme of Hildebrand Gurlitt’s activities under the Nazi regime resurfaced with David Schutter’s works, after drawings by Max Liebermann found in the Gurlitt trove,18 as well as with the paintings of Erna Rosenstein (1913-2004), a Jewish artist of Polish origin, victim and witness of Nazi persecutions. Her exhibited work The Looters (1948 and 1952) offers a rare iconographical instance of plundering. Portraits of her parents as decapitated 19 – they were murdered in 1942 in a failed attempt to flee persecution – were exhibited next to Riders on the Beach by Max Liebermann, himself a persecuted artist. The caption read: “Liebermann painted dozens of variations on the motif of the rider (or riders) on the beach, and he regularly crossed paths with art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt, who bought and sold Liebermann paintings throughout the Third Reich’s twelve years of existence –in transactions with varying degrees of legality. One such Two Riders on the Beach, dating from 1901, was found in Cornelius Gurlitt’s apartment in Munich in February 2012. It was returned to the heir of its rightful owner in 2015 and has since been sold off.”20 Scymczyk’s intention had been to showcase the Gurlitt estate in its entirety as a “political fact” and as a “material embodiment” of history before its dispersal.21 The reference to the sale of the Liebermann in the caption suggests that the integrity of this historical group of artworks is already dissolving.

The intertwined stories addressed above culminated –as in an instance of reparation – in Maria Eichhorn’s project The Rose Valland Institute, which was installed in a sequence of rooms in the exhibition. Named after the French art historian who secretly recorded information on Nazi looting during the German occupation of Paris and contributed significantly to the restitution of Jewish art property after the war, this large-scale, interdisciplinary ‘artistic research’ project on the expropriation of Europe’s Jewish population investigates issues of “unresolved property and ownership relationships from 1933 to the present day”, not only in Germany but also in Nazi-occupied France and other territories. Inaugurated through an open call on Unlawful Ownership in Germany, the project consisted of nine parts, including a research workshop, displays of extensive archival material documenting particular cases of plundered artworks and other property, an overwhelming 720-minute video projection of German auction records from the period 1935-1942, a reading room, and a towering shelf of books from Jewish ownership, unlawfully acquired by the Berliner Stadtbibliothek in 1943.

Maria Eichhorn meticulously applies methodologies of provenance research in her artistic practice, expanding on a tradition that refers back to Hans Haacke’s Manet-PROJEKT’74 (1974), a landmark of institutional critique.22 What is new and particularly interesting in the Rose Valland Institute, is the expansion of the research field to Nazi expropriations in the occupied territories, and, more importantly, the fact that the focus is no longer primarily on artworks or art objects. The investigation encompasses all kinds of assets: land, real estate, businesses, movable objects and artefacts, libraries, even academic work and patents.23 Mobile objects included are books from a public lending library, all kinds of furniture and clothing, a bed, a chair, a woman’s purse. These have circulated in and out of private homes, were inherited, handed down and marked everyday life, weaving traces of an old crime into the fabric of the physical and social environment for generations. Shifting the focus away from state-run institutions and politics, this private dimension of the investigation revisits in the most sweeping way questions of complicity and collective responsibility regarding the Holocaust. The open call that inaugurated the project summoned everyone who might be in procession of looted goods to enter a process of self-scrutiny and restorative agency, thus reversing the direction of restitution politics as we know it today24 and encouraging private initiative beyond the often rigid frameworks provided at government level.

The outcome and the sustainability of this documenta 14-launched project remains to be seen. Undoubtedly, Maria Eichhorn’s status as an internationally acclaimed artist and the stature of the exhibition reinforce the appeal that such an initiative may have both to the public and the relevant authorities. A major question remains with regard to the artistic specificity – both in terms of means and in terms of effects – of Eichhorn’s practices in this work, particularly given the fact that for the artist, the Rose Valland Institute should ideally become attached to an academic environment.25

The intention to draw parallels between Nazi and colonial era legacies of dispossession is evident in a room engulfed in Eichhorn’s exhibition-within-the-exhibition, displaying an installation by Sammy Baloji, Fragments of interlaced Dialogues (2017). Baloji’s work critically engages with the long history of colonial expropriations in Congo and its lasting effects today. In Baloji’s tight multi-temporal structure of enmeshed narratives, expropriation and exploitation were not simply attributed to the external Portuguese or Belgian colonizers. Instead, a process of self-colonization was addressed: an exhibited letter from King Afonso I of Kongo to the King of Portugal, dated 1514, proudly relates how in his efforts to catholicize the country Afonso had burned the Great House of Idols with its traditional power figures in the form of wooden statuettes.26 Written in perfect Portuguese, this exquisite piece of calligraphy illustrated another “story of wheels between wheels”. As a testimony to a successful appropriation of the European Other, it signalled the multiple layers of power involved in the process of colonization beyond unambiguous narratives.

The subject of contested colonial seizures resurfaced on the ground floor of the gallery. Three bronze sculptures from Benin were presented in the left-wing loggia along with a short text that recounted the story of the destruction of the Benin Kingdom, in today’s Nigeria, and the massive plundering of cultural assets from the Royal Palace in Benin City during the punitive expedition of 1897 by the British colonial forces.27 As the caption explained, an estimate of 3,500-5,000 artefacts were on this occasion sent to the British Museum or sold further to cover war expenses, resulting in their wide dispersal across public and private collections around the globe. Items of this group of artefacts have increasingly become objects of investigation, exhibition and restitution claims over the last twenty years.28

To my knowledge, this is the first time that such objects have been presented as part of a contemporary art exhibition. The two Benin head and a relief plate made of brass, dated from the eighteenth and nineteenth century, were juxtaposed with a coeval group of eight female marble figures representing the most prominent art nations in Europe, by the German sculptor Carl Echtermeier (1845-1910), and alongside the collages and sound installation by the Hungarian poet and performance artist Katalin Ladik (1942-), one of the leading figures of the Yugoslavian neo-avant-garde in the 1970s (fig.5).

Fig. 3: A king’s head from Benin, erroneously captioned as an “a queen mother, uhumnw-ealo (Edo, Benin Empire, ca. second half of the nineteenth century)”. Screenshot from documenta 14 website (http://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/22790/benin-bronzes)

Conceived for the monumental staircase of the gallery upon its construction in the 1870s, Carl Echtermeier’s allegorical sculptures personify ancient Greece, ancient Rome, Italy, France, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands and England (Länderfiguren, 1876-1882).29 The curators of documenta 14 chose to engage directly with this newly restored group from the permanent collections of the Neue Galerie,30 with the express intention to address “histories of exclusion, fallacies of canonization, narratives of dispossession and colonial legacies”31. In this oblong room, the crowned queens embodying the European “Kulturnationen” encountered on an equal footing Katalin Ladik’s Queen of Sheba32 – the biblical Queen of the South – and a queen mother from Benin (fig. 3). The display runs counter to the historical capacity of the space as a galleria progressiva.

As stated in the short text on the curatorial concept of the Neue Galerie, the opening of the museum, designed to house the Old Masters collection of the Hessian landgraves, “coincided with the heady early days of the German empire. Its phalanx of eight marble Länderfiguren in particular [...] speaks to the entanglement of nationhood, institution building, and cultural politics in this triumphant moment soon after modern Germany’s emergence from the Franco-Prussian War”.33 In combination with an impressive cycle of wall paintings by Carl Gottlieb Merkel (1817-1897),34 the sculptural display of the museum framed the presentation of the actual artworks with a figurative art history, a set of visual narratives on the major art schools and leading masters, illuminating the ideals and dominant categories of a thriving art history, a major institution of cultural politics during the German Empire. Curiously, instead of revisiting this institutional framework of knowledge-power production in the accompanying caption, the group was presented as an isolated work conceived upon the artist’s initiative: “From 1876 to 1882, the German sculptor Carl Friedrich Echtermeier (1845-1910) took upon himself the duty of producing a series of sculptures entitled “Länderfiguren” (National figures) [...] Echtermeier’s attempt was to create the canon par excellence. What Echtermeier left out of his equation was the arts of the so-called ‘rest of the world’”.35

Fig. 4: Figurines from Benin on display at documenta 14. Photograph Eleonora Vratskidou.

The arts of the “rest of the world” are what the curators of documenta 14 sought to bring back into the picture through presenting the artefacts from Benin. In addition, Katalin Ladik’s visual scores accompanied by sound recordings echoed the voices of political and cultural entities “that no longer exist or have been excluded from the proposed art history”,36 such as the former Yugoslavia, the German Democratic Republic, Poland or the Balkan countries.37 The interest of this juxtaposition lies not simply in the revision or expansion of established canons but mainly in the exposure of and challenge to the very grounding categories and principles of canon-making. Carl Echtermeier’s sculptures carved from Carrara marble perfectly convey the fixity of the category of the “nation” imposed upon the humanities as a taxonomic framework during his time. Personifying national artistic cultures as distinct, self-contained entities, the figures silence the multitude of transfers, transnational entanglements and crossbreeding upon which (art) history is actually built.

Their monolithic character was however splendidly undermined by the works of Katalin Ladik. Ladik’s entire artistic practice revolves around notions of movement and transformation.38 The hybrid character of her practice is evident in her compositions moving across media, with collages functioning as graphic scores that give way to oral and bodily performances; in her fascinating experimentations on sound and the limits of language; or, on a different level, in her civic engagement in cultural dialogue in the multilingual and politically sensitive context of her native Vojvodina region in the former Yugoslavia.39 Placed between or across from Echtermeier’s sculptures (fig. 4), Ladik’s works occupied the interstitial, the in-between spaces of the gallery, as they do in art history writing. At the same time, they activated a contrapuntal mode, turning the gallery itself into a music score that needs “to be listened to ‘horizontally’ (as opposed to the ‘vertical’ listening implied by monodic and harmonic composition)”.40

Although the caption for the Benin bronzes sketched the context of their plunder, there was no reference to the provenance of the three exhibited figurines and to how they came to the Museum Fünf Kontinente, from which they were loaned for the show. Moreover, the caption dated the plundered items extracted during the punitive expedition by the British between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries,41 while the exhibited works were dated between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This could potentially have implied a different provenance for them, not necessarily linked to the violent incidents of 1897.42 While Maria Eichhorn intensely engaged provenance issues with utmost documentational rigour on the upper floor, the same question was neglected in the concrete case of ethnographic objects involving colonial collection practices. The principles expounded by the Rose Valland Institute, with its acute sensibility in terms of transparency, seemed to fade here, revealing the unequal treatment of western European art objects and extra-European artefacts and, ultimately, the very inertia with which the show wished to take issue. One can fully embrace the curatorial engagement in revising exclusive Western canons of art history. However, this revision – an exemplary horizontal take on an integrative art history – was accomplished by means of objects of colonial appropriation. In such instances, the critical reflexive turn of Western art history upon its canonical self stumbles abruptly against the violence of looting and dispossession often inflicted in the name of scientific ideals and accumulation of knowledge, leading to yet another “story of wheels within wheels”.

Fig.5: Ladik’s works occupied the in-between spaces of the gallery.

Photograph Eleonora Vratskidou

Eleonora Vratskidou is visiting professor at the Institute for Modern Art History at Technische Universität Berlin.

1 See mainly the text by artistic director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, On the Destruction of Art —or Conflict and Art, or Trauma and the Art of Healing, and the postcript to it, Dario Gamboni’s article World Heritage: Shield or Target, in the exhibition catalogue edited by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev and Katrin Sauerländer, The Book of Books (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012), 282-295, as well as the commissioned project by Michael Rakowitz, What Dust Will Rise (2012).

2 The Indelible Presence of the Gurlitt Estate: Adam Szymczyk in conversation with Alexander Alberro, Maria Eichhorn, and Hans Haacke, in South as a State of Mind, 6 [documenta 14: 1] (2015), 95-96.

3 The Indelible Presence, 95, 99.

4 Under the shared title Bestandsaufnahme Gurlitt/Gurlitt Status Report, the exhibitions explored different thematic foci: the exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Bern (2 November 2017 - 4 March 2018) was subtitled Entartete Kunst – Beschlagnahmt und verkauft, the one at the Bundeskunsthalle Bonn (3 November 2017 - 11 March 2018) Der NS-Kunstraub und die Folgen. A sequel is planned to open in Berlin in September 2018.

5 “Neue Galerie,” documenta 14, http://www.documenta14.de/en/venues/21726/neue-galerie (accessed 28 March 2018).

6 The post-war reconstruction of Europe, and of Germany in particular, aided by the Marshall plan, evoked through a series of posters on the wall, intersected, for instance, with developments in the Third World, such as the famous Bandung Conference in Indonesia, in 1955 – founding year of documenta – a watershed event for post-colonial consciousness, which loudly proclaimed solidarity amongst former colonized countries in Africa and Asia. The latter was introduced through Richard Wright’s The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference (1956), a copy of which was exhibited in a vitrine next to the Marshall plan posters.

7 Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), documenta 14, caption text, also available online: http://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/21956/samuel-beckett. Samuel Beckett also spent time in Kassel, site of his love affair with his cousin Peggy Sinclair, whose portrait by Kassel Secession’s leading painter Karl Leyhausen hung in the room next to the vitrine hosting Beckett’s diary. Beckett’s diary contributed to sketching out the vivacity and openness of the intellectual and artistic circles in Kassel in the 1920s and 1930s, particularly around the Secession, members of which were both Arnold Bode and Leyhausen.

8 Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), documenta 14.

9 On Gurlitt’s activity as a gallerist in Hamburg in 1935-1937, see Meike Hoffmann, Nicola Kuhn, Hitlers Kunsthändler Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895-1956). Die Biographie (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2016), 155-172; on Beckett’s visits at Gurlitt’s, among others for a Max Beckmann exhibition, 167-168.

10 No explicit reference to Gurlitt was made in the accompanying text. On Gurlitt’s arrest by the Monuments Men and his release, see Catherine Hickley, The Munich Art Hoard: Hitler’s Dealer and His Secret Legacy (London: Thames & Hudson: 2015), 105-129.

11 On 6 November 1945, Walter Farmer, the head of the Central Collecting Point Wiesbaden was asked to transport 202 European art works to the USA. Despite his protest that crystallized into the manifest, the paintings were sent overseas and presented in thirteen cities in a touring exhibition. They were only returned in 1948 after further protests by order of the President Harry Truman, who was at the time launching the Marshall Plan. See mainly, Lynn H. Nicholas, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War (New York: A. Knopf, 1994), 389-405.

12 Pieces like The Wiesbaden Manifesto, the so-called Godesberg Program of the Social Democratic Party (1959), economic documents related to the launch of the new German Mark and the highly favourable for German economy London Debt Agreement (1963) cleverly pointed to the developments that marked the political and economic reconstruction of Germany after the war and proposed a telling archaeology of the institutions that still govern over the economic fate of Europe, highlighting a moment when the continent’s great debt offender was not Greece, but Germany.

13 Egon Fleck and Edward Tenenbaum, Buchenwald: A Preliminary Report, 24 April 1945, Library of the Federal Social Court, Kassel, exhibited archival document. On this report and the context of the camp liberation see, Dan Stone, The Liberation of the Camps: The End of the Holocaust and Its Aftermath (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press: 2015), 72-76.

14 On Gurlitt’s activity as a lender in this context, see Matthias Frehner, Muss die Kunstgeschichte des 20.Jahrhunderts neu geschrieben werden? Eine erste kunsthistorische Analyse des Gurlitts-Bestandes, in Kunstmuseum Bern und Kunst-und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland GmbH, ed., Bestandsaufnahme Gurlitt (Bonn, Munich: Hirmer, 2017), 82-85.

15 Cornelia Gurlitt (1890-1919), documenta 14, caption text, also published online, http://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/22738/cornelia-gurlitt.

16 Karl Leyhausen (1899-1931), documenta 14, caption text, also published online, http://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/21980/karl-leyhausen. Bode died in a car accident in 1956.

17 These are evident in other areas of the exhibition, cf. my forthcoming article Courbet at documenta 14: Charity and Other Alternative Economies, in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte.

18 On Schutter’s project, see Keeper of the Art That Kept Him: David Schutter in Conversation with Dieter Roelstraete, http://www.documenta14.de/en/notes-and-works/21168/keeper-of-the-art-that-kept-him.

19 Dawn (Portrait of the Artist’s Father) and Midnight (Portrait of the Artist’s Mother), both dated 1979.

20 “Max Liebermann (1847-1953), documenta 14, caption text, also published online: http://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/21981/max-liebermann. A relief-replica of Max Liebermans’ Two Riders on the Beach (1901) made by American artist Christian Thee for the rightful owner David Toren to which the work was returned, was presented amongst the material of Maria Eichhorn’s project, The Rose Valland Institute, that fully documented the case. Since Toren is blind, the artist replicated the work in the form of a relief. See “I distinguish between Germans old enough to have played a role in the war, and the post-war generation.” Interview with David Toren (2016-17), The Rose Valland Institute, http://www.rosevallandinstitut.org/toren_en.html (accessed 28 March 2018).

21 The Indelible Presence, 95.

22 In her previous major project Restitutionspolitik/Politics of Restitution in Lenbachhaus München in 2003, she tackled issues related to Nazi art theft, in investigating plundered works that became part of the collections of German public museums, as state loans.

23 Rose Valland Institute, http://www.rosevallandinstitut.org/about.html.

24 As the call suggests: “Why do those who have been looted have to attempt to retrieve their possessions, instead of the looters having to locate those robbed in order to return the loot to its rightful owners?”, in “Rose Valland Institute. Open Call: Unlawful Ownership in Germany”, http://www.rosevallandinstitut.org/opencall.html

25 See her comment in the interview, Rose Maria Gropp, Documenta zeigt Maria Eichhorn: Eingetum, das verwaist ist, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Feuilleton, 8 June 2017, http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/kunst/documenta-zeigt-rose-valland-institut-von-maria-eichhorn-15049519.html.

26 It should be noted that the content of the letter is not detailed in the accompanying texts of the exhibition. The letter has been published in: Carta do Rei do Congo, a D. Manuel I (5.10.1514), in Monumenta missionaria Africana 1 (1952), 294-323. See in this regard the exhibition catalogue Kongo: Majesty and Power (New York: Metropolitan Museum, 2015), 89-95.

27 Benin bronzes, Neue Galerie, documenta 14, Caption text also available online http://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/22790/benin-bronzes.

28 See most recently the exemplary provenance research and exhibition of the three Benin bronzes in the collection of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg, Sabine Schulze, Silke Reuther, eds., Raubkunst?: die Bronzen aus Benin im Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (Hamburg: Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, 2018).

29 After a long series of displacements and partial displays of the group, as well as a substantial restoration, the sculptures were seen reunited in 2014 for the first time since the 1920s. Cf. mainly Marianne Heinz, Neue Galerie. Architektur (Petersberg: Michael Imhof, 2011), 20-23; Evelyn Lehmann, Carl Echtermeier (1845–1910). Vergessene Kasseler Künstler, in (K) KulturMagazin: Alles was die Region bewegt, 19/196 (2013), 36-37.

30 Involvement with permanent collections had been rare in the previous iterations. See for instance the way Joseph Kosuth engaged with the works of the collection in this installation Passagen-Werk (documenta-Flânerie) (1992)

31 Benin bronzes.

32 Katalin Ladik, Queen of Sheba (1973/2015), Collage (exhibition copy), sound recording 2:30 min. Collage: MACBA (Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona) Collection, Consortium MACBA, Barcelona.

33 Neue Galerie, documenta 14, http://www.documenta14.de/en/venues/21726/neue-galerie. The group was officially commissioned by the Prussian government as part of a larger iconographical programme of monumental decoration conceived by the architect of the building, Heinrich von Dehn-Rotfelser (1825–1885), cf. Heinz, Neue Galerie, 18-35, 50-58.

34 Destroyed during the Second World War, the paintings are known today only through Merkel’s sketches, see Heinz, Neue Galerie, 28-39.

35 Benin bronzes.

36 Katalin Ladik, Sonata for the DDR Woman Leipzig (1978/2015), Caption text in the exhibition, archive Eleonora Vratskidou.

37 For a list of the works, see Katalin Ladik, documenta 14, http://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13488/katalin-ladik.

38 See the entry of Marta Dziewańska, Katalin Ladik, in Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk, eds., documenta 14: Daybook (Munich, London and New York: Prestel, 2017), unpaginated. On Ladik’s work, see mainly the exhibition catalogue The Power of a Woman: Katalin Ladik Retrospective 1962-2010 (Novi Sad: Museum of Contemporary Art Vojvodina, 2010) and the recent monography by Emese Kürti, Screaming Hole: Poetry, Sound and Action as Intermedia Practice in the Work of Katalin Ladik (Budapest: acb ResearchLab, acb Gallery, 2017).

39 Dziewańska, Katalin Ladik.

40 I am adopting the definition of contrapunctal music by Ralph W. Wood, Modern Counterpoint, in Music & Letters, 13/ 3 (1932), 312. On the significance of the score for the curatorial concept of documenta 14, see Hendrik Folkerts, Keeping Score: Notation, Embodiment, and Liveness, in South as a State of Mind documenta 14 no. 2 (Summer/Spring 2016): 150-169.

41 Benin bronzes. This chronological frame is entirely inaccurate. Although the dating of Benin artefacts is still today extremely problematic, scholars agree that no artefacts can be dated back to the thirteenth century. The closing limit set at the seventeenth century is also absurd since the production of artefacts in Benin was continuous up to the moment of the expedition, when available artefacts in the palace were plundered indistinctively. On the problems of chronology and the political and ideological debates involved, see Stefan Eisenhofer, Höfische Elfenbeinschnitzerei im Reich Benin: Kontinuität oder Kontinuitätspostulat? (Munich: Akad. Verl., 1993). I am grateful to Mr. Eisenhofer for his insightful comments.

42 A large percentage of the Benin artefacts that became available after the British expedition actually came to German institutions, due to a long-standing network of dealers, collectors, institutions and scholars. H. Glenn Penny, Objects of Culture: Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 71-79. As Glenn Penny notes, the intense German interest in Benin artefacts was such that in the 1920s “the Berlin museum alone contained up to eight times as many specimens as the London museum” (p. 9). On the formation of collections of Benin art, see also, Philip J. Dark, An Illustrated Catalogue of Benin Art (Boston, Mass.: Hall, 1982), xiii-xvii.