ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Nathalie Neumann

Research on East Asian objects found in the so-called Gurlitt collection revealed new information about the objects formerly in the stock-in-trade of the dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt, as well as almost forgotten collector’s histories, dealers’ channels and networks on the European market for East Asian art during the decades from 1930 to 1950. While Gurlitt’s main interest lay in Western pictures, there were also a small number of East Asian art objects found in this stock, most of which came from Japan. The objects include ten ceramic bowls and a group of twelve tsuba, but also a bronze sculpture from Thailand and a scroll painting (Kakemono), and eighteen Japanese colour woodcuts. As the focus of this article is on methods, resources, and results of provenance research, a selection of bowls, prints and tsuba was chosen for demonstration purposes, as they are missing individual signs (stamps, seals etc.) which would allow establishing a direct connection to a previous owner. A summary of the research results about all works from Gurlitt’s holdings is continuously updated and available to the public. Even though some questions remain unanswered, the results of the author’s work may lead to increased access and further research of archives in museums, on the art market and on collectors, casting greater light on intertwined relations, which is particularly challenging in the field of provenance research.

With regard to the so-called Gurlitt collection, which was seized in the spring of 2012 at the home of Cornelius Gurlitt (1932-2014), son of the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895-1956), research was concluded after five years of intense work, producing an extensive exhibition catalogue1 as well as four comprehensive publications on the stock-in-trade and biography of Hildebrand Gurlitt.2 Almost, it seemed as if everything was said and done. He was the son of the renowned art historian Cornelius Gurlitt (1850-1938) and trained as an art historian himself. When his career as a museum director ended with the National Socialists’ rise to power, he first ran a gallery in Hamburg before expanding his art market activities, soon becoming one of the most successful dealers on the French art market under Nazi occupation when tasked to act on behalf of the special buying commission “Sonderauftrag Linz” and museums in Germany. At his death in 1956 he left a large stock of about a thousand art works with unknown provenance to his family. The clarification of their provenance was the objective of the research project carried out on behalf of the German Ministry of Culture. A summary of the research results about all works from Gurlitt’s holdings is continuously updated and available to the public on the homepage www.lostart.de, hosted by the German Lost Art Foundation (DZK).3 The author of this article participated in the project as a freelance researcher on European and in particular on East Asian art.

Reflecting his taste and strategies, the stock of the art historian and dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt currently holds several hundreds of prints of so-called “degenerate art”, but also paintings, drawings and prints from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, by German, French, Dutch or Flemish artists. It is perhaps generally less known that there were also a small number of East Asian art objects among them, most of which came from Japan. The stock includes ten ceramic bowls and a group of twelve tsuba, but also a bronze sculpture from Thailand and a scroll painting (Kakemono), and eighteen Japanese colour woodcuts. As the focus of this article is on methods, resources, and results of provenance research, a selection of bowls, prints and tsuba was chosen by the author for demonstration purposes, as they are missing individual signs (stamps, seals etc.) which would allow a direct connection to a previous owner. Even though provenance research is close to the history of collecting, it also must consider the special context of the National Socialist regime legalising the looting of art works in the period from 1933 to 1945. An autopsy of these items will therefore be presented before placing them into the context of collection history.

All objects presented in this article are multiples, i.e. each work may have been produced in several copies. Without individual marking, such as a seal or a stamp, the prior ownership of these works is very difficult to determine clearly, presenting a special challenge for provenance research. However, research in collaboration with specialists made it possible to begin by identifying the objects and the respective artists.4

For two of the ten Oribe-style ceramic bowls (ID 532986, ID 532987) no distinguishing features could be found on the objects. A multi-coloured ceramic bowl (ID 521805) in the shape of a Japanese tea bowl but with fine patterns in Arabic calligraphy points to Islamic culture, but as a mass object produced for export, it could not be clearly assigned to either a group of artists or a previous owner.

Fig. 1: Oribe bowl black, (ID 532990);

© Bundesarchiv Koblenz.

On the bottom of the ceramic tea bowl in black and white glaze (fig. 1) there is the artist’s seal of Kato Shuntai (1802-1877), a Japanese potter from Seto. His real name was Katō Sōshirō, his nickname Nihei, he became known as Shuntai III.5 Already as a 15-year-old, he designed pottery in the Ofuke-yaki ceramic style and executed various techniques, such as red painting, Shino-yaki, and Oribe-yaki. He was a Mugiwarade-style master who used red, white and black motifs before burning. Being one of the last representatives of the local Seto-yaki ceramics “Hongyo”, his seal is a guarantee of a quality brand (figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2: Oribe bowl (ID 532985) ; © Bundesarchiv Koblenz.

The Karatsu-style ceramic bowl (ID 532985 ) in a light tone with speckled glaze bears on the bottom the hand-stamp of the Zōroku family, named after the master potter Mashimizu Zōroku (1822-1877) from Kyoto. But since all members/masters of this family from the fourth generation onward use this seal to this day, the bowl is difficult to date. It is a piece of monochromatic earthenware originally made in Kyoto, but also mass-produced and exported since the nineteenth century.

Fig. 3: Stamped mark Zōroku (ID 532985); © Bundesarchiv Koblenz.

Since ceramic bowls rarely bear owner’s signs, they cannot be easily traced as a single object with or without artist’s signature on the art market or in private collections, especially with regard to the period before 1933. For this reason it seemed helpful to investigate them as a group in context. A photograph of the East Asian ceramic bowls presented a starting point. Signed “Dr. Rumpf” and identifying the bowls on the back, the picture was part of the extensive estate of Hildebrand Gurlitt, which included, in addition to his correspondence, more than 2,000 photographs (fig. 4). 6 At this point, the analysis of the art market in its respective historical context and its actors becomes essential for provenance research in tracing objects, applying the same methods as a collector or a dealer would.

The group photograph of ceramics was used here as a document just as the dealer would have done when offering his articles with a photograph. Consequently, a copy of the original photo was sent to all collections of East Asian art in the German-speaking countries and to museums in Paris, where Hildebrand Gurlitt acquired most of his art works during the German occupation. Unfortunately, no offers or correspondence with Gurlitt on East Asian items have been found in these public collections to date. Even though this result may seem disappointing, the absence of correspondence does not necessarily mean that there was no contact with Gurlitt. This result needs also to be put into historical context. Firstly, dealers would also present their stock in person or through an agent. Secondly, the contents of German archives bear the traces of their historical and political context: gaps are often explained by war losses, whereas after January 1943 (the effective date of the international convention on looting art) archives may also have been “cleansed” of compromising correspondence by persons implicated in looting art so that paperwork would not be traced after the war. Some 80% of actors of cultural institutions and the art market continued in their professional field after 1945.Thirdly, archives in museums do not seem to be a focus of current cultural policies: they are frequently not organised in a modern way, neither digitised nor accessible via up-to-date keywords.7

The analysis of the Gurlitt estate, however, allows to follow the network of experts and traders who Gurlitt also consulted on East Asian art, and who accompanied him to dealers in Paris and elsewhere. One of them was the Japanologist Fritz Rumpf (1888-1949), about whom previous research had found a lack of sources relating to the Nazi period.8 There are two important letters with reference to Fritz Rumpf in the Gurlitt correspondence: on 8 December 1945 he wrote to Gurlitt from Potsdam, enquiring about his health and about the art historian Helmut May,9 as well as drawing a small bronze donkey, which they bought together in Paris in the antiques shop of the Armenian brothers Hagop and Garbis Kalebdjian (fig. 5).10

Fig. 4: Ceramic presentation; © Foto Archive of Gurlitt (file 17.1_F17122_Unbekannt_Keramik_R).

A comparable object can be found today in the collections of the Berlin Ethnological Museum, East and North Asian department, with the provenance: “Mr. Peters of China Bohlken art dealer: Incense Burner, Ming Dynasty, China, bronze, size: h: 17.5 cm, l: 20 cm”.11

Fig. 5: Bronze figure, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum (Ident.No. I D 37247) © SMB.

The second letter is dated January 1943 and sheds light on the relationship between Gurlitt and Erhard Göpel in the power vacuum at “Sonderauftrag Linz” after the death of director Hans Posse (1879-1942) in December 1942 and before the appointment of Hermann Voss (1884-1969) as the new director in February 1943.12 Fritz Rumpf is mentioned as an expert who was to be charged with locating and buying Japanese colour woodcuts for, or in the name of, Gurlitt. Rumpf’s involvement was due to an intervention by the art historian Erhard Göpel (1906-1966).13 However, Rumpf eventually refused this assignment despite – or because – he was at this time probably still in contact with a specialist and dealer on East Asian art, Felix Tikotin (1893-1986) from Dresden, who sought to protect his family and himself as well as his art collection from the persecution by the National Socialists in Holland.14

Göpel and Gurlitt had probably first met at the beginning of the 1930s in Hamburg, where Göpel was a member of the East Asian Society,15 while Hildebrand Gurlitt moved to Hamburg as director of the local art association on 1 May 1931. Here, he presented not only contemporary art, but combined it with one of the finest collections of Japanese colour woodcuts that belonged to the German ambassador in Tokyo, Wilhelm Solf (1862-1936).16 The show proves that apart from modern art, Gurlitt was also interested in non-European art and seems to be well-connected also in this field. 17

Regarding the eighteen colour woodcuts in the Gurlitt stock, they were first examined as individual objects in order to identify artists, motifs and techniques, but also evaluated as a group. The high-quality individual prints give a good overview of the well-known artists of Japanese colour woodcuts of the nineteenth century: Utamaro, Hiroshige, Hokusai and Harunobu etc. 18 Many of the prints are annotated in French with the names of the artists, but none (with one exception) bears an individual collector’s stamp or other signs of prior ownership. For some prints, the historical attribution had to be revised from today’s perspective, but the provenance of the print was researched with reference to both the newly attributed artist and the previous (historical) one. The investigation of the item was supported by research in relevant literature such as exhibition catalogues, monographs, magazines and newspapers. In addition, relevant international databases on looted art were cross-referenced.19 Nevertheless, although the art works discussed here could be clearly identified, no previous owner could be discovered, which is not least due to the fact that the prints are multiples. Three prints formed parts of separate, incomplete diptychs. The respective missing second prints were accordingly searched both in public collections and on the art market.20

Fig. 6: Toyohiro, Daimyo Procession (ID 478518); © Bundesarchiv Koblenz.

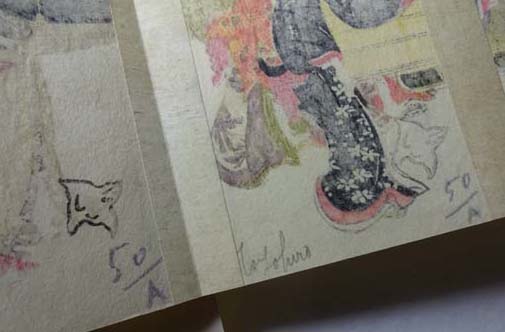

In provenance research on prints, these multiples can only be clearly assigned to a previous owner if they are marked with a collector’s stamp or similar. In the Gurlitt stock there is only one series of seven joined prints that bears a stamp on the back which may be a collector’s stamp. The prints are all signed, except for sheet no.5 which shows only the stamp of the publisher. It is therefore attributed to the Japanese artist Toyohiro Utagawa (1773-1828) and presents a group of fourteen women carrying a sedan chair in their midst, imitating a daimyo procession, in front of a landscape at the foot of Mount Fuji (fig. 6).21

The marginal notes in French on the passe-partout and on the back of the print refer to the artist, “Toyo-hiro”, and next to the note “6 estampes” (6 prints) there are notes about French previous ownership and the transfer of the print in France. Each of the seven prints bears a collector’s stamp on the back. The same mark had been noted by the expert Matthi Forrer in 1983 when he inventoried the high quality and extensive collection of Japanese woodblock prints of the Parisian art dealer Huguette Berès.22 Unfortunately, he could not identify the collector it referred to (fig. 7).23 The stamp shows a stylised bird called plover in English and chidori in Japanese. This Japanese name is also used as a female first name and could point to an as yet unidentified female collector.

Fig. 7: Stamp on back of the print Daimyo Procession by Utagawa Toyohiro. (ID 478518); © Bundesarchiv Koblenz.

For two more colour woodblock prints from the Gurlitt stock it seemed possible to find traces of an owner through the context of their seizure. Both works are signed and provided with a publisher seal, which allowed to attribute them to the Japanese artist Kitagawa Utamaro.24 Like other prints in the Gurlitt collection they are framed mounted with a passe-partout under glass, so that the back of the prints could not yet be assessed. Since the two works were in the possession of Hildebrand Gurlitt by 1946, they were secured by the Allies with other works of art from his collection and taken to the Central Collecting Point Wiesbaden, where an inventory card was created and an initial provenance check executed. However, as the works could not be allocated to a previous owner they were returned to Gurlitt in December 1950.

Apart from the analysis of the Gurlitt estate and his dealer’s network, context research which is the search for collectors of East Asian art and their destiny adds an important third perspective. This applies both to collections of persecuted persons as well as those who benefited from the persecutions. However, it is also necessary to bear in mind that East Asian art and most of all Japanese woodblock prints have been coveted and sold in sets since the late nineteenth century throughout Europe. Among the most important collectors should be considered Julius Kurth (1870-1949), Curt Glaser (1879-1943), William Cohn (1880-1961), Georg Oeder (1846-1931), but also the French collectors Florent Fels (1891-197), and David David-Weill ( 1871-1952), to name just a few. Their collections can be reconstructed partly due to their correspondence with experts, much of which has been preserved in museum archives such as that of the MKG in Hamburg.25

Collector correspondence also became a starting point for research on my last group of art works in the Gurlitt stock, as well as another example of research on art collections: tsuba, that is ornate Japanese sword guards.26 In my search for specialised collections in the archive of the MKG Hamburg, I came across extensive correspondence between the museum staff and the then recognized tsuba collector Martin Kuznitzky (1868-1939?) from Cologne, whose photo archive survived until shortly after the war,27 while he and his large collection disappeared without a trace. Kuznitzky was a German-Jewish urologist and dermatologist and a passionate collector of tsuba. He had applied his thirst for knowledge from medicine and especially microphotography to his collection and photographed and published 37 of tsuba artists’ seals.28 Since the photo archive of Kuznitzky is lost today, no clear connection could be established between his collection and the twelve tsuba remaining in the Gurlitt stock. At the same time, it cannot be excluded that the Kuznitzky collection was looted and subsumed in public and private collections.

For my research on the East Asian art objects in the Gurlitt stock, I used a combination of different methods to investigate every single reference to identify possible previous ownership. In turn, new information about the objects as well as almost forgotten collector’s histories emerged, as well as dealers’ channels and networks on the European market for East Asian art during the highly volatile decades from 1930 to 1950.

Even though some questions remain unanswered, they might lead to increased access and further research of archives in museums, on the art market and on collectors, casting more light on their intertwined relations, which is a particularly challenging aspect in the field of provenance research.

Nathalie Neumann works since November 2017 as a provenance researcher on the art collection of the Federal Republic of Germany (BVA/ Kunstverwaltung).

1 Gurlitt: Status report, edited by Kunstmuseum Bern and Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland GmbH (München: Hirmer Verlag, 2.2018).

2 Meike Hoffmann, Nicola Kuhn, Hitlers Kunsthändler: Hildebrand Gurlitt 1895-1956 (München: C.H.Beck 2016); Catherine Hickley, Gurlitts Schatz: Hitlers Kunsthändler und sein geheimes Erbe (Wien:Czernin Verlag 2016); and Maurice Philip Remy, Der Fall Gurlitt: Die wahre Geschichte über Deutschlands größten Kunstskandal (München: Europaverlag 2017); Oliver Meier, Michael Feller and Stefanie Christ, Der Gurlitt-Komplex: Bern und die Raubkunst (Zürich: Chronos Verlag, 2017).

3 The object ID numbers correspond to those of the project and allow to search the objects online. The image rights lie with the prosecutor of Augsburg and the Federal archives Bundesarchiv Koblenz.

4 My special thanks go to the curator of Museum of Asian Art SMPK Berlin, Dr Alexander Hofmann, who supported my research with his extensive knowledge and network.

5 Turning Point: Oribe and the Arts of Sixteenth-Century Japan (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2003), 200.

6 The estate of Gurlitt has been digitized and is available for local use at the three sites of the Federal Archives of Germany: Koblenz, Berlin and Freiburg.

7 The central archive of the National Museums Berlin are an exception in Germany and are at a par with France where museums have to entrust their archives to the regional or national archives.

8 Hartmut Walravens, Kriegsgefangenschaft in Japan, in: Du verstehst unsere Herzen gut. Fritz Rumpf (1888-1949) im Spannungsfeld der deutsch-japanischen Kulturbeziehungen (Berlin: Japanisch-Deutsches Zentrum and Weinheim: VCH, 1989), 43-70 (also no. 139-142 of the Nachrichten der Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens / Hamburg).

9 Dr Helmut May (1906-1993) was both employed from 1933 at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne and led the Museum in Düren from 1934 to 1936; as part of the the so-called Rhineland gang he was involved in looting art in France and benefited from it on behalf of the Cologne Kunstverein.

10 The antiques shop Kalebdjian Frères was located at 12, rue de la Paix, Paris [later 21, rue Balzac, Paris]. It was suspected after 1945 of collaborating with the German authorities, cf. Archives nationales Paris, F/12/9630, Dossier Garbis Kalebdjian, and thesis by Barbara Schröter, Stoff für Tausend und Ein Jahr: Die Textilsammlung des Generalbauinspektors für die Reichshauptstadt (GBI) Albert Speer (Norderstedt: books on demand 2013), 217ff.

11 Bronze Esel (Ident.Nr.I D 37247, Sammlung: Ethnologisches Museum, SMPK).

12 Göpel’s letter to H. Gurlitt, 15 January 1943 (Finke estate - Düsseldorf, Mahn- und Gedenkstätte). Also available in the Erhard Göpel estate at the Bavarian National Library (manuscripts archive) Munich BSB, Ana 415.

13 Göpel had been ordered to Holland in June 1942 after the Russian campaign, where he was associated to the Reich’s Commissioner for the occupied Netherlands with far-reaching powers and resources for art looting. He had recommended Gurlitt as a dealer for the special mission Linz (“Sonderauftrag Linz”).

14 Extensive correspondence between Tikotin and Rumpf (1923-1949) was kindly made available by the grandson of Tikotin, Jaron Borenstaijn, thanks to Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz. I am grateful to both. On Tikotin, see also Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz’s article in this issue (DOI 10.23690/jams.v2i3.57).

15 Göpel estate, letter to extend his membership at the Ostasiatische Gesellschaft OAG, (East Asian Society).Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (BSB) Munich, Ana 415.

16 Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, Holzschnitte von Kawase Hasui, Die Solf’sche Schenkung im sammlungsgeschichtlichen Kontext, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, no.29 (2015), 30-40.

17 Presumably the exhibition was taken over from the East-Asian Association Hamburg-Bremen whose archives are no longer complete. The objects could not be identified in detail, but a small note by Wilhelm Solf to Gurlitt confirms that it was indeed Solf’s collection, see: Archive of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg: MKG 1909-1955, Miscellaneous 7. Kunstverein.

18 Since the objects were put online following the presentation of the original paper on which this article is based at the conference “Provenienzforschung zu ostasiatischer Kunst” in Berlin in the autumn of 2017, illustrations and brief descriptions are omitted and referenced here at lostart.de: ID 478456 , ID 478455 and ID 478533, as well as ID 478508 to 478522.

19 Lostart, German sales (UB Heidi), fold3, ERR Holocaust.

20 Osaka print master Yoshikuni Jukōdō, ID 478508 , and Toyokuni ID 478516.

21 ID 478518. A comparable version of the same series of prints is in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, but there are two more on the left and one additional on the right.

22 Huguette Bères was the daughter of the antiquarian Pierre Berès (1913-2008), considered the king of the French book trade in the 1930s and 1940s, and owner of a fine rare book collection.

23 Matthi Forrer, collector’s seals, in Andon, no. 12 (1983), 8. ( VIII G 1). I am grateful to Dr Jirka-Schmitz for this information.

24 Utamaro ID 478456 and ID 478455.

25 Even though these collectors could not be presented in the context of this article, their archives were consulted with regard to research about the items from the Gurlitt stock.

26 Gurlitt stock: ID 521817.

27 The photoarchive was mentioned in a letter from director Otto Kümmel (East-Berlin) from 1950 to Peter Meister (MKG Hamburg), but it has disappeared since.

28 See Nathalie Neumann, Martin Kuznitzky - Spurensuche zu einem tsuba-Sammler aus Köln, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift 35 (2018), 37–45.