ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Silke Reuther

The subject of this article are the East Asian objects in the collection of Philipp Fürchtegott Reemtsma (1893–1959), a leading tobacco and cigarette manufacturer based in Hamburg. In 1968, to mark the tenth anniversary of Philipp F. Reemtsma’s death, his widow, Gertrud Reemtsma, produced a catalogue of her late husband’s collection of Chinese objects, which she presented to friends, advisers, and art dealers. Her correspondence shows how well-connected Reemtsma had been as a collector without ever cutting much of a public figure in the art world. As Reemtsma bequeathed a large part of his collection to the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in his hometown, the provenance of these objects subsequently came into focus in the course of the – by now – widespread research initiatives into the history and origins of collections held in public museums in Germany and elsewhere. Reemtsma’s estate is preserved at the Hamburg Institute for Social Research and presented a valuable resource, complemented by auction catalogues and other archival records. While provenance information on the objects now in the Hamburg museum is scarce, the investigation yielded at least some information on a very private collector’s sources, advisers and purchases.

In 1980, when Leopold Reidemeister revisited the Berlin art scene of the 1920s in his article ‘Die Anfänge der Weltkunst und das Berlin der zwanziger Jahre’,1 he described a clientele of collectors where everyone knew everyone else. That group included Philipp Fürchtegott Reemtsma (1893–1959), a leading tobacco and cigarette manufacturer based in Hamburg.

Reidemeister – on the staff of Berlin’s Museum of East Asian Art since 1924 – acted as an adviser to numerous collectors of Far Eastern art. How close he was to them is borne out by his correspondence, which is preserved at the former Prussian state archives (Geheimes Staatsarchiv) in Berlin. He advised and facilitated acquisitions as well as the sale of entire collections and prepared the accompanying auction catalogues. The close-knit nature of this network, which also included Reemtsma, is exemplified by Reidemeister’s relationship with Friedrich Henry Hesse, a Dresden-based collector of East Asian art.2

For Hesse, as for Reemtsma, Reidemeister was the go-to person in all matters relating to their collections. In 1939, when the spectre of the imminent war prompted Hesse to dissolve his collection, it was clear that Reidemeister would compile the catalogue for the auction, which was conducted by Hans W. Lange in 1940. Reemtsma’s acquisition of eight pieces (through a middleman) at that auction can be credited to Reidemeister’s successful networking.3

Fig. 1: Monochrome glass and porcelain from the Reemtsma collection on display at the MKG, photo: Martin Luther/Dirk Fellenberg.

In 1968, to mark the tenth anniversary of Philipp F. Reemtsma’s death, his widow, Gertrud Reemtsma, produced a catalogue of her late husband’s collection of Chinese objects, which she presented to friends, advisers, and art dealers. Her correspondence shows how well-connected Reemtsma had been as a collector without ever cutting much of a public figure in the art world. The fact that in his article of 1980 Reidemeister openly named him as one of the ‘collectors […] of primarily Chinese art, with whom I enjoyed a constant exchange of ideas’ ran counter to Reemtsma’s customary diffidence. To this day, it is impossible to tie any of Reemtsma’s acquisitions to him personally. He invariably bought through his trusted advisers, among them Martin Feddersen, curator of Asian art at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe (MKG) in Hamburg, and the Hamburg art dealer Paula Heuser.

“You can imagine,” Reidemeister wrote to Gertrud Reemtsma in 1970, “that this beautiful book brought back many memories. Many a time your husband and I made our way from the East Asian Museum to pay a visit to the art dealers. But above all, I was delighted to be reminded – and I had forgotten – that Dr Feddersen, acting on behalf of your husband, had bought the best pieces from the collection of my friend Dr Friedrich Hesse at the Lange auction.”4

Fig. 2: Preview of the collection of Friedrich Henry Hesse at Hans W. Lange in Berlin, Bellevuestraße 7, photographer unknown.

The Hesse collection raises no concerns about the legitimacy of its ownership. The provenances of eight pieces in the Reemtsma collection as well as that of seven objects at the MKG could be established and traced back to the Hesse collection. They were acquired by Feddersen who attended the auction on behalf of Reemtsma and the MKG.

We do not know where Reidemeister and Reemtsma’s excursions into the Berlin art trade took them. The business records of leading dealers such as China-Bohlken, Ludwig Glenk, Ernst Fritzsche, or Erna Lissa are lost, so we cannot reconstruct precisely what Reemtsma purchased and from whom. That China-Bohlken must have been a key source is suggested by a letter from Eva Bohlken to Gertrud Reemtsma: ‘We are, of course, particularly interested in your collection, because we still remember the time and the many hours your husband spent with our long-late father in Berlin, so that a sizeable part of your beautiful collection must surely come from our firm.’5 However, this provenance can be considered for just one small porcelain vase. In 1939, China-Bohlken placed an advertisement with a picture of a turquoise bottle vase in the Kunstrundschau. The conspicuous markings of the glaze and the dimensions correspond to those of a vase in the Reemtsma collection. But since this type of vessel was produced in large numbers, the provenance must remain conjectural.

Fig. 3: Chinese snuffbottles from the Reemtsma collection on display at the MKG, photo Martin Luther/Dirk Fellenberg.

Reemtsma first became interested in Asian art in 1934 – according to Martin Feddersen, as a result of a sea voyage to the Far East. In the early 1930s, when Reemtsma commissioned Martin Elsaesser with the design of a luxurious modernist villa in Hamburg Altona, the architect also set his patron on the path to collecting art. Reemtsma turned to the museums in Hamburg and Berlin for advice and support. He did not become an impassioned collector, but merely wanted good art for his home. Over the course of six years, he bought 342 pieces, most of them Chinese, and stopped collecting in 1940.6

The collection of Chinese objects was intended to complement the interior decor of the villa. The fact that the vases and bowls were used means that any trace of their origin – labels, stickers with auction lot numbers etc. – rubbed off over the decades.

Reemtsma’s estate is preserved at the Hamburg Institute for Social Research and accessible to researchers. As the collection of Asian objects was intended for the villa in Hamburg Altona, all the documents pertaining to the construction of the villa in 1930–32, its remodelling in 1938/39 and occupation by British forces from 1945 to 1952 were consulted. The files on the remodelling were the only ones to yield any information. They contain a list recording the acquisition of a Chinese glass collection from Erna Lissa as well as several unspecified purchases from Ernst Fritzsche and China-Bohlken in Berlin and Ludwig Bernheimer and Hugo Meyl in Munich.7

The sizeable sum of 5,000 Reichsmark suggests that all the glass objects of the collection were bought as one lot, but there is no document to back up this assumption – nor is there any record of when Erna Lissa came into possession of the stock. Only a single glass vase can be identified as an unsold lot in the 1926 auction of the Franz Lissa collection. Further research into the art dealers mentioned on the statement produced no results.

When Reemtsma’s villa was requisitioned in November 1945, Wilhelm Scharnberg drew up a valuation of the complete inventory. It makes no mention of the Asian art collection, which had been immured in the cellar in March of that year. However, the correspondence shows that Feddersen had appraised the entire collection in detail in 1940. Unfortunately, there is no trace of his compilation, which may even have included references as to where the individual items had been acquired.

In 1949, Reemtsma asked the British command for his “wife’s Chinese crockery” stored in the cellar of the house. The pieces were handed over to Gertrud Reemtsma on 10 May, and the subject of the collection was not raised again between Reemtsma and the authorities. In 1941, it made a first appearance as a discrete entity in his wealth tax declarations, but its value was a rough estimate. It is reasonable to assume that Reemtsma never submitted Feddersen’s valuation to the fiscal authorities. Thus, his exquisite collection of East Asian works of decorative art mutated into a miscellany of Chinese crockery.8

It was not until 1966, seven years after Reemtsma’s death, that the Hamburg art dealer Hans-Jörgen Heuser drew up another evaluation of the collection. His inventory does not include any provenance information. In 1974, the collection entered the MKG as a permanent loan – transmuted into a gift in 1974 – without any provenance record.

As Reemtsma’s adviser, Martin Feddersen was close to the collector. He attended auctions on his behalf and presumably also purchased objects from dealers. Yet the only visible trace of his work are his annotations on the pages of auction catalogues.

Feddersen kept his museum work and his advisory activity strictly separate. There are no records of his work for Reemtsma at the MKG, and his private papers have not come down to us. After Feddersen’s death in 1964, his private library, which included the annotated auction catalogues, went to the MKG. These catalogues led to the identification of four major collection sales at which Feddersen bought a total of 65 pieces of Asian art for Reemtsma:

Dr Otto Burchard & Co, 1935

Friedrich Henry Hesse, 1940

Johannes Bousset, 1939

Georg Wegener, 1940

After 1937, when Feddersen was forced to leave the museum because of his Jewish wife, he continued to work for Reemtsma and on his publications on Asian art. His richly illustrated handbook Chinesisches Kunstgewerbe (Chinese Decorative Arts) came out in 1939. He did not draw on the Reemtsma collection for images, preferring instead to use pieces in public collections alone. The book contains no provenance information whatsoever.

Feddersen’s disregard for the importance of provenance information is symptomatic of a general deficit. To this day, adequate provenance information is the exception rather than the rule in catalogues of exhibitions or collections of Far Eastern art. If such information is provided at all, it tends to go no further than the name of the previous owner – provided it adds prestige to the object.

Further evidence for the ubiquity of this laissez-faire attitude is provided by a document in the archives of the MKG: In 1932, when Max Sauerlandt, director of the museum, asked the Bremen lawyer, collector and art dealer Johannes Jantzen for the provenance of a piece the latter was offering for sale, he received the answer that there was no provenance because the piece had come up on the art market.

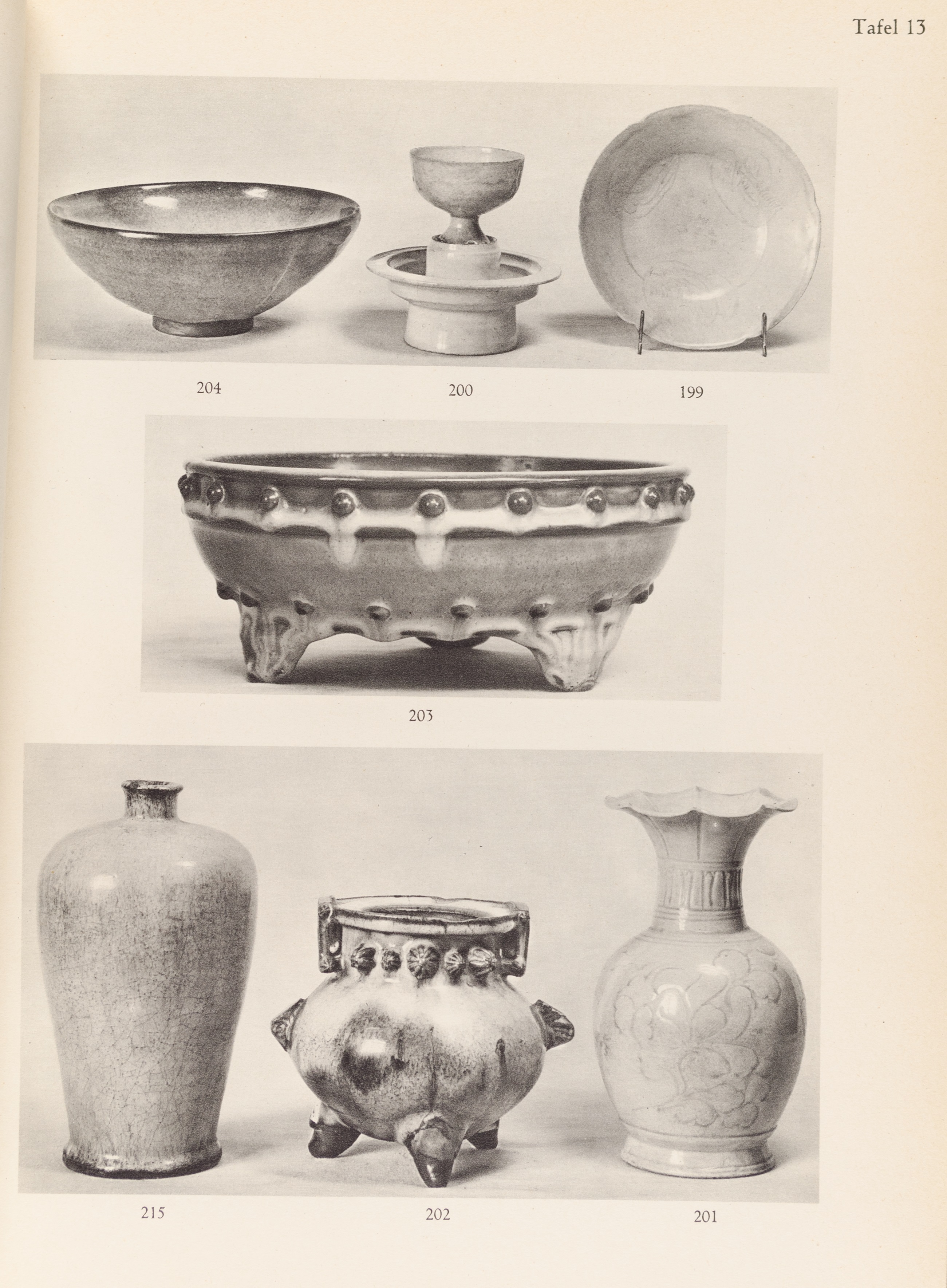

Fig. 4: Illustration from the auction catalogue Sammlung eines Rheinischen Großindustriellen, 1936. The bulb vase, formerly with Dr Otto Burchard, came to the MKG as part of the Reemtsma collection, photographer unknown.

Paula Heuser in Hamburg was another adviser and art dealer who played an important role in the development of Reemtsma’s collection. She was on friendly terms with the family, and several works of art entered the collection through her. Heuser dealt primarily in paintings, but maintained a side-line in Asian objects and decorative arts. Unfortunately, her business records have not come down to us, so that we do not know whether Reemtsma acquired any Far Eastern objects from her.9

Aided by his advisers, Reemtsma covered much of the art market, but cultivated no personal relationships with art dealers outside his circle of advisers. In 1940, the Leipzig art dealer Curt Naubert expressed his indignation at being thus slighted in a letter to Reidemeister: “Today I offered this case with the selfsame description and the selfsame photos to Mr Reemtsma, not to him directly, but to his office, as requested. […] The Chinese silk tapestry fragment was acquired by Mr Reemtsma. It is a pity that he did not let me know whether he was interested in all of Far Eastern art or just in China.”10

Letters such as this – preserved among the files at the Zentralarchiv in Berlin on the Museum of East Asian Art’s holdings – are rare. Naubert never got a chance to establish a closer relationship with Reemtsma, who stopped collecting Far Eastern art later that year.

Reemtsma’s clear-cut period of active buying, which lasted just short of six years, permits a systematic review of relevant specialist publications during this timeframe. The Ostasiatische Zeitschrift does not mention the collector, although he was a member of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst (German East Asian Art Society). Only one provenance could be established on the basis of an auction review in the journal: a bulb bowl, sold into a private collection at the Dr. Otto Burchard & Co. auction in 1935, was bought by Reemtsma in 1936 at the Sammlung eines Rheinischen Grossindustriellen auction. The illustrated piece was identified on the basis of a distinctive drip mark in the glaze.11

The journals Die Kunstauktion, which became Die Weltkunst in 1930, and the Kunstrundschau were searched as well. Once again, there is no mention of Reemtsma. The illustrations of the articles and advertisements provide no leads beyond the known provenances of the dealers Dr Otto Burchard & Co. and China-Bohlken.12 The journal Pantheon yielded an article about the art dealer and collector Alexander von Frey, which is illustrated with an image of a Chinese vase in the Reemtsma collection. Further research showed that the piece had been sold by Von Frey in 1932 to cover debts and that its provenance is thus untainted by Nazi persecution.13

The systematic review of publications also included auction catalogues of the period. Illustrations shed light on the acquisition of a porcelain bowl and two “dragoon” vases, which first came up for auction in 1936 as part of the sale of the Margarete Oppenheim collection. Reemtsma bought the bowl at the auction; the two dragoon vases remained unsold. Reemtsma acquired them – probably the same year – from Weinmüller who auctioned off the remainder of the Oppenheim collection.14 Other acquisitions could be linked to the 1933 Auktion eines Berliner Privatmannes, in which the collection of Hugo von Lustig was sold, and the 1936 auctions of the collections of Joseph Hartl and Friedrich Sarre.15 Over the course of the systematic review, a total of 241 auction catalogues were searched. It became evident that illustrations provide the only viable clue to the identification of the pieces. The investigation established (as far as possible) the provenance of a total of 91 Asian decorative objects in the Reemtsma collection. All the remaining items are registered as Found Object Reports on the Lost Art database.

Silke Reuther is a provenance researcher at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg.

Translated by Carola Kleinstück-Schulman for Büro LS Anderson

1 Die Weltkunst, vol. 50, no. 10 (1980), 1378–1382.

2 Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin: Leopold Reidemeister estate, VI. HA. NLReidemeister, no. 4, 10, 15.

3 Sabine Schulze and Silke Reuther, Raubkunst? Provenienzforschung zu den Sammlungen des MKG (Hamburg: Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, 2014) 118–121.

4 Private Reemtsma family archive, Leopold Reidemeister to Gertrud Reemtsma, letter of 2 January 1970.

5 Private Reemtsma family archive, Eva Bohlken to Getrud Reemtsma, letter of 17 September 1974.

6 Silke Reuther, Die Kunstsammlung Philipp F. Reemtsma. Herkunft und Geschichte (Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 2006) 21–35.

7 Schulze and Reuther (2014), 110.

8 Hamburg Institute for Social Research, Philipp F. Reemtsma estate, PFR 170,04.

9 Reuther (2006), 30–31.

10 Central Archive of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Bestand Ostasiatisches Museum, OAK 12, Curt Naubert to Leopold Reidemeister, letter of 22 February 1940.

11 Schulze and Reuther (2014), 46–47.

12 Ibid., 107.

13 Ibid., 122–125.

14 Ibid., 52–59.

15 Ibid., 126–127.