ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Ilse von zur Mühlen

In 1935, the Bavarian State Ethnological Museum, now Museum Fünf Kontinente in Munich acquired several early Chinese objects at a series of sales held at the Berlin auction house of the Jewish art dealer Paul Graupe. The research results presented in this article are based on the findings that were initially prompted by a restitution claim for these objects. According to the title of the auction catalogue, the circumstances of the forthcoming sale appeared to be the liquidation of the stock of the firm Dr Otto Burchard & Co, Berlin, with Chinese art in catalogue volume I, offered on 22 and 23 March 1935 and a further section catalogued in volume II, offered on 29 April 1935. At the sale, the museum bid successfully on thirty-eight artefacts. In addition, two sculptures were donated to the museum after the Second World War which had been bought at the same sale by third parties. The need for investigation raised questions about the reasons that had prompted the auctions and the liquidation of the firm Dr Otto Burchard in the first place, and about the previous provenance of the Chinese objects. In the wider context of provenance research, the earlier history of the objects also had to be investigated. Extensive research covering museum documentation, a wide range of archival records and the assessment of a highly complex financial situation formed the basis for a new perspective on the potentially contentious circumstances of this acquisition.

This article is based on a paper presented at the Berlin conference “Provenienzforschung zu ostasiatischer Kunst” on 13-14 October 2017. The research was initially prompted by a restitution claim for several early Chinese objects, which had been acquired by the Bavarian State Ethnological Museum, now Museum Fünf Kontinente in Munich, at two sales in the Berlin auction house of the Jewish art dealer Paul Graupe in 1935.

The title of the auction catalogue explained the circumstances of the forthcoming sale. The stock of the firm Dr Otto Burchard & Co, Berlin was to be liquidated, with Chinese art in catalogue volume I, offered on 22 and 23 March 1935 (catalogue no. 140) and a further section catalogued in volume II, offered on 29 April 1935 (catalogue no. 143). From the wording on the catalogue cover, it seemed clear that an art dealing firm was in liquidation and that its stock in trade was being auctioned at Paul Graupe’s. At the two sales, the museum bid successfully on thirty-eight artefacts. In addition, two sculptures were donated to the museum after the Second World War which had been bought at the same sale by third parties.

The need for investigation raised questions about the reasons that had prompted the auctions and the liquidation of the firm Dr Otto Burchard in the first place, and about the previous provenance of the Chinese objects.

The firm Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH2 specialised in antique East Asian and Chinese Art. It was founded in 1926 and was officially registered as a commercial enterprise on 28 October of that year.3 On the same date the firm became part of the Margraf Group, a conglomerate owned by the Jewish entrepreneur Albert Loeske until his death in 1929.4 While Otto Burchard appeared to be co-owner and the business manager of the company Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH, he may have been forced to renounce on his co-ownership already in the beginning of the firms existence.5 In practice, the Margraf Group owner Loeske’s business manager Jakob Oppenheimer seems to have been authorised to conduct most business transactions. Both Burchard and Oppenheimer were also Jewish and thus potentially subject to racial persecution, which was another relevant factor to be considered in the research project analysed in this article.

Over the years, the Margraf firm had expanded to include numerous subsidiaries in the art trade, such as Galerie van Diemen & Co GmbH (a European painting specialist firm), the jewellery dealer Haack & Co GmbH, the firm Dr Burg & Co GmbH – specialising in antique Egyptian art –, Dr Benedict & Co GmbH, Altkunst Antiquitäten GmbH – both specialising in European painting and decorative arts –, Ziesch & Co GmbH (a tapestry manufacture), Van Diemen Maatschappiji Amsterdam, Van Diemen & Co, New York, and Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH as well as its New York branch, Dr Otto Burchard & Co, New York. When Albert Loeske died in 1929, Margraf was an internationally established and reputable dealer in jewellery, decorative arts, fine arts and Asian arts, with ties to the Netherlands, France and the United States. In 1931, the assets of Albert Loeske were estimated at circa 4-10 million pound sterling,6 and the Berlin finance authority assessed the estate value at some 11,050,180 Reichsmark.7 Inevitably, the Nazi-German authorities regarded the Margraf firm as a prime example of international capitalism and exploitative Jewish commerce.

Albert Loeske bequeathed the entire business shares of the Margraf Group to Jakob Oppenheimer and his wife Rosa, while his friend Rosa Beer became the main heiress of most of his other assets. 8 The firm Dr Otto Burchard and Co GmbH thus went to the Oppenheimers.

During the years when he lived in Peking, Otto Burchard9 remained the business manager of the firm until 1931,10 supplying the firm with art directly from the Chinese market.11 However, after Albert Loeske’s death the Margraf group was in difficulties. Whereas Otto Burchard is still listed as the director of the Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH in the firm’s 1930 directory,12 he was substituted by Jakob Oppenheimer at the shareholders’ meeting on 29 September 1931, thus losing influence in the firm bearing his name.13 As a legal dispute ensued within Margraf, it seems clear that Burchard had not been given previous warning. The dispute was only settled by November 1931. Otto Burchard lost the case and gave up any interest in the firm.14 Later he supplied his nephew Wolfgang Burchard with art from the Chinese market. The younger Burchard had subsequently opened his own business at the gallery Burchard Alt-China in Bellevuestrasse 9, Berlin. 15

Meanwhile Jakob Oppenheimer had taken out a loan over one million Reichsmark from the bank Jacquier & Securius from 1929 onwards in order to invest money in the acquisition of artworks of all kinds, mainly from Russian aristocratic collections, taking as read the inheritance dispositions set out in Albert Loeske’s will. However, the family of Loeske’s brother contested the will, and the finance authorities began to assess the expected sum with view to inheritance taxes. As early as on 22 May 1930, a portion of the business shares bequeathed to the Oppenheimers was frozen by the revenue office for the Berlin-Tiergarten district. Between 1931 and 1932, a small portion of the taxes due was paid, but the greater part of the death duties was still the subject of discussions between the Margraf firm and the finance authorities when the National Socialists took over Germany’s government.16

Jakob Oppenheimer had started already in 1929 to liquidate some of the Margraf art firms. The first seizures by the revenue office together with the repayable credit from the bank Jacquier & Securius had made it clear that not all the subsidiary firms would survive in these years of the Great Depression. The firm Haack & Co was closed already in 1929, in the following year Dr Burg & Co was liquidated, in 1931 the New York branch of Dr Otto Burchard & Co, and in April 1932 the New York branch of Van Diemen & Co closed down. Dr Curt Benedict & Co GmbH went into liquidation on 26 August 1933.17 The remainder consisted of the companies Van Diemen & Co GmbH, Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH, and Margraf Antiquitäten (Altkunst) GmbH. They were merged at two addresses in Berlin: for Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH this meant moving from Bellevuestraße 11A to Friedrich-Ebert-Straße 5 in 1930 and then back to Bellevuestraße 6 in 1931, where the firm remained together with Altkunst Antiquitäten GmbH until both firms were liquidated.18

In the meantime, Jakob and Rosa Oppenheimer had fled from Nazi-persecution to France in March 1933. Fortunately, their Jewish son-in-law Ivan Bloch was a Swiss citizen and could act in their name in all business matters and even serve as contact for the finance authorities. In April 1933 Bloch became the new business manager of the Margraf firm.

Ivan Bloch signed a security pledge of property (Sicherungseigentum) on 13 October 1933 for the Margraf companies in order to secure collateral for a repayment of the enormous debt owed to the bank Jacquier & Securius. This pledge agreement constituted a transfer of the business property ownership to safeguard the claims of the bank, which had been due for years and covered virtually all of Margraf’s still existing galleries’ inventory.19 This included the works of art in the Dr Otto Burchardt & Co GmbH.

Once again Ivan Bloch negotiated with the revenue office, which had seized parts of the Margraf assets between 1930 and 1932. But on 2 December 1933 the finance authorities suggested that in order to prevent Jakob Oppenheimer from minimizing the value of the shares, he should not be given the option of voluntary sales (“freihändige Veräusserung”) of the company assets in Germany.20 This meant that just one month after the bank had received the pledge transfer as security, the entire business shares bequeathed to Jakob and Rosa Oppenheimer – with a total value of 1,500,000 Reichsmark – had been seized by the revenue office to cover the outstanding estate tax.21

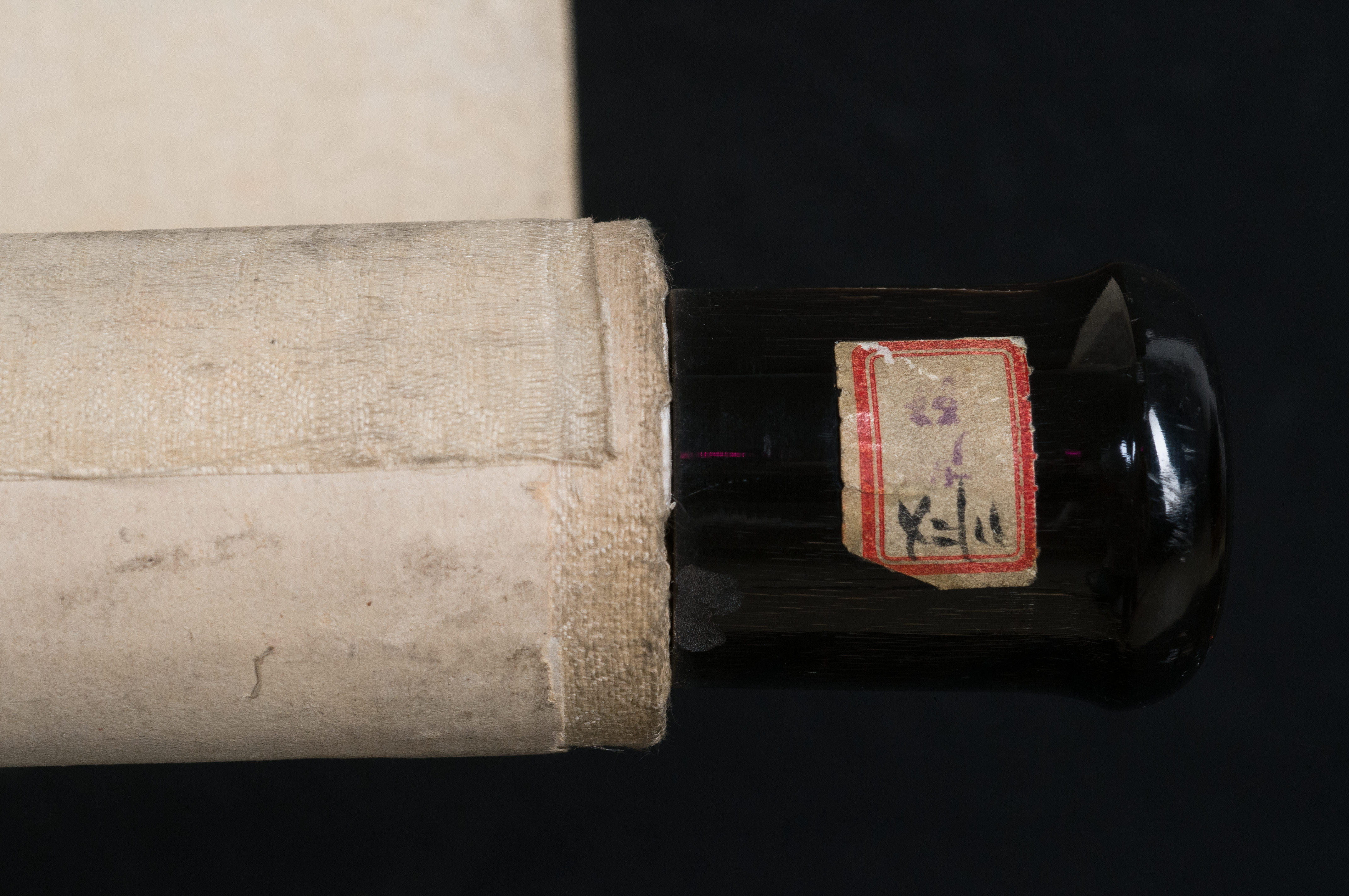

Fig.1: Label from the Chinese customs or dealer of unknown date, found on the Chinese scroll painting with calligraphy, Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.no.35-8-30, © Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marianne Franke.

One year later, the situation of the business had not improved, although Ivan Bloch was still negotiating with the finance authority to minimize the inheritance tax liability. In October 1934, the bank Jacquier & Securius and Ivan Bloch came to an agreement that in order to fulfil loan and debt obligations to the bank (and also to assuage the inheritance tax obligations), three of the Margraf subsidiary limited companies – Galerie van Diemen, Altkunst Antiquitäten and Dr Otto Burchard & Co – would enter liquidation and were to be dissolved (instead, the Margraf jewellery business and Ziesch & Co GmbH continued until 1938). Consequently, on 3 October 1934, Dr Otto Burchard & Co and a few days later Van Diemen & Co and Altkunst Antiquitäten announced their liquidation at the commerce registry. In addition, newspaper announcements were published between 12 and 14 December 1934 which gave official notice of the liquidation of these firms.

On 2 November 1934 a contract was signed between Ivan Bloch as director and liquidator of the Margraf subsidiaries, Paul Graupe as the auctioneer, and the bank Jacquier & Securius as official holder of the consigned property as collateral (Sicherungseigentum). In the details, it determined that Paul Graupe was to set up several auctions, with the objects priced at a limit of 50% of the estimated market value. The bank was to inform Paul Graupe as soon as the debt due to the bank was repaid, with additional proceeds thereafter to be paid to Margraf’s own account.22

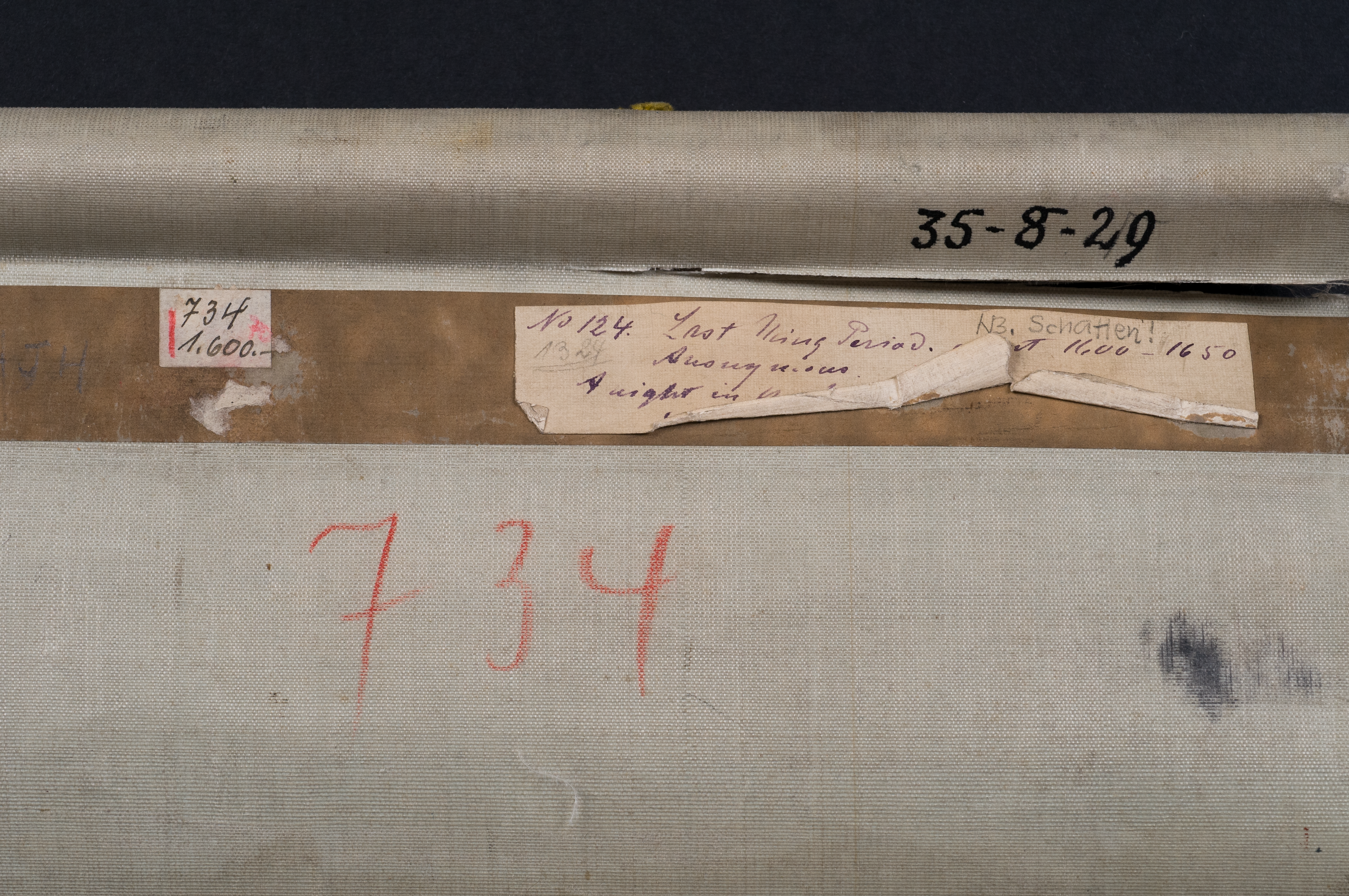

Fig. 2: Price label from the Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH, Berlin, 1920s, found on the Chinese scroll painting with calligraphy. Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.no. 35-8-30 © Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marianne Franke.

As soon as the standard auction conditions of business had been confirmed by the Reichskammer der bildenden Künste, the sales could take place. At this point, the procedure still differed from what were to become the requirements for auction sales after spring 1935, that were dubbed “Jew auctions”.23 It seems that this expression which in itself mirrors Nazi language no longer seems an appropriate terminology for the Margraf sales. They were not organised as a consequence of Nazi persecution, but were the result of a more or less standard business contract among three private partners.

Paul Graupe set up four auctions in autumn 1934, advertised in a special auction brochure24 as well as in all art journals of the time. There were to be three sales of Asian art, the first in January 1935, mixed with European art from Van Diemen and Altkunst,25 and two auctions specially devoted to the liquidation of the Asian art stock of Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH in March and April 1935.26 In the March sale, the Munich ethnological museum (now Museum Fünf Kontinente) was one of the buyers. Fortunately, it preserved its annotated catalogue of the March auction with numerous notes on single pieces, prices and other buyers. Comparisons of the estimates and the auction results for the March 1935 sale could be established on the basis of further annotated auction catalogues from the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg and in the Museum Fünf Kontinente in Munich along with auction results in the Weltkunst Journal. They conveyed a strong sense of the “normalcy” of the auction, with some types of works selling for high prices, and others which may not have been fashionable at the time sold for lesser amounts. The overall total for the March 1935 Burchard sale had been estimated at 154,260 Reichsmark. The total proceeds of the sold lots turned out to be 135,235 Reichsmark. The difference amounts to 19,025 Reichsmark for a total of 597 lot numbers, with just 20 lots remaining unsold.27 This does not suggest either a forced sale or a sale with depressed prices.

Fig. 3: Price label from the Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH, Berlin, 1920s, found on the bronze clasp, Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.no. 35-8-8. © Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marietta Weidner.

The combined proceeds of the sale series came to a grand total of 1,027,343- 1,323,259.33 Reichmark.28 The documentation confirms that the bank received repayment of its credit, with the remainder paid into Margraf’s own accounts.29

In the meantime, Ivan Bloch had reached a deal with the finance authorities. The result was a reduction of the inheritance tax due from originally 4,950,000 Reichsmark (as of 4 March 1930) to only 1,400,000 Reichsmark in 1938. In the meantime, the Chief Finance President had ruled that payment of this sum would be levied from the main heiress Rosa Beer. In addition, she would have to pay 200,000 Reichsmark to the revenue office for the shares in the business which had been seized.30 The remainder of 915,199.92 Reichmark that would have had to be paid by Jakob and Rosa Oppenheimer was ignored, as they had fled to France and were not within reach of the finance authority. 31

To recapitulate, the main objective of the research was to establish if any of the pieces sold at auction were to be returned to the Margraf firm, to the heirs of Jakob and Rosa Oppenheimer, or to Otto Burchard (or his heirs) – or indeed to a third party, as the provenance of each single object may have revealed a seizure in the context of persecution of another Jewish collector, or even a history of having been looted in China, as discussed during the recent Berlin workshop.32 In the following, this article will outline the resources for gathering information about the objects’ whereabouts before their acquisition in 1935. These references were found on the objects themselves, in the documentation in the Museum Fünf Kontinente and in the relevant literature.

Fig. 4: Price label from the Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH, Berlin, 1920s, found on the cup for brushes, stoneware, 13cm high, Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.no. 35-8-25 © Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marietta Weidner.

During the research all objects were inspected in the hope of finding labels or inscriptions that might point to any earlier owner. A few labels found were labels from Chinese dealers or Chinese customs (fig.1). For instance, on the wooden handle of the scroll painting with calligraphy (inv.no. 35-8-30) there is a Chinese white label with a double red lining and handwritten signs, written by a Chinese dealer or Chinese customs, translating as “324”.33

Other labels seem to have come from Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH, as they could be found on almost every object in question. Figures 2-4 show examples of different codes with letters and numbers, which have not yet been decoded. Labels from the Graupe auction appeared mainly on the three scroll paintings (fig. 5). Their numbers match the lot numbers from the Graupe auction catalogue.

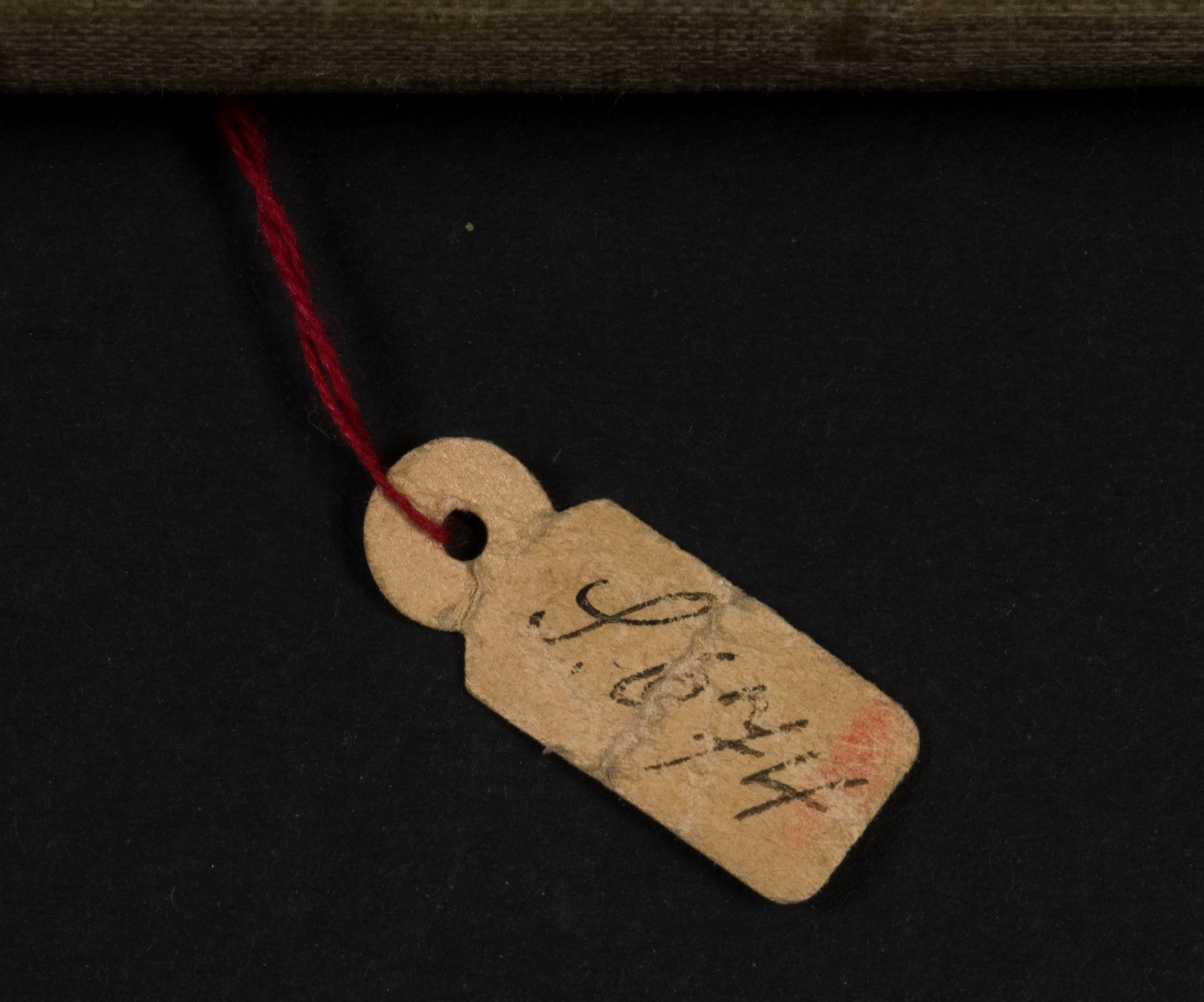

Traces on some of the scroll paintings show that art objects were sent from the Berlin firm to the New York subsidiary. On the Ming period scroll painting, Houseboat at Moonlight, painting on silk, 122x65 cm (inv.nr. 35-8-29, fig. 6) a great deal of information could be found, such as the big label with an ink inscription in English “No. 124 Last Ming Period, about 1600-1650 Anonymous/ A night in the houseboat at moon-light. Cut off on the left side” (fig. 7). The painting was obviously shown in one of the New York exhibitions of Dr Otto Burchard’s stock. Another inscription “734 [and an old price] 1,600” provides old prices and numbers from another, unknown exhibition.

Fig. 5 Paul Graupe auction label, Berlin 1935, found on the Chinese scroll painting with calligraphy, Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.nr.35-8-30

© Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marianne Franke.

For all objects in question, the inventory books and index cards in the museum were consulted. In the case of the acquisitions from the March Paul Graupe auction, some annotations were made in the catalogue during the auction. But with regard to both auctions, the museum was also in contact with staff of Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH in order to gather more information about the pieces which was then added directly into the inventory. In the case of the big Guanyin (Kuan-yin, inv.nr. 35-8-31, fig. 8), the annotation translates as follows: “Herr Burkhardt (in Fa. Dr. Burchard) told me that the figure had been valued earlier at 30,000 Reichsmark. Once it was sent (to an exhibition?) in the United States...”.34 There are two points worth noting here: firstly, the sculpture was already in Germany when high prices could still be expected from potential buyers. However, the price of 30,000 Reichsmark seems to have been too high to attract any client. It is not clear if the label “365 1 Kuan yin Holz [wood] Sung UHGH JGHG” also quoted in the inventory refers to a code for this, or another, earlier price. One could assume that the figure must have been in Berlin already by 1928, when Dr Otto Burchard & Co showed the exhibition of recent Chinese acquisitions.35 Secondly, we also learn from the entry that the art gallery sent objects to the New York subsidiary of Dr Otto Burchard, expecting higher results on the American market.

In the case of the Zun (Tsun, a bronze beaker, inv.no. 35-8-20, from the Zhou (Chou) period the inventory book provides the following information: “Herr Burchard of the firm Dr Burchard told me that the bronze had cost 12,000 Reichsmark a few years ago, and was then reduced first to 7,000 and then to 5,000”. Even though the different prices are not dated, it is obvious that the wonderful piece – it has an inscription on the base (figs. 9-10) – did not find a new owner as the estimate was too high. Probably Dr Otto Burchard & Co also had too many examples on offer. In 1935 there were still six examples in the auction. The estimate for the object in question was lowered again to 1,800 Reichsmark, but in the end it sold at the limit of 50% of the market value (900 Reichsmark).36

Fig. 6: Chinese scroll painting, Houseboat at moonlight, Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), painting on silk, 122 x 65 cm, Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.no. 35-8-29 , © Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marianne Franke.

Fig. 7: Label from Dr Otto Burchard & Co New York (no. 124) and price label from unknown date found on the Chinese scroll painting, Houseboat at moonlight, Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.no. 35-8-29, © Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marianne Franke.

At the beginning of the research process it became clear that one vase had been in another auction before 1935 (inv. no. 35-8-24). It was identified in the auction catalogue of the Munich Gallery of Hugo Helbing on 23 and 24 October 1928.37 Thanks to the annotated auction catalogue in the library of the Zurich Kunsthaus, the name of the seller is known. The initial assumption had been that the firm of Dr Otto Burchard & Co bought some of its stock on the German art market. Surprisingly, the consignor at the Munich auction turned out to be the firm of Dr Otto Burchard & Co, or perhaps Dr Otto Burchard himself (the catalogue entry is not clear in this respect). The price limit in 1928 was “180/185” Reichsmark, but the vase remained unsold and was duly returned to the firm Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH.38 In an additional piece of information, the inventory also cites an earlier price of “800,-”, but it remains uncertain from which date. The impression given by the information in the museum’s inventory is thus substantiated by the history of the vase: in the years from 1928 to 1935 higher prices were no longer realistic, as the Great Depression affected the whole art market from 1929. In the case of the vase however another reason may have played a part: some clients in 1928 already may have come to the conclusion that this vase was probably a forgery.39

Concerns that more forgeries may be identified among the group of objects acquired at the Graupe auctions prompted some RFA-Tests and also several X-Ray examinations.40 The results confirmed however that some of the bronze objects must at least have remained in the earth for a long period. Consequently, the circumstances of excavations made in the early twentieth century needed to be considered.

Fig. 8: Guanyin (Kuan-yin), late Liao- or Yuan

period (twelfth to thirteenth century), wood,

partially painted with traces of gold,

210 x 75 x 50 cm, Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.no. 35-8-31 , © Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marianne Franke.

For the bronze Zhou (Chou) period (1122-255 BC) Taotie (T’ao-t’ieh) mask (inv.no. 35-8-3; fig. 11)41 the following entry can be found in the inventory book: “Karlbeck: found in 1929. ‘From a tomb situated close to Ku-Wei-tsun, which is four Li from Wei-tsien-ch’eng, in the province of Honan north of the Huang-Ho. From a Mound of 6000 qm, 12 m deep. Wooden beams ... and 12 bronze masks. Sandy ground. Mounts from the wooden beams. Period: 3rd Cent. BC.’ Our piece must be from this group. Herr Oeder told me, that they found 19 of them, with 6 or 7 in Stockholm, 2 in Berl[in]. Mus[eum]., 2 he has himself, 1 a Herr Hasse in Bremen. As Oeder reported to Karlbeck, he may not have remembered the number exactly, and Karlbeck’s number will be right. Since 6+2+2+1 and now ours come to 12”.

Accordingly, when the bronze fitting in form of a mask arrived in Munich, the curators were already quite certain that the piece had been found in excavations from a grave in Guweicun (Ku-wei-ts’un). In this case the RFA-Test could verify the old entry, and excavation descriptions were consulted. As Orvar Karlbeck had published his excavations in 1931,42 he must have been the best source for information in 1935, even if it was reported second-hand by the collector Oeder. Very similar objects however have also been found in graves in Luoyang (Lo-Yang).43 For a final verification identifying the correct excavation site one could compare the RFA analysis of the mask with other excavations from Guweicun (Ku-wei-ts’un) in the museums in Stockholm and Berlin. In his article Karlbeck also mentions that the masks were fixed to huge wooden segments of the grave construction. If the nails affixing them were made of iron this could explain the iron identified by the RFA analysis. Again, a comparison with other Taotie (tao-t’ieh) masks in the corresponding collections could help to clarify this part of the story.

Fig. 9: Zun (Tsun), late 11th–early 10th century BC, Zhou Dynasty (Chou period) (1122-255 BC), bronze, height 24,5 cm

Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.no. 35-8-20 , © Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marietta Weidner.

Since 1927 Otto Burchard was living in Peking and therefore would have been close to all sources of information about new excavations. Until 1932 however, he travelled twice a year to Berlin in order to bring new stock to the gallery. In his review of one of the exhibitions at the gallery Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH the art critic Walter Bondy commented: “Dr. Burchard, who buys all his stock in China, only shows pieces we have almost never seen before in Europe”.44 Some of the bronze clasps and other bronze objects, like the part of a wheel hub (inv.nr.35-8-5, fig. 12), must have come from excavations as well. The wheel hub shows similarities to findings from the graves in Luoyang (Lo-Yang).45

With the exception of the examples which came from Chinese excavations and some forgeries the earlier history of each single object is still unknown. For the statues (see fig. 8), research into their previous provenance is ongoing.

The question regarding the whereabouts of these objects immediately before 1933 could be answered to some extent, either through the references to earlier prices or because an object came from an excavation in China and was imported by Otto Burchard himself. With regard to all cited examples it is probable or even obvious that they had been in the possession of the firm Dr Otto Burchard & Co for several years prior to the auction. In the case of the objects which were sent to the United States, they must have been in the possession of the gallery before 1931, when the New York branch of Dr Otto Burchard & Co had to close. 46 As Otto Burchard had lost managerial influence on the gallery bearing his name after the legal case he lost to Jakob Oppenheimer and the Margraf company, it seems likely that he also lost possession of individual objects in the gallery stock.

From the above-mentioned examples it seems clear that from 1928 high prices were no longer sustainable and had to come down. As for the question whether prices achieved in 1935 should be considered as a basis for calculating “fire sale” losses (Verschleuderungsschaden), it could be demonstrated that even before 1933 the prices were set too high for the objects to be sold. During the auction however it was neither in the interest of the bank Jacquier & Securius nor of the auctioneer Paul Graupe to bring the hammer down at results below value. On the contrary, Paul Graupe stuck to his deal and finished the auctions with a total well above the 50% of market value that had been set as a limit in the contract. The examples from the Museum Fünf Kontinente that are the subject of this article do not provide information on the issues of co-ownership of high value pieces, which was common practice among dealers. It is also not clear whether the acquisitions of the Museum Fünf Kontinente included pieces sold on a commission basis. Under the terms of the contract these would have been excluded from payments to the bank, and Ivan Bloch would have paid most of the proceeds to the (today) unknown vendor.

Fig. 10: Zun (Tsun), late 11th–early 10th century BC, Zhou Dynasty (Chou period) (1122-255 BC), bronze, hight 24,5 cm

Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.nr. 35-8-20

© Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marietta Weidner.

As research in this matter has shown, what has been referred to in this case as the Graupe auctions should no longer be included in the terminology of so-called “Jew auctions”, as the reasons for the liquidation were rooted in the period before 1933 and in the financial difficulties created out of demands for inheritance taxes and the repayment of enormous debts.47 Furthermore, neither the finance authorities nor other Nazi authorities (unless they were buyers) were involved in the auctions.

Fig. 11: Taotie (T‘ao-t’ieh) Mask, Zhou Dynasty (Chou period) (1122-255 BC), bronze, greenish patina, partly encrusted, broken, 10 x 11,5 cm, Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.no. 35-8-3

© Museum Fünf Kontinente, Regina Stumbaum

However: the introduction of the “Nuremberg” racial laws in September 1935 greatly exacerbated the persecution measures against people of Jewish descent in Germany. The actions from 1937/38 brought about unmitigated plunder and finally murder of those who were unable to emigrate. The Jewish persons this article refers to were also among the victims. Jakob Oppenheimer died after detention in Nice, Rosa Oppenheimer was murdered in Auschwitz in 1943, Rosa Beer was declared dead in 1942 after having been deported to Theresienstadt. Ivan Bloch, Otto Burchard and Paul Graupe survived in exile. After 1945, Burchard and Graupe managed to return to, respectively continue in, their profession in the art trade.

Another focus not yet considered in the research to date concerns a later sale at Achenbach’s auction house, which also included some Asian art objects from the firm Dr Otto Burchard & Co.48 As circumstances changed during the years after 1935, this area still needs to be investigated.

Fig. 12: Wheel hub, Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.), made of gold and silver tausia with embedded bone, length 18,2 cm, Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, inv.no. 35-8-5

© Museum Fünf Kontinente, Marietta Weidner.

Coming back to the central issue at stake: let us imagine that an object taken during the attack on the Chinese imperial summer palace somehow reached the Berlin art market, to be absorbed in the stock of Dr Otto Burchard & Co or one of the other art dealers. The object may then have been bought by a Jewish collector, who could have lost it due to National Socialist persecution, leading to another sale of the object in Germany after 1933 where it could have been purchased by a museum. Of course there were a large number of such forced sales at auction, which have been the subject of research over the last decades. Yet the salient point may rather be the frequent presence of Asian art in a large number of mixed art collections at the time. For example, Asian objects were part of the Emma Budge collection, which has been the subject of several restitutions as the result of research into the circumstances of a change in ownership under the Nazi government.49 Asian Art can be identified in auctions arranged on behalf of the finance authorities, as for instance at the auctioneer Pongs in Düsseldorf in 1939. In this case, the Asian art catalogued under lot numbers 320 to 352 belonged to Jewish owners but were being sold by the Düsseldorf finance authorities.50

Bearing in mind the complex history of such objects, provenance research and restitution considerations are likely to become ever more complex in future, as demonstrated by the contributions in this journal issue.

Ilse von zur Mühlen is an art historian and provenance researcher.

1 Research on the circumstances of the 1935 Graupe auctions, as well as the liquidation of the Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH and its mother firm, the Margraf Group, was undertaken in close cooperation with Silke Reuther of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg, together with Laurie Stein, then acting for various American and British museums.

2 On the Berlin Asian art trade in the early 1920s, see also the article by Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz in this issue (DOI 10.23690/jams.v2i4.57).

3 Landesarchiv Berlin (LAB), formerly Amtsgericht Charlottenburg , A Rep.342-02 Nr. 19720, Dr Otto Burchard & Co, fol. 1, application dated 28 October 1926.

4 LAB, formerly Amtsgericht Charlottenburg, A Rep.342-02 Nr. 19720, Dr Otto Burchard & Co, fol. 2 ff, no. 326 notary register of 1926, 25 October 1926. Fol. 26 ff. no. 328 notary register of 1926, partnership agreement dated 28 October 1926.

5 LAB, formerly Amtsgericht Charlottenburg, A Rep.342-02 no. 19720, Dr Otto Burchard & Co, fol. 2-4. 1933; Burchard took Jakob Oppenheimer, the business manager of the Margraf firm, to court.

6 http://newspaper.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/2358651, Canberra Times, 21 January 1931.

7 Archive of the Bundesamt für zentrale Dienste und offene Vermögensfragen (BADV), 2 WGA 3503/50, fol. 103 ff, draft tax demand, 18 November 1932.

8 The original last will of Albert Loeske can be found at the district court of Berlin Mitte, Az. 186. IV 1188/29. An official copy is in LAB, A Rep. 342-02, Nr. 23000, van Diemen & Co.

9 See Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz’s article in this issue, 8-10.

10 LAB, formerly Amtsgericht Charlottenburg, A Rep.342-02 Nr. 19720, Dr Otto Burchard & Co, fol. 18, Note to the district court Berlin Mitte dated 29 September 1931, fol. 19, protocol of the decisions taken at the shareholder meeting on 29 September 1931.

11 Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz: Otto Burchard (1892-1965). Vom Finanz-Dada zum Grandseigneur des Pekinger Kunsthandels, in: Mitteilungen der deutschen Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst, no. 12 (1995), 23-35, here 29.

12 District court Berlin Mitte, probate court, file of the Last Will of Albert Loeske ref. 186.IV.1188/29, fol. 67.

13 LAB, formerly district court Charlottenburg, A Rep.342-02 no. 19720, Dr Otto Burchard & Co, fol. 17.

14 LAB, formerly district court Charlottenburg, A Rep.342-02 no. 19720, Dr Otto Burchard & Co, fol. 39. Ruling in the matter of the commercial register for the firm Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH in Berlin of 10 November 1931.

15 See Museum Fünf Kontinente, München, Collection Schriftgut Altregistratur, file SG-49, fol. 45.

16 See BADV, 3097, audit file Margraf & Co, Zentralfinanzamt. See also Landesamt für Bürger- und Ordnungsangelegenheiten, Berlin (LABO) 40159, Willi Schulz to Berlin Compensation Authority (Entschädigungsamt), 25 June 1956. For Russian acquisitions, see also Anja Heuss, Stalins Auktionen in Berlin, in Sediment. Mitteilungen zur Geschichte des Kunsthandels, no. 2 (1997), 85-94.

17 Reference as per the database of Jewish commercial enterprises in Berlin 1930-1945, compiled by Christoph Kreutzmüller at the Landesarchiv Berlin, based on the Central Commercial Register of the Deutscher Reichsanzeiger und Preußischen Staatsanzeiger, vol. 222 of 23 September 1935, 1. In New York, Van Diemen was eventually taken over by Dr Karl Lilienfeld and continued to trade as the Van Diemen-Lilienfeld Gallery until the early 1960s (http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/guides_bibliographies/provenance/dealer_archives.html, accessed 23 July 2018).

18 LAB, formerly district court Charlottenburg, A Rep.342-02 no. 19720, Dr Otto Burchard & Co, fol. 43ff.

19 BADV, 2367, Audit File Jacquier & Securius, 30 August 1938, 26ff.

20 See Willi Schulz on behalf of the Estate of Rosa Beer, see BADV, restitution file 62WGA 3345/55, fol. 61.

21 The shares of the subsidiary firms, such as Dr Otto Burchard and Co GmbH, seem to have been affected as they were part of the Margraf shares.

22 BADV, 3097, audit file Margraf & Co, Profit and Income Tax Report 1933-36, Von Frankenberg, 26 July 1936, attachment 1, “Paul Graupe Contract, 2 November 1934”.

23 See the definition on the website of the exhibition in the Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin “Legalisierter Raub. Der Fiskus und die Ausplünderung der Juden in Hessen und Berlin 1933-1945”, 2005, see the glossary http://www.dhm.de/archiv/ausstellungen/legalisierter-raub/glossar.html#top (last accessed 11 June 2018).

24 Paul Graupe, auction brochure entitled: Die gesamten Bestände der in Liquidation getretenen Firmen Galerie van Diemen & Co, GmbH, Berlin, Gemälde alter Meister; Altkunst GmbH, Berlin, Antiquitäten, alte Graphik; Dr Otto Burchard GmbH & Co, Berlin, ostasiatische Kunstwerke; ... eine kleine Auswahl bemerkenswerter Kunstgegenstände aus den gesamten Beständen ..., Berlin 1934.

25 Auction Catalogue Paul Graupe, Die Bestände der Berliner Firmen Galerie van Diemen & Co GmbH, Altkunst Antiquitäten GmbH, Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH: sämtlich in Liquidation; Versteigerung ... am 25. und 26. Januar 1935 (I. Teil) (catalogue no. 137), Berlin 1935.

26 Auction Catalogue Paul Graupe, edited by Leopold Reidemeister, Die Bestände der Firma Dr. Otto Burchard & Co, Berlin in Liquidation: chinesische Kunst (Band 1): Versteigerung ... am 22. u. 23. März 1935 (Katalog Nr. 140), Berlin 1935; Auction Catalogue Paul Graupe, edited by Leopold Reidemeister, Die Bestände der Firma Dr. Otto Burchard & Co, Berlin in Liquidation: chinesische Kunst (Band 2): Versteigerung ... am 29. April 1935 (catalogue no. 143), Berlin 1935.

27 Based on the calculation by Silke Reuther, Hamburg.

28 BADV, 3097, audit file Margraf & Co, auditors‘ list.

29 LAB, B Rep. 024-07 (73 WGA 2192.51), pag. 250, Dr. Walter Schwarz to the county court Berlin, 31 January 1958 attachment 2, debit balance of the account statements of Jacquier & Securius, as well as daily debit account statements, unnumbered and included in the same file. For the remainder of the repayments to the Margraf accounts see BADV 2367, audit file Jacquier & Securius, auditor’s report by Obersteuerinspektor Bernott about the audit conducted during the period from 4 to 19 August: “Der Mehrerlös floß Margraf zu” (the excess proceeds passed to Margraf).

30 The sum of 4,950,000 Reichsmark was based on the tax demand dated 4 March 1930, see BADV, restitution file 2 WGA 3503/50, fol. 103 ff., Draft tax demand dated 18 November 1932. The calculation from 1932 increased by 300,000 Reichmark in comparison with the earlier one, which is quoted in the document. The tax demand dated 27 January 1933 reflects once again a reduction of almost 300,000 Reichsmark compared with the tax demand of 27 November 1932, renewing the demand of 4 March 1930. For 1933 see BADV, 3097, audit file Margraf & Co., Zentralfinanzamt, Abschrift vom 24.8.1933. A copy of the decision by the Oberfinanzpräsident Berlin dated 7 May 1938 can be accessed in “Dossier Bloch”, Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv Bern, BAR “Dossier Bloch”, no. 42. I am grateful to Andreas Bernhard of Stadtmuseum Berlin for bringing the Swiss archival material to my attention.

31 BADV, 3067, audit file Margraf & Co, auditor’s report of inspector Finger dated 4 August 1940, fol. 3 of the accompanying commentary for the audit instructions on file.

32 See also Christine Howald/Léa Saint-Raymond, Tracking Dispersal: Auction Sales from the Yuanmingyuan Loot in Paris in the 1860s, in: Journal for Art Market Studies, vol. 2, no 2 (2018), DOI 10.23690/jams.v2i2.30.

33 Kindly translated by Dr. Bruno Richtsfeld, Museum Fünf Kontinente. For the auction catalogue Paul Graupe Berlin, Die Bestände der Firma Dr. Otto Burchard & Co, Berlin in Liquidation: chinesische Kunst (vol. 2): Versteigerung ... am 29. April 1935 (catalogue number 143), of no. 1346.

34 Museum Fünf Kontinente, Inventory book, under inv.nr. 35-8-31. The entries in the inventory are in German with English inserts. They are quoted here in translation. The original text can be found under each inventory number.

35 See the article by Jirka Schmitz in this issue as well as Leonhard Adam, Neuerwerbungen aus China, in Cicerone, vol. 20, no. 5 (1928), 167-170.

36 Auction catalogue Paul Graupe Berlin, Die Bestände der Firma Dr. Otto Burchard & Co, Berlin in Liquidation: chinesische Kunst (vol. 2): Versteigerung ... am 29. April 1935 (catalogue no. 143), Berlin 1935, lot no. 1127, fig. 10.

37 Porzellane / Fayencen / Waffen / Ostasiatika / Metallarbeiten / Möbel / Teppiche / Plastik / Alte Gemälde aus verschiedenem Privatbesitz u.a.B. Versteigerung in der Galerie Hugo Helbing, München. 23 und 24. Oktober 1928 (München: Helbing, 1928), no. 372 with illustration plate 7.

38 I am very grateful to Mr. Rosemann from the library at Kunsthaus Zurich for their pages of the annotated catalogue.

39 This is the opinion of Dr. Bruno Richtsfeld, curator in the Museum Fünf Kontinente. The estimate in 1935 was 60 Reichsmark. At the 1935 auction, the vase was sold for 80 Reichsmark. See auction catalogue Paul Graupe Berlin (as in fn. 36), catalogue no. 143, lot no. 892.

40 I am grateful to the staff at the Archäologische Staatssammlung München for their assistance.

41 Catalogued as with a greenish patina, partly encrusted, broken, 10x11,5 cm. Auction catalogue Paul Graupe, ed. Leopold Reidemeister, Die Bestände der Firma Dr. Otto Burchard & Co, Berlin in Liquidation: chinesische Kunst (vol. 1): Versteigerung ... am 22. u. 23. März 1935 (catalogue no. 140), Berlin 1935, lot no. 289, fig. 29.

42 Oskar Karlbeck, Notes on the Archaeology of China. A Honan Grave Find, in Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities Stockholm, no. 2 (Stockholm 1930, printed 1931), 201-204 with fig. 2, 202, and plate VIII and VI, on the right.

43 William Charles White, Tombs of Old Lo-Yang, Shanghai 1934, pl. XXXIX, 105, XL, 103, XCIV, a.c.d. and description, 82.

44 Die Kunstauktion, vol. 2, no. 5 of 29 January 1928, 3.

45 Han-period, 206 BC - 220 AD, made of gold and silver tausia with embedded bone, length 18,2 cm. William Charles White, Tombs of Old Lo-Yang, pl. VI, 013 a und b, 61.

46 BADV, audit report Margraf & Co GmbH no. 3097 (formerly Reichsnummer 3118). Report of the auditor dated 17 June 1932, auditor Riepl, 2.

47 See https://www.museum-fuenf-kontinente.de/forschung/forschungsprojekte.html and https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/460812/51132_HC440_Cagnes_Report_Accessible.pdf (last accessed 18 June 2018).

48 Auction catalogue Dr. Walther Achenbach Berlin, Die Restbestände der Firmen: Galerie van Diemen & Co GmbH in Liqu., Dr Otto Burchardt & Co GmbH in Liqu.: 13. Oktober 1937 (Berlin, 1937).

49 Auction catalogues Paul Graupe Berlin, Die Sammlung Frau Emma Budge Hamburg: Gemälde, Farbstiche, Skulpturen, Statuetten, Kunstgewerbe. Versteigerung am 27., 28. und 29. September 1937 (Berlin, 1937) and Hans W. Lange Berlin, Verschiedener deutscher Kunstbesitz: Gemälde alter und neuerer Meister (zum größten Teil aus Sammlung Budge, Hamburg), Plastik, Bronzen, Möbel, Tapisserien, Textilien, Silber, Porzellan, Majoliken, Fayencen ; Versteigerung am 6. und 7. Dezember 1937 (Berlin, 1937).

50 Auction catalogue Carl Eugen Pongs, Kunstversteigerer Düsseldorf, Gemälde alter und moderner Meister, Orientteppiche, Möbel, Kunstgewerbe, Silber: Versteigerung 23. bis 25. März 1939 (catalogue no. 8), (Düsseldorf, 1939).